What are the risks of space for humans?

- Humans are not naturally equipped to live in space so many precautions must be taken when leaving the surface of Earth.

- Technical and technological improvements have made it possible to avoid the inconveniences caused by old space equipment.

- However, the human body undergoes many changes: congestion, loss of taste, loss of muscle mass or even weakening of the bones.

- Exposure to cosmic rays can cause changes ranging from cataracts to increased risk of cancer to infertility.

- Much work remains to be done to create a viable space environment for humans in the long term.

It is no surprise that humans are not naturally equipped to live in space. Exploring it requires a great deal of technical adaptation, years of training, not to mention high morale and physical fitness. The first human spaceflight took place on 12 April 1961, when Yuri Gagarin made his only trip around the Earth in the Soviet Vostok capsule.

Although human presence in space was once rare, there have been people in space continuously for the past two decades mainly thanks to the famous International Space Station (ISS), where astronauts from different countries take turns working in and outside the station.

Space is often referred to as being very dangerous for humans, but what are the risks of venturing into this extreme environment? How can they be minimised? Is a space accident possible? And what influence does space travel have on a human being?

An eventful history

The main problem in space is that there is not just one hazard to watch out for, but a multitude of factors that if not properly considered can all lead to critical situations. And we learned this from the very beginning of the space age.

One of the first incidents occurred just four years after Gagarin’s first flight. He remained in the pressurised cabin of his spacecraft throughout his journey whilst his counterpart Alexei Leonov attempted the first spacewalk in a spacesuit. After ten minutes outside the spacecraft, he decided to return but realised that the air pressure inside his suit had inflated so much that he could no longer fit into the airlock. As a result, he had no choice but to risk letting the air escape from his suit, reducing the pressure to 1/3 of atmospheric pressure (at the risk of a gas embolism) to finally be able to return to the safety of his ship. Today, there is no longer any risk of such an event happening. Firstly, because spacesuits are much less flexible and elastic than Leonov’s and, secondly, because modern spacesuits operate under a pure oxygen atmosphere, which means that the interior can be subjected to much less pressure than Leonov experienced.

But a spacesuit (called the EMU or Extravehicular Mobility Unit for the American model and the Orlan for the Russian model) is not only used to maintain a breathable atmosphere and bearable atmospheric pressure for the astronaut. It also protects against another extreme environmental constraint in space: temperatures.

In fact, in a vacuum, with no warm air to “stir up” the temperature around the astronaut, the temperature differences between the lighted and dark sides are gigantic. The illuminated parts, which are directly exposed to the Sun’s rays, can rise to 120°C, while the temperature of the shaded parts can drop to ‑100°C. As such, water-cooling circuits are integrated into one of the layers of the suit to redistribute the heat from the hot parts to the cold parts and maintain a bearable interior temperature for the astronaut. And everything is fine… so long as this cooling system does not leak!

On 16th July 2011, while outside the Space Station, Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano of the European Space Agency felt water on the back of his neck. In weightlessness, water behaves in a peculiar way: it curls up and floats in front of the amused astronauts. But if it touches a human’s skin, it sticks to it, held in place by a force called “surface tension”… which is fine when you have a cloth to wipe it off, but can be much more serious when you are alone in your suit, unable to touch your own face, and the water builds up more and more, threatening to gradually cover your eyes, nostrils or suit visor.

Fortunately for Luca, the spacewalk is immediately aborted and, with the help of his partner, astronaut Christopher Cassidy, he manages to re-enter the Station with his eyes closed, the microphone and then the headphones gradually turned off by the advancing water. Once the pressure was restored in the airlock, the crew on board entered in a hurry, unscrewed the helmet, and finally sponged off the water which, after examination, was indeed coming from the cooling system.

Influence(s) on the human body

The simple fact of being safe in the ISS does not prevent the human body from undergoing a certain number of changes, at all levels (body, organs, cells, genetics). The discomfort usually starts when the astronaut arrives on board. Used to pumping blood upwards to counteract gravity, the heart continues to work even when the human in question is weightless and no longer feels its own weight. The result is a red, swollen head, characteristic of these microgravity states.

This congestion of the head and, among other things, of the nasal mucous membranes, which are also swollen with blood, has a direct impact on the taste of the food eaten there. In such a situation, the air does not circulate well in the nose. As the sense of smell is a significant part of the taste sensation of food, it loses much of its flavour (this loss will be compensated for in part by sending spicier-than-average dishes).

The loss of muscle mass, if not compensated for by two hours of sport a day, can have serious consequences.

But the impact on the human body can be more problematic. In weightlessness, a simple push against a wall is enough to propel you to the other side of the Space Station. In fact, you use your muscle structure much less than on Earth. This results in a loss of mass which, if not compensated for (or at least slowed down) by two hours of sports sessions per day, can have serious consequences upon return to Earth.

In parallel with this loss of muscle, the bones also become more fragile and brittle. This pathology, generally reserved for elderly people on Earth, is called osteoporosis. Even if this bone decalcification is reversible once back on the ground, a study1 conducted on 14 men and 3 women – before and after their stay in space – showed that even after one year of rehabilitation, the resorption of the astronauts’ tibia structure was still incomplete. And of course, the longer the stay in space, the longer the return to normal.

What are the effects of space radiation?

There are many medical effects on the human body during a prolonged stay in weightlessness: dizziness due to imbalances in the inner ear, changes in eye pressure that can lead to retinal detachment, urinary retention, kidney stones, etc. However, there is one final danger that should not be underestimated: the effect of radiation.

In space, cosmic rays form a shower of so-called “ionising” particles. Prolonged exposure to these rays can cause macroscopic changes (burns, cataracts) and microscopic changes (genetic alterations, sterility or increased risk of developing cancer). These cosmic rays are essentially composed of protons, electrons, and atomic nuclei, propelled into space by the Sun (for low-energy cosmic rays) and other much more violent phenomena such as explosions of massive stars or black holes swallowing matter (causing high-energy cosmic rays).

Intensive research is being carried out to protect astronauts from space radiation.

On Earth, we are well protected from these cosmic rays thanks to the Earth’s magnetosphere which deflects a substantial part of this particle flux, and the atmosphere which physically stops the little that remains. In space, we can no longer rely on the protection of the atmosphere (which is at a lower altitude). And even though the magnetosphere still plays a role for the ISS, which orbits at an altitude of only 450 km, the same is not true for when humans venture further into the Universe: the Moon in the near future and to Mars in the longer term.

This is why intensive research is currently being carried out, both on ways to protect astronauts from this space radiation. But also on tools to measure the radiation dose received on a daily basis, and on the biological effects of this radiation.

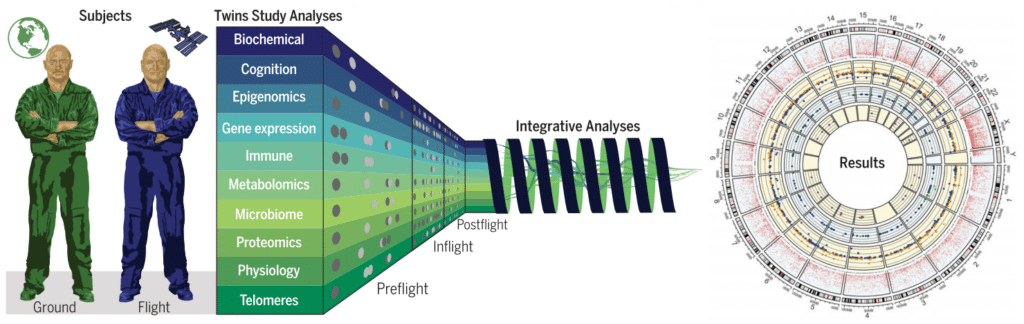

In this respect, one of the “most comprehensive assessments we have ever had of the human body’s response to spaceflight” comes from a remarkable study2 carried out in 2015 on two twin brothers (Mark and Scott Kelly), one of whom stayed in space for 340 days while the other remained on Earth. It was then possible to follow these two genetically identical men and to observe precisely the changes brought about by the space environment at different levels (biochemical, immune, genetic, physiological etc.).

The conclusion is that space travel significantly alters the functions of the human body, and while the vast majority of these are restored once back on the ground, much work remains to be done to create a viable space environment for humans in the long term.