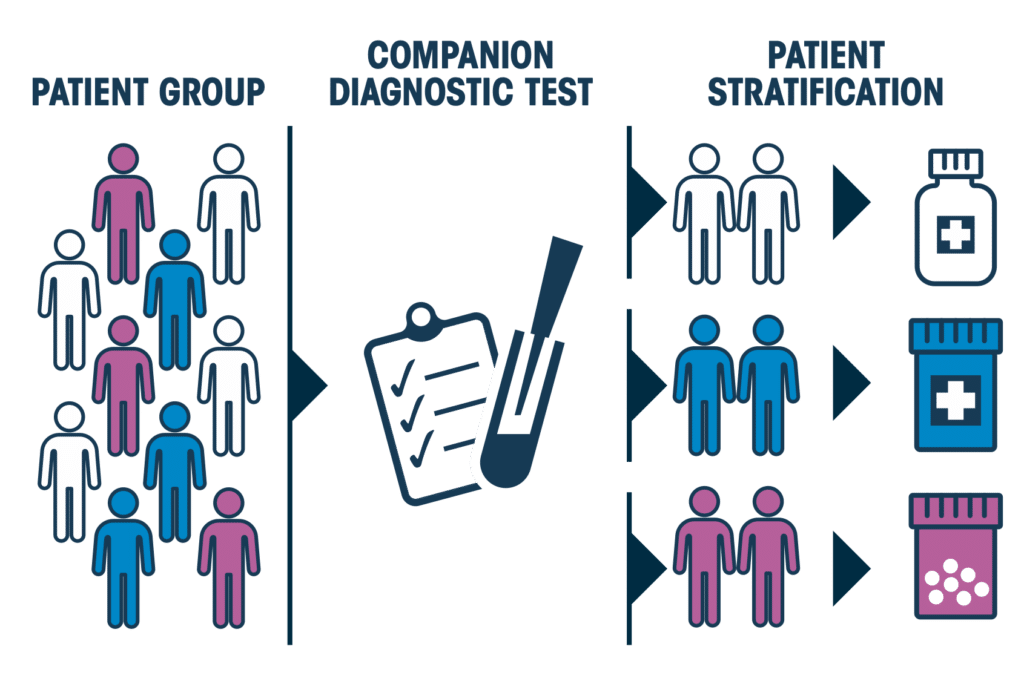

Personalised medicine, sometimes referred to as precision medicine, owes its origins to extensive developments in DNA sequencing techniques. It is an approach which aims to provide treatments tailored to patients that target the specific mechanisms causing their disease, particularly cancer. Molecular profiling of tumours, for example, has revealed their remarkable diversity. Their characteristics have been used to identify distinct patient subgroups from those which previously seemed similar in terms of other clinical criteria. As such, treatment quality can be vastly improved by treating patients in each subgroup with an optimal medication plan.

“In a perfect world, we would be able to design a different treatment for each patient based on the molecular characteristics of their tumour,” notes Alexis Gautreau, biology professor at Ecole polytechnique. “But personalised medicine is not only about treatment. Rather, it is the combination of molecular diagnostics and medication,” with diagnosis providing the basis for the choice of medication.

Spectacular results

Results have been impressive, as shown by trastuzumab used in the treatment of breast cancer; one of the first “personalised” medical treatments. It precisely targets some of the most aggressive cancer cells, while leaving healthy cells intact. As a result, trastuzumab is now a crucial part of treatment for breast cancer patients with a particular genetic variant. Compared to “standard” treatment with emtansine, it has increased progression-free survival by at least three months and overall survival by over ten percent. It is now administered in combination with conventional chemotherapy and increases patient survival rate by 10%.

Other approaches directly target genetic mutations. This is how treatments for cutaneous melanoma (skin cancer) with the BRAF-V600 mutation work. They specifically inhibit the mutated form of an enzyme within the tumour, without affecting the normal protein in the rest of the organism. In other words, by correcting the misfunction caused by the mutation it treats the cancer at its root.

Many of the breakthroughs in personalised medicine are the result of collaboration between academic researchers, start-ups and industry. Companies realised that treatments that were unsuccessful on a large group of patients could still work on a smaller, specific subgroup. Hence, taking another look at molecules, which had previously been discarded due to unconclusive results. This “drug repositioning” approach saves time and money as it bypasses some of the pre-clinical and early clinical development phases.

What’s more, using targeted treatments, the location of cancer in a patient is not necessarily the determining factor in treatment success. For instance, the same medication can often be used to treat patients with pancreatic and lung cancer, alike.

“Targeted therapy works very well and produces fewer side effects than conventional treatments,” Gautreau says. “After receiving these treatments, people start believing in miracles. However, relapses are still commonplace.”

Not the end of the story

Indeed, after months of tumour decline, doctors often observe relapses as the cancer evades targeted therapy. One of the reasons for this is that all tumours are different. Not only do doctors observe genetic differences in tumours from different patients; they also find variations within one tumour, as one cancer cell differs from another.

Targeted therapy is effective against a tumour when it is effective against the majority of cells. Some cells die under the effect of the treatment, while others, with different mutations, resist. Out of the overall patchwork of cancerous cells, cells that don’t respond to treatment eventually form a new tumour, which replaces the original one.

For this reason, collaboration between doctors and biologists is crucial. “Biologists have lots of models, in the form of cell cultures or mice, for example. But these do not necessarily do a good job in showing how the disease progresses in humans. To represent human tumour that is 3 cm in diameter, we use a 1 mm tumour in a mouse, which has much fewer cells and therefore less diversity. We know how to cure mouse cancer! For humans, it’s more complicated,” Gautreau acknowledges.

Still in the dark

A combination of targeted therapies would seem to be a logical solution. But tumours still manage to escape. “We have observed escape phenomena that we do not understand,” Gautreau emphasizes. “It would seem that cancerous cells can change when attacked by medication. They mutate in order to survive.” In real-life, this phenomenon occurs even more frequently than mathematical modelling predicts.

As such, biomedical researchers are turning to AI in the hopes of solving the mystery. “If the question could be cracked using computers alone, that would be great,” he admits. “But I think that we have put enough effort in to realise that we need more experimental data to chew over, and a better understanding of the laws of biology at play.”