“Our desire for truthfulness makes us suspicious of institutions”

You have previously spoken a lot about the importance of good science communication during the pandemic. Was it a missed opportunity?

Etienne Klein. In a way, yes. During the pandemic, we heard many scientists talk, but we heard very little from “science”. We missed a historic opportunity to educate the public about science. On a daily basis, we could have shown how researchers work, the biases they fight against, their protocols, their mistakes, their successes. We could also have taken the time to explain certain important concepts like what a “double-blind trial” is, statistical analysis, exponential functions or how to distinguish between correlation and causality? Unfortunately, instead of doing this, we preferred to stage controversial debate between public figures.

For many months, the distinction between science and research were confused; they are two different things, even if they are not mutually exclusive. A scientist is someone who can say: “we know that” and “we wonder if”. The first half of this sentence refers to science, the second to research. Science represents a body of knowledge that has been duly tested and that there is no reason – until further notice! – to question: the Earth is round not flat, the atom exists, the observable universe is expanding, etc. But this knowledge, by its very incompleteness, raises questions about things that are not yet known to scientists (or to anyone else).

Answering such questions is the goal of research. By its very nature, therefore, research involves doubt, whereas science is made up of a set of givens that are difficult to question without extremely solid arguments. But when this distinction is not made, the image of the sciences, mistakenly confused with research, becomes blurred and degraded: they give the impression of a permanent battle between experts who can never agree, which just isn’t the case. From the outside, it is obviously a bit difficult to follow…

Is there currently much mistrust in science by the public?

The pandemic revealed something that already existed: the systematic suspicion of institutional discourse. The philosopher Bernard Williams observed two currents of thought in postmodern societies such as ours that are both contradictory and associated. On the one hand, there is an intense attachment to truthfulness: we have a desire to avoid being deceived giving us the determination to break through appearances in the search of possible ulterior motives hidden behind institutional messaging. And, alongside this perfectly legitimate refusal to be fooled, there is an equally great distrust of truth itself: does it really exist? If so, how could it be other than relative, subjective, temporary, local, instrumentalised, cultural, corporatist, contextual, fake?

Curiously, these two opposite attitudes, which should in all logic be mutually exclusive, turn out in practice to be quite compatible. They are even mechanically linked: the desire for truthfulness sets off a generalised critical process within society, which makes people doubt that there can be, if not accessible truths, at least proven untruths. All this weakens the credit given to the word of scientists and to any form of institutional expression.

Allow me a personal anecdote. When I explain fundamental physics phenomena such as the Higgs boson, no one suspects that my belonging to the CEA (French Centre for Atomic Energy) could influence my communication. But if I talk about radioactivity, then people often think that I am much more influenced by an institutional bias to CEA…

But how do you mark the difference between what you know and what you don’t know?

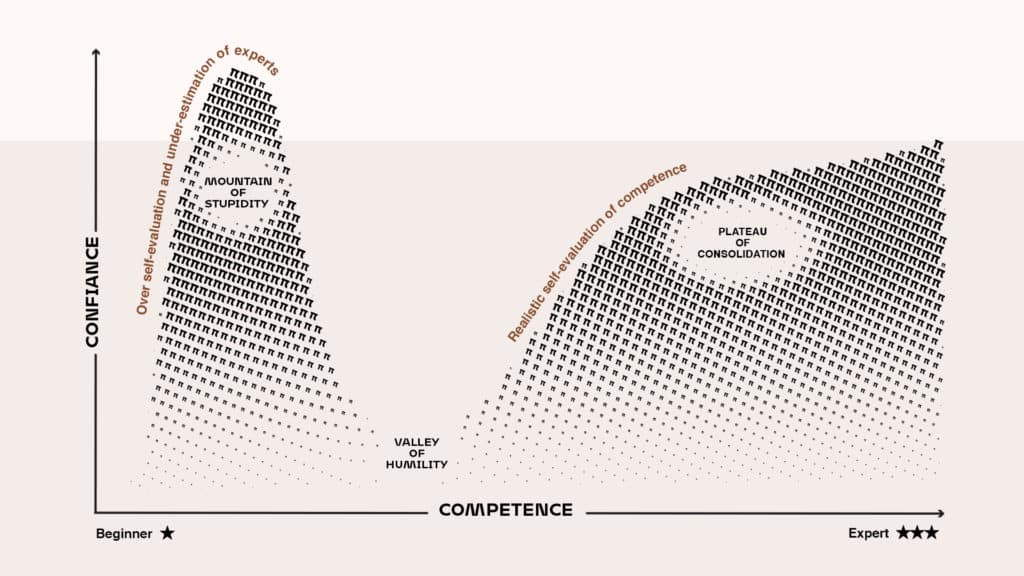

The boundary between the two evolves over time. We have also seen the typical dynamics of the so-called “Dunning-Kruger” effect unfold. This is a cognitive bias that has been identified for a long time and was studied empirically in 1999 by two American psychologists, David Dunning and Justin Kruger. The effect is based on a double paradox: on the one hand, to measure one’s incompetence, one must be… competent. On the other hand, ignorance makes people more confident about their knowledge. Indeed, it is only by digging into a question, by informing oneself, by investigating it, that we discover it to be more complex than we suspected.

At that point, a person then loses his/her self-confidence, only to regain it little by little as they become genuinely competent in that thing – but now treading with caution about what they know. During the pandemic, we saw the different phases of this effect unfold in real time: as we became more informed, as we investigated, we came to understand that the matter was more complex than we had suspected. Today, (almost) everyone, it seems to me, has understood that this pandemic is a devilishly complicated affair. As a result, arrogance is a little less widespread than it was a few months ago.

Is social media the culprit?

In part, because social media offers a way for each of us to choose our information and, with it, ultimately our “truths”. Digital technology even allows the advent of a new condition of the contemporary individual: as soon as we are connected, we can shape our own access to the world via our smartphone and, in return, be shaped by the content we receive persistently from social networks.

Thus, each of us builds a kind of customised world, an “ideological home”, by choosing the digital communities that best suit us. This creates what Tocqueville would have called “small societies”, with very homogeneous convictions and thoughts, each defending its own cause. In this world, we can go about life almost never being confronted with contradiction, since we only ever encounter confirmation biases… Thus, we become quick to declare the ideas we like as true to be the truth!

Do you think then that media should stop putting out “scientific debates”, to avoid wrong interpretation of the facts?

I have always defended the idea that scientists should express themselves publicly because I have always thought that there is a link between republic and knowledge: in a republic worthy of its name, knowledge, especially scientific knowledge, must be able to circulate without hindrance. The question that I would ask is rather this: “Is the way that the media, as is currently structured, adapted to the diffusion of scientific knowledge?” So-called ‘debates’ about scientific topics do not seem to be good tools to share scientific ideas. Perhaps we need to invent new forms of conferences, which give the time required to argue a point, to explain how we have come to know what we know. But this requires an amount of time that the media won’t or can’t allocate…

When I was younger, I thought that as soon as we had explained something clearly, the job was done. But no! Because there are so many cognitive biases at play, which modulate and distort the messages that are being sent out. So, it’s very complicated. I started communicating science almost thirty years ago, and at the time I had no idea how vast the task would be!

We must find a way to give credit back to the scientific content (you will notice that I prefer to speak of credit rather than trust). This will undoubtedly require a return to the use of the we rather than I: when it comes to transmitting knowledge, I prefer that a researcher speaks in the name of the community to which he belongs rather than in a personal capacity. Because science is indeed a collective endeavour. And the scientific community will then have to work to invent new ways of transmitting knowledge.