Wormholes make for good science-fiction as ways for faster-than-light-speed travel between two extremely distant points in the universe. In reality, however, Einstein’s theory of general relativity shows that it would not be possible for matter to actually cross these “tunnels through space”. But physicists are still considering whether that hypothesis is false : quantum effects could play a role in refuting this hypothesis. Nevertheless, recent research is helping scientists better understand how wormholes could exist in a quantum theory of gravitation. And, in doing so, it may help solve Hawking’s famous “information paradox”1.

Are black holes “space portals”?

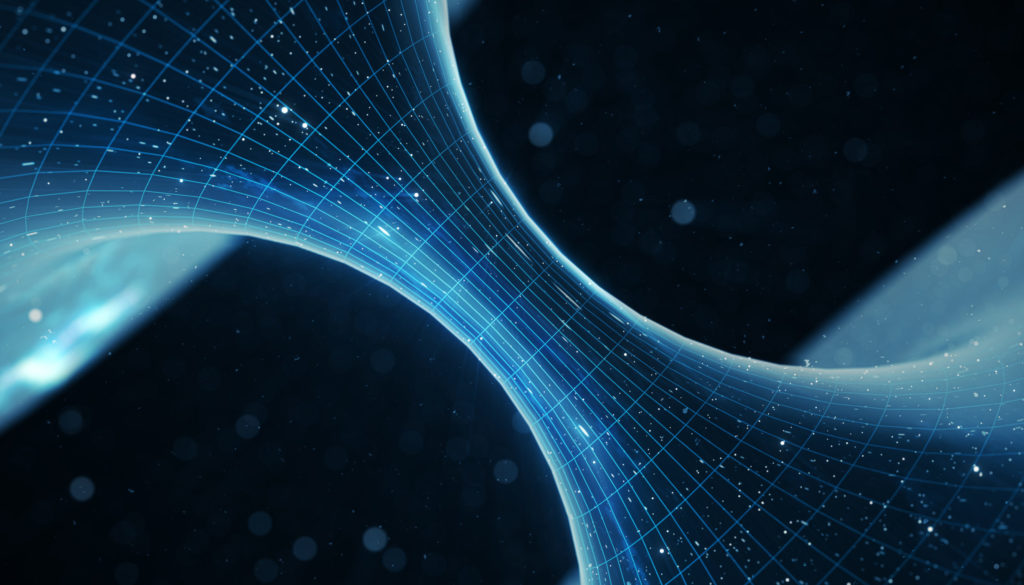

Wormholes are usually represented as a cylindroid connecting two sheets (or planes) of the universe – i.e., a tunnel between two black holes. In the classical description of general relativity (which neglects quantum effects), it is impossible to cross a wormhole without invoking exotic effects such as time travel. Furthermore, if a wormhole connects two black holes and those black holes pull everything near them into them (even light!), then surely it would be impossible to pass through a wormhole while escaping the force of gravity on the other side ?

To explain this, physicists theorised that “strong” quantum effects are at play. Indeed, recent work by Juan Maldacena (Institute of Advanced Study, Princeton) and Xiao-Liang Qi (Stanford University)2, goes some way in confirming this hypothesis. The duo used a very simplified model to show that it is possible to construct “negative energy” quantum states that produce a wormhole that can be travelled through. Negative energy (which, incidentally is thought to be responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe) is the energy that opposes the force of gravity and, as such, would keep the “mouth” of a wormhole open.

Quantum effects

What is most physically interesting in Maldacena and Qi’s hypothesis is not so much the possibility of wormholes we could cross, but rather its relationship to the “information paradox” put forward by Stephen Hawking – a very active area of research34 !

A black hole is formed when a very massive star dies and its residual core has a mass three times that of our Sun. Black holes of this size are so dense that they curve the structure of space-time around them to such an extent that nothing can escape, not even light. But Hawking predicted in 1974 that, even though black holes absorb everything, they could somehow themselves emit particles in the form of radiation (this is known as the “Hawking radiation”)5. These particles are created by so-called “quantum events” at the edge of the black hole (its “event horizon” or “point of no return”).

According to quantum theory, the vacuum of empty space is not a true vacuum, but contains “virtual particles”: pairs made up of a subatomic particle and its antiparticle (an electron and a positron, for example). These particles may briefly come into existence in a random quantum fluctuation, before annihilating one other.

The situation is quite different at the event horizon, however. Here, one of the pair might fall into the black hole while the other escapes and becomes a real particle. This process draws (gravitational) energy from the black hole, which reduces its effective mass. The black hole then slowly evaporates, while Hawking radiation streams from its surface. This radiation is extremely weak, and in theory, a black hole of one solar mass would take 1058 billion years to evaporate completely – and the universe is not even 14 billion years old.

Inextricable links

This evaporation also poses another difficult theoretical problem, related to “quantum entanglement” (a process by which particles become inextricably linked). The particles emitted by the Hawking radiation are entangled with the quantum state describing the black hole. But if the black hole ends up evaporating completely – and thus disappears – there would be no black hole quantum state with which Hawking radiation particles can entangle. So, according to quantum theory, it should be possible to have a situation in which a particle would be absorbed by the black hole while its antiparticle would “evaporate”.

To overcome this apparent paradox, most theorists believe that Hawking radiation is maximally entangled with the black hole only during the first part of its evaporation (roughly its “half-life”). In the second part, the black hole would emit radiation entangled with the radiation emitted in the first moments of its life. Once it has evaporated, the quantum entanglement would therefore only occur between particles radiated at distinct moments in time.

Semi-classical states

The challenge for physicists is to provide a quantitative explanation for these ideas using a quantum theory of gravitation. The so-called semi-classical approach (so called because it describes the matter in and around black holes using quantum theory, but describes gravity using Einstein’s classical theory), considers quantum effects as being weak.

No one has been able to provide a satisfactory description of this phenomenon. According to Maldacena and Qi, the explanation lies in the idea that when a black hole is young, the classical description of Hawking radiation holds. With time, however, new semi-classical states, involving a wormhole that links the black hole to the radiation it emitted in its early days, become more important. As the black hole evaporates, these new states eventually end up including wormholes outside the black hole. These new wormholes describe the quantum entanglement between the early and late-stage radiation.

Finally, these wormholes are virtual and there is no question of traversing them, but they play an important role in describing the phenomenon of black hole evaporation. Even if their models are very simplified, researchers can now accurately describe that the entanglement entropy – which measures the rate of entanglement between the radiation and the black hole – follows the so-called Page curve6, in a way that resolves Hawking’s information paradox.