Photonic propulsion: visit the Solar System by sail

- In the search for a new method of space propulsion, a sail pushed by light has been theorised.

- Unlike other space propulsion methods, which always require a fuel tank to be heated and ejected backwards to push the spacecraft forward, it would be pulled using a sail.

- This idea of small but continuous thrust that has led several research groups to test increasingly sophisticated prototypes in recent years.

- The sails themselves are the subject of intense research to optimise the way they interact with light. NASA, for example, is developing a so-called ‘diffractive’ solar sail.

- There are plans to build a 100GW laser beam array on Earth, gradually accelerating small sails to 20% of the speed of light, which would enable them to leave the Solar System by 2030 and fly past Proxima Centauri around 2060.

Despite the extraordinary technological advances in the field of space, it is clear that the principle of spacecraft propulsion has not changed much. This principle is called action-reaction: the faster we throw a large amount of matter in one direction, the more force we create in return to move forward in the other direction.

This is how a small steam engine was powered back in the 1st Century AD, and it is the same principle that governs the lift-off of the Ariane 5 launcher or the movement of the Japanese Hayabusa 2 probe around its asteroid Ruygu. So, as long as we are taking inspiration from ancestral techniques to move around in space, why not use the same means that has long allowed mankind to pilot and propel its boats to discover new continents: the sail?

In space, no one can hear you scream…

This, now famous, pop-culture phrase was the tagline for the “Alien” series of science-fiction films and reveals a fundamental aspect of space: there is no air. For sound to propagate, a material medium (gas, liquid or solid) is needed, so it is impossible to call for help in the vacuum of space. And therefore, if there is no air, there is no wind either. As such, even our finest sailing ships would be ill-advised to try to move outside the Earth’s atmosphere. Fortunately, however, this does not spell the end of our plans for space sailing ships. Indeed, what is improperly called the “vacuum of space” is not entirely empty.

While the volume of matter is reduced to a few atoms per cubic centimetre, space is filled with photons: in other words, particles of light. At the level of the Earth’s orbit, each square metre of surface receives about 121 (1,000 billion billion) photons from the Sun every second. When a photon bounces off a surface, it transfers a tiny amount of energy to the surface in the form of recoil. This effect of the pressure of light on matter has been observed for centuries.

In 1619, the great astronomer Johannes Kepler suggested that the orientation of a comet’s tail was due to the ‘blowing’ effect of the Sun’s light. The first mathematical explanations came later, from the famous physicist James Maxwell in 1873, and the first measurements of this tiny effect of light receding from a wall were made a few years later, at the very beginning of the 20th century.

So, in theory, it is possible to build a sail pushed by light. But is this thrust sufficient? How big would a space sail have to be to capture enough photons to move under the sole effect of sunlight?

Possible, promising, but complicated

Calculations show that in order to accelerate 1kg of matter and increase its speed by 1 m/s every second, a sail of about 100,000 m² is needed at the level of the Earth’s orbit, i.e. a square sail of about 330 metres on each side. Hence, you need a very large surface area for still a very small acceleration. At this stage, it would be tempting to declare this method ineffective, throw the paper on which these calculations were made in the bin and move on to another research topic. But this would be to miss a crucial piece of information that has not been considered so far. This energy source is free and never-ending!

Indeed, the Sun has been burning for almost 5 billion years and will continue to do so for just as long. Unlike other space propulsion methods, which always require a fuel tank to be heated and ejected backwards to push the spacecraft forward, no tank is needed here. There is no need to worry about breaking down!

And if the start of our solar sail’s journey was quite modest, let’s not forget that the acceleration would be constant, and could be maintained for years, even decades!

Continuing with the calculations started above, it is shown that after 100 days of operation, under realistic conditions, a solar sail could reach 14,000 km/h. Three years later, its speed would reach 240,000 km/h. This would be enough to reach Pluto, one of the most distant bodies in the Solar System, in just five years. (By way of comparison, it took the New Horizons probe almost 10 years to make the same journey)

From theory to practice

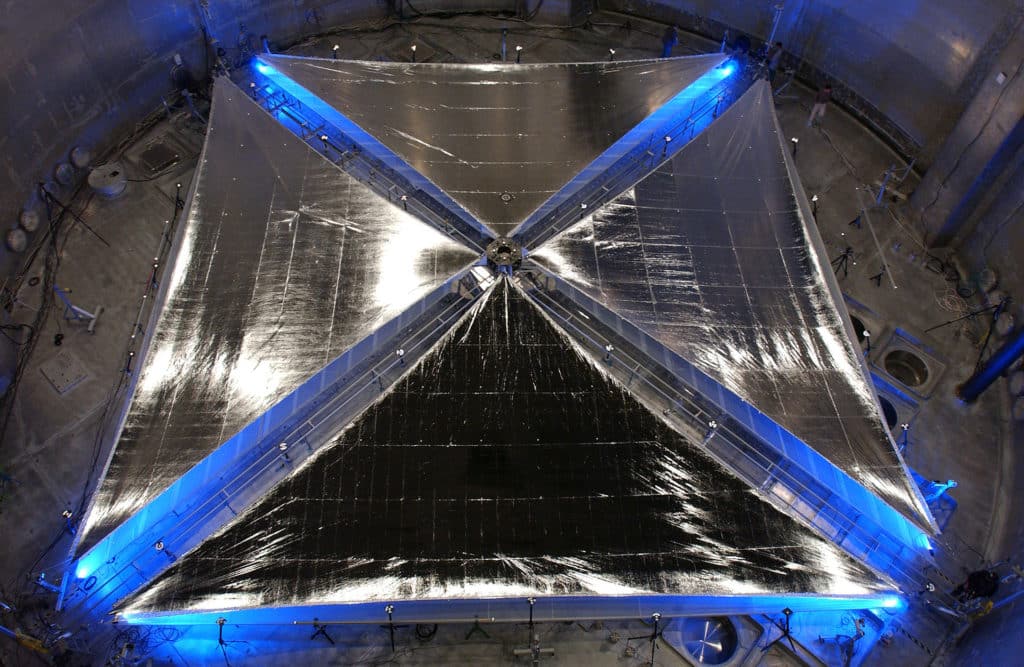

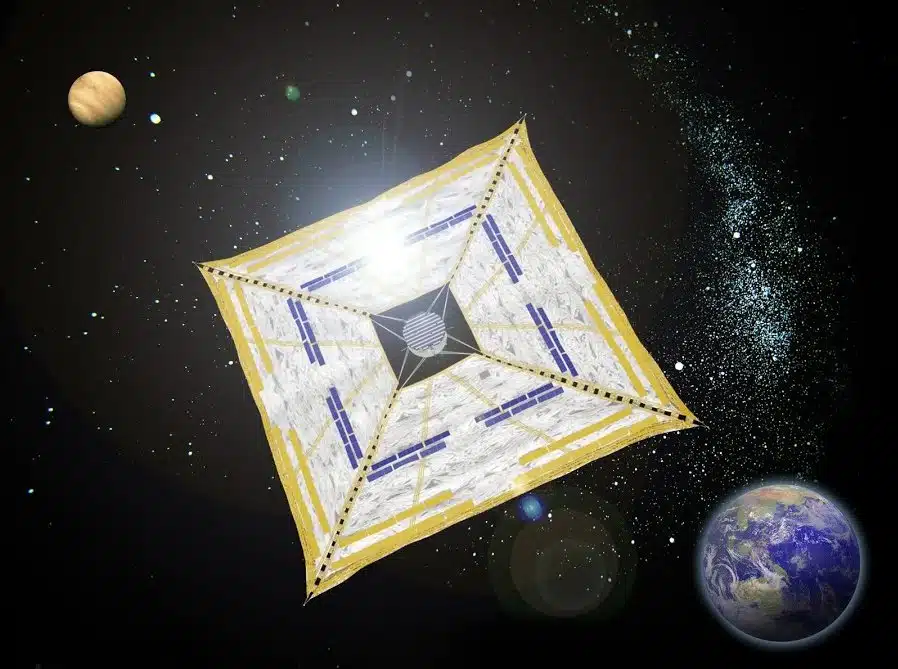

It is this idea of a small but continuous thrust that has led several research groups to test increasingly sophisticated prototypes in recent years. The first solar sail was developed by the non-profit organisation The Planetary Society. The payload consisted of a central body weighing 100 kg surrounded by eight small solar sails of 30 metres each. In 2001, a first launch of the prototype ended in failure. The prototype was rebuilt and launched in 2005 by an old intercontinental ballistic missile from a Russian submarine. Once again, communication was quickly cut off and no one heard anything more about the device. These difficult beginnings do not discourage researchers and physicists. In 2010, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) sent the 14-metre IKAROS solar sail into orbit.

LightSail 1 and LightSail 2, built by The Planetary Society and sent into space in 2015 and 2019 respectively, will follow, confirming the possibility of attaching a solar sail to a satellite to modify its orbit. This time it was successful. After one month, the speed of the 315 kg craft (including 15 kg of sail) has increased by about 10 m/s. The Japanese agency has thus validated the principle of the solar sail and confirmed that it is possible to deploy and steer such a craft in space.

Prospects and the future

One of the shortcomings of early solar sails was that they could only set small payloads in motion at the centre of the sail. The first prototypes were too heavy to be accelerated significantly. Today, the development of new technologies, the use of new materials and miniaturised electronics have made it possible to build nanosatellites weighing just a few kilograms, with performances that promise to be as good as today’s huge satellites weighing several hundred kilograms, thanks, among other things, to the use of on-board artificial intelligence algorithms.

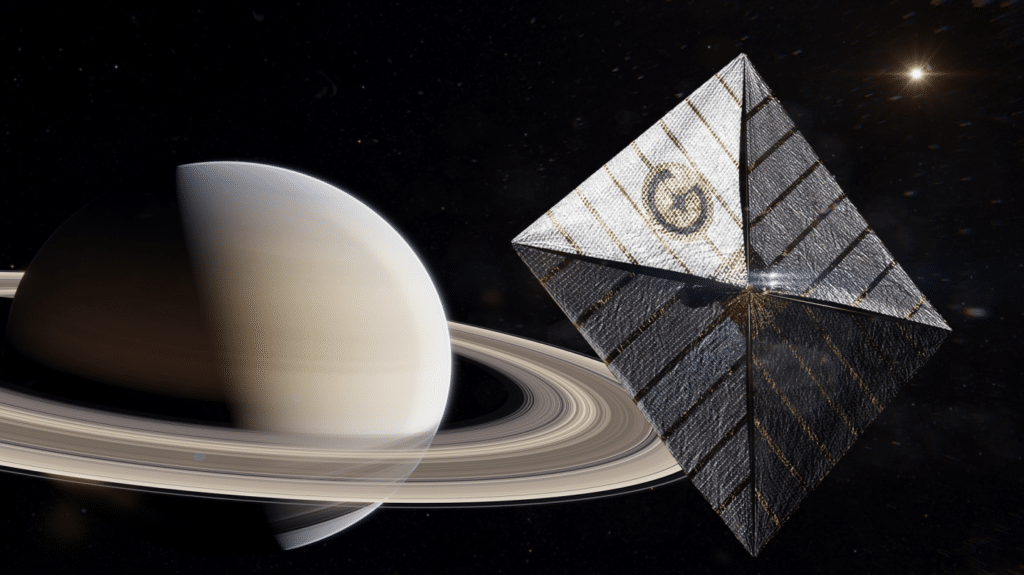

The sails themselves are the subject of intense research to optimise the way they interact with light. NASA, for example, is developing a so-called ‘diffractive’ solar sail. This project, Diffractive Solar Sailing, uses small optical gratings embedded in the sail’s thin films to make more efficient use of sunlight, without sacrificing the craft’s manoeuvrability.

Finally, it should be remembered that the space landscape has undergone intense and profound changes in recent years. The evolution of techniques and the drop in the cost of access to space now allow new start-ups to test and commercialise innovative space-related processes and services. This new dynamic is known as “New Space”.

One of these French startups, Gama Space, recently raised $2 million from the CNES (Centre National d’Études Spatiales) to develop a small 72 m² solar sail, 50 times thinner than a human hair, which should initially serve as a propellant for a small 11 kg satellite launched in October 2022. Of course, the aim is not to limit itself to Earth orbit, and Thibaud Elzière, its founder, is already thinking of a means of directing future exploratory probes throughout the Solar System…

To infinity and beyond!

The final limitation inherent in the solar sail technique is, of course, the number of photons that ‘push’ the craft. And the further away from the Sun the sail is, the faster this quantity decreases, until it has almost no effect on the craft.

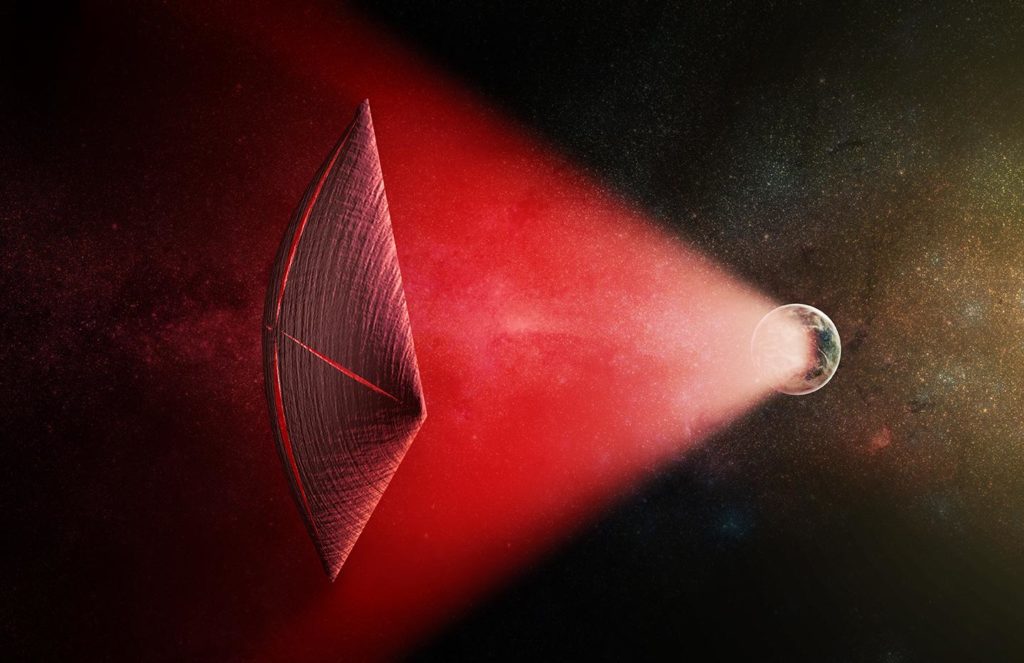

To solve this problem and envisage space exploration outside our Solar System, the StarShot project plans to build a thousand small solar sails, each weighing no more than one gram. In order to reach Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun, in a reasonable time, it is planned to build a 100-Gigawatt laser beam array on Earth, gradually accelerating these small sails to 20% of the speed of light, which would enable them to leave the Solar System by 2030 and fly past Proxima Centauri around 2060.

Will we have detailed images of another sun and the planets around it by the end of the century? All it takes is a few photons and a little human ingenuity…