Carbon footprint and space activities: an ambiguous common ground

- There is a lack of knowledge concerning the impact of rockets on the upper atmosphere, particularly in relation to particle emissions.

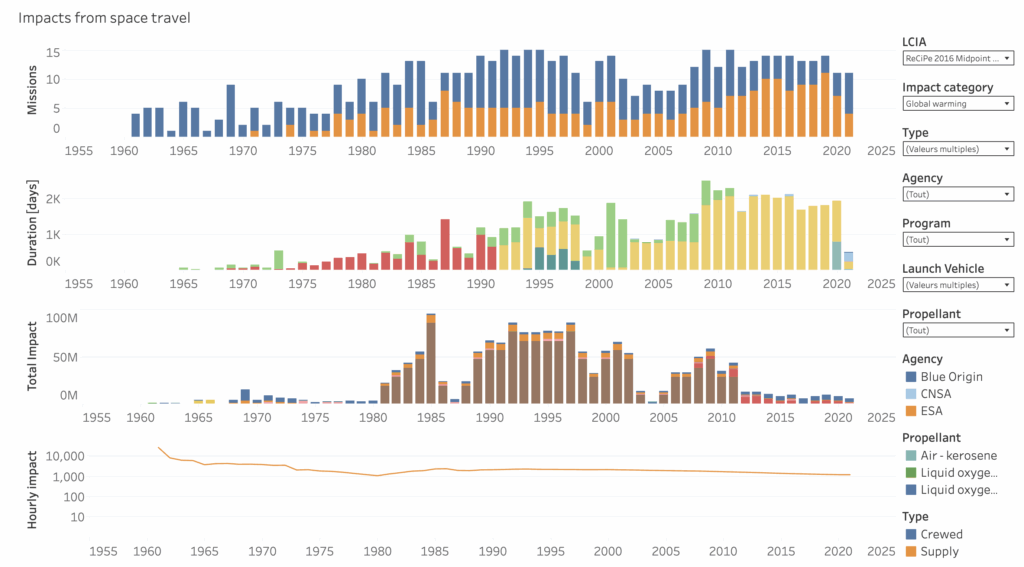

- Between 2019 and 2024, the amount of fuel used by rockets more than tripled, and at this rate, the climate impact of space activities could reach that of aviation.

- However, the cost-benefit analysis of Earth observation missions is difficult and requires debate and political arbitration.

- According to the CNES, the space industry’s carbon footprint at the national level amounts to 1.8 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent, or 0.3% of France’s national emissions.

- One of the current problems is linked to the increasing number of launches, which, through the use of reusable launchers, is creating a rebound effect.

Despite their significant carbon footprint, the space industry remains important for science and society. However, it is still necessary to prioritise its uses, because while space tourism has no societal value, observation missions are crucial to our understanding of the Earth. Loïs Miraux, an independent researcher and specialist in the environmental impacts associated with the space industry, and Jürgen Knödlseder, CNRS research director at the Institute for Research in Astrophysics and Planetology, share their expertise.

#1 Space tourism is an environmental disaster

TRUE

Jürgen Knödlseder. In light of the development of commercial space flights, Carbajales-Dale and Murphy calculated the carbon footprint of manned space flights1. Over the entire life cycle, they estimate that the climate cost amounts to 1,500 kg of CO₂ equivalent per hour. This is the hourly equivalent of 60 to 100 diesel buses running at the same time. For me, space tourism is not a priority.

Loïs Miraux. Space tourism damages public perception. It suggests that this is a model to follow and may discourage people from taking action to reduce carbon emissions in their daily lives.

#2 Space travel contributes to global warming

TRUE

LM. Space travel is the only human activity that impacts the upper atmosphere, particularly the stratosphere [Editor’s note: located between 12 and 50 km above sea level]. Some life cycle assessments (or LCAs) have been carried out, but very few have been made public.

Last June, as part of its roadmap for decarbonising the industry, the CNES revealed the very first global study on the carbon footprint of the space sector at national level. The industry’s annual emissions amount to 1.8 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (Figure 1), or 0.3% of France’s national emissions. These figures are higher than previous estimates made by scientists. Only one study from 2018 assesses the sector’s footprint on a global scale: emissions over one year are estimated at 6 million tonnes, or 0.01% of global anthropogenic emissions2.

Responsibility for the different phases – rocket construction, launch, fuel production, etc. – varies depending on the type of vehicle. The CNES estimates that the manufacture and transport of rockets and satellites account for the largest share of emissions. Other authors3 estimate the radiative forcing [Editor’s note: corresponding to the warming effect on the atmosphere] of rocket launches at 16 mW/m2. By way of comparison, the radiative forcing of aviation currently stands at 100 mW/m2.

#3 Earth observation data is necessary for monitoring climate change

TRUE

LM. Some applications of the space sector are essential, particularly scientific missions to study the Earth system and natural disaster management. The question of priority uses must be addressed.

JK. Many applications of the space sector are vital to modern society. I am convinced that Earth observation missions bring greater benefits to the planet than they cause harm. But this cost-benefit calculation is difficult and requires debate and political arbitration. Significant effort is also needed with regard to the data produced, as much of it is not used and, by pooling it, space missions could be optimised.

#4 The sector’s carbon footprint is quantifiable, and technological developments can mitigate it

UNCERTAIN

LM. When it comes to technological developments, reusable launchers naturally spring to mind. I conducted a life cycle analysis for CNES, which revealed that the climate impact was zero, but positive (20 to 30% savings) in terms of resources. Reusable launchers are heavier due to the additional components and fuel required for landing, which reduces their climate benefits.

We lack comprehensive knowledge regarding the effects of rockets on the upper atmosphere. Rockets release large quantities of particles (soot and alumina) into the upper atmosphere. These particles remain there much longer than when emitted into the lower atmosphere: the warming effect of soot is 500 times greater in the upper atmosphere than in the lower atmosphere. Almost all of the climate impact associated with rocket launches is linked to the emission of these particles. Reusable launchers will not help in this regard.

JK. One of the little-known effects that concerns us relates to the ozone layer. The impact of space activities could become comparable to that of human activities before the Montreal Protocol was implemented, which enabled its recovery.

#5 The space industry will always be a source of pollution

TRUE

LM. Technology will not be able to completely circumvent this. Even with the best fuels, rockets will always emit water vapour and nitrogen oxides, as well as metal particles when leaving or re-entering the atmosphere4, affecting the climate and ozone layer.

Added to this is the evolution of the sector. Historically, satellite missions covered scientific, military and telecommunications needs in a more balanced way. But the number of satellites in orbit has soared, particularly with Starlink: it has risen from around 2,000 in the 2010s to just under 13,000 today. Between 2019 and 2024, the amount of fuel consumed by rockets has more than tripled. If the current pace continues, the climate impact of space travel could reach that of aviation today.

UNCERTAIN

JK. The problem with space is mainly linked to the exponential growth in the number of launches. Technological developments such as reusable launchers are driving down costs and producing a rebound effect: the number of launches is increasing. I think international regulation is necessary; it is not reasonable to allow private actors to congest space.

Scientists, even though they account for only a small part of the sector’s carbon footprint, must also ask themselves questions. We have assessed the carbon footprint of astrophysics: it amounts to around one million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent per year, or 36 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent per year per astronomer. It is a very high-impact field of research. Space missions dominate the footprint, particularly the sending of probes to explore our planetary system. I question the value of this type of research; society should be able to decide how much of the remaining carbon budget should be allocated to it.

In the end, we have a huge amount of data that has never been exploited. For the past few years, I have been working exclusively on the archives. We have made some exciting discoveries, particularly regarding the hypothesis of the origin of positrons at the centre of the Milky Way.