Disinformation: emergency or false problem?

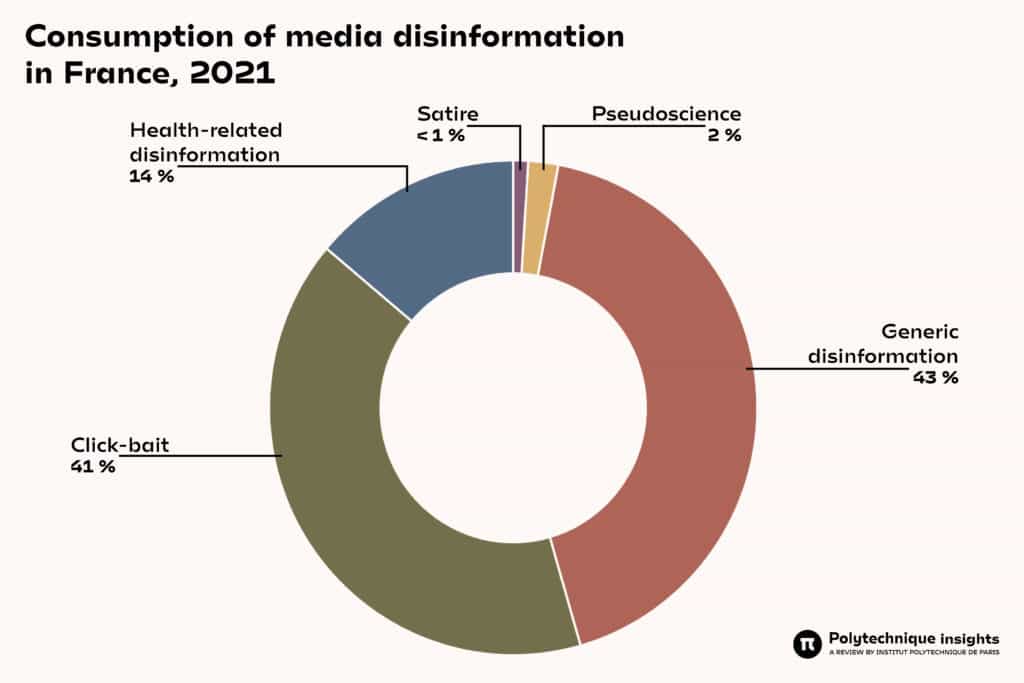

- Currently, it is estimated that the consumption of fake news varies between 0.6% and 7% depending on the country.

- But this only takes into account one type of disinformation, of which there are three main definitions: the factual aspect, the psychological impact and the informational exposure of the general public.

- This latter involves problems such as mute news, which obscures key issues from media attention or flooding where the media is swamped with unreliable information.

- An effective counter-measure is to increase the general population's interest in reliable information, which involves more trust in the media.

“You are Fake News.” These words, uttered by former US President Donald Trump, illustrate the extent to which the problem of disinformation runs through society. Despite his rhetorical use of the term, disinformation is considered a real phenomenon of concern to political authorities. At worst, it can be responsible for moral panic1 where causes of current problems are attributed to disinformation.

Let’s remember, though, that the phenomenon of disinformation is as old as human society. Indeed, ancient myths or the famous propaganda of the 20th Century can be rightly considered as disinformation. The only radical changes are the channels of communication and the possibilities of dissemination. “The Internet has changed the way humans communicate. So, there are new forms of disinformation that have emerged, although disinformation itself is not a new phenomenon,” argues Sacha Altay, a post-doctoral researcher at Oxford University and a doctor in experimental psychology, who specialises in issues of disinformation and trust in the media.

Defining disinformation

Do these new forms of disinformation deserve all the attention they get? Indeed, in addition to the political body, many scientists have become interested in the phenomenon, too. Notably, the aim is to prevent dissemination of disinformation or to prevent people from adhering to erroneous information by developing psychological techniques to try to counter its effect2. However, it remains difficult to say if it deserves so much attention.

In order to do so, we must first look at the definition of disinformation. There are three main definitions: the first focuses on the factual aspect. In other words, is the information true or false? The second focuses on the psychological impact: does the information lead to a biased view of reality in individuals? Finally, the last one suggests focusing on the informational exposure of the general public; this definition is broader and includes information that is factual, but which takes the place of more important information.

Currently, it is estimated that the consumption of fake news ranges from 0.6 to 7% depending on the country.

The factual definition has the advantage of being simple to identify and study. It allows for easy collection of quantitative data on the prevalence of fake news, its consumption and how it circulates. Currently, it is estimated that the consumption of fake news in this sense varies between 0.6% and 7% depending on the country3.

In this sense, however, it is questionable whether fake news is a problem. For Lê Nguyên Hoang, a doctor of mathematics, science communicator and co-creator of the Tournesol algorithm, this is not the case. “Radically false information or information that alters people’s vision is not the core of the problem. In my opinion, it is more on the side of the third definition, i.e. disinformation campaigns organised to highlight certain information rather than others, the harassment of journalists, the creation of false accounts to amplify certain content, the setting up of false debates, etc.” The researcher attests to this with a scientific report documenting the various methods of digital and transnational repression of information4.

Identifying the source of the problem

For Sacha Altay, the most prominent problem seems to be people’s lack of interest in information and politics in general. “Most people and some sections of the population, such as young people from working-class backgrounds, do not care about disinformation. They don’t follow news and politics very much. We really must keep that in mind. One of the major objectives is not so much to increase vigilance as it is to raise interest and restore trust in reliable information.”

Furthermore, a strong argument to put the problem of false information into perspective is that there is no consistent link between the consumption of articles, and the attitude of individuals or their behaviour. This is well known in psychology literature, and US behavioural scientists have stated this in black and white in a report aimed at promoting actions to the public6.

“Simply explaining the scientific findings about covid-19 and the associated risks will very rarely lead to a change in attitudes and behaviours, even if people understand and accept the facts, and even if they report that they should behave differently given the new information,” he says. The main reasons why people do not adopt certain behaviours when they know they should are due to cognitive preferences for old habits, forgetfulness, small inconveniences in the present moment, preferences for what requires the least effort, and motivated reasoning.

Yet, ultimately, this is what the political body wants to do, as is the case with critical thinking education: reduce false beliefs, improve safety, promote public health, etc. Tackling disinformation might therefore be a red herring, as we do not always consume information to satisfy epistemic goals. Sacha Altay gives us a concrete example to illustrate this point, “in the US, people who consume pro-Trump information are pro-Trump. The articles serve more to justify a kind of attitude they already had towards their political views than factual accuracy.”

The researcher relies mainly on a 2016 study7 that took place during the US presidential campaign, which shows that few people consume fake news out of a spirit of contradiction, in other words to try to sort out what is true from what is false, but rather to reinforce their worldview.

Recognising the more subtle forms

Lê Nguyên Hoang also argues that we should stop focusing on disinformation but suggests that the argument of inconsistent links between beliefs, attitudes and behaviours is contextual. “If we consider the status quo – that most people’s behaviour is good – then this argument is relevant. But if you look at an issue like climate change, inaction is dangerous. The fact that the subject is not sufficiently covered in the media can, in my opinion, be considered a form of disinformation.”

What the researcher describes here is the problem of mute news. This is a pernicious form of disinformation that consists of obscuring a key issue from media attention that often underlies the concerns of the public and political bodies.

Sacha Atlay qualifies the point, “on the subject of climate, it seems that it is the social media agenda of political parties that has become a predictor of the presence of this subject in the news.” Echoing mute news, the researcher mentions another technique often used: flooding. “This consists of flooding the information space with unreliable information in order to increase uncertainty and reduce confidence in reliable information”, explains Sacha Altay.

Indeed, climate issues seem to be increasingly covered by the media, as recent studies show8, although this depends on the country. For example, in Russia, the country’s climate policy is never questioned by the official newspapers9. In Western countries, the climate problem is often discussed at the level of communication; some groups doing so are specialised in flooding and are among the main producers of often misleading information10 on climate, ahead of scientific institutions or reliable media.

In conclusion, despite the initial opposition, both researchers seem to agree on the importance of increasing people’s interest in reliable information, which generally involves trust in the media. And even if, in the current context, our information ecosystems are colossal, highlighting the issues around disinformation is necessary for the well-being of society as a whole.