First predicted in 1964 by theoretical physicists, including Peter Higgs and François Englert (2013 Nobel laureate), to explain why some particles have mass, the Higgs boson was discovered in 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). This particle gas pedal located at CERN on the French-Swiss border produced the famous particle as a result of collisions between protons of very high energy.

During these collisions, the LHC reached a record energy of 7000 GeV, allowing particle physics researchers to reproduce the physical conditions of the first moments of our Universe – a fraction of a billionth of a second after the Big Bang – in laboratory conditions. They were thus able to glimpse at the first time the moment when the elementary particles that constitute ordinary matter appeared in the budding Universe.

The Higgs field

Physicists have known since the 1970s that two of the four fundamental forces of nature – weak force and electromagnetic force – are closely related. These two forces can be described within the framework of a single theory, which forms the basis of the Standard Model of particle physics. This ‘unification’ implies that electricity, magnetism, light and radioactivity are all manifestations of a single underlying force, known as the electroweak force.

If the basic equations of the unified theory correctly describe the electroweak force and the particles that carry it, namely the photon and‘vector bosons’, W and Z, there is a major hitch: all these particles appear to have no mass in calculations. If the photon is indeed massless, the W and Z have a mass almost 100 times that of a proton. To solve this problem, theoretical physicists Robert Brout, François Englert and Peter Higgs proposed a mechanism that gives mass to the W and Z particles when they interact with an invisible field, called the ‘Higgs field’, which permeates the entire universe.

Spontaneous breaking of the electroweak symmetry

Just after the Big Bang, the Higgs field was zero, but when the Universe cooled down and its temperature fell below a certain critical temperature, the Higgs field spontaneously increased so that any particle interacting with it acquired a mass. The more a particle interacts with this field, the heavier it becomes. Particles like the photon that do not interact with it remain massless while the W and the Z have mass.

This sudden increase of the Higgs field led to the spontaneous breaking of electroweak symmetry, with the striking consequence that the weak interaction was suddenly carried by the W and the Z. At the same time the photon of zero mass appeared, as a vehicle of the electromagnetic interaction. As a result, the weak interaction, responsible for radioactivity, acts only at very short distances, while the electromagnetic interaction has an infinite range. With the appearance of the mass of elementary particles, such as the electron or quarks, and that of the electromagnetic interaction, which makes it possible to define the electric charge as we know it, the ingredients necessary for the formation of the atoms of ordinary matter finally appear in the Universe.

The discovery of the century

Like all fundamental fields, the Higgs field is associated with a particle – in this case, the Higgs boson. The Higgs boson is the visible manifestation of the Higgs field, much like a wave on the surface of the sea. For many years, however, there was one major problem: no experiment had ever observed the Higgs boson to confirm this theory. On July 4, 2012, the large CMS and ATLAS experiments at CERN, both announced the discovery of a new particle in the mass region around 125 GeV.

The Laboratoire Leprince-Ringuet (LLR), with the support of CNRS and École Polytechnique, was among the main players of this “discovery of the century” – as part of the international collaboration, CMS. It has since contributed to the precise determination of the intrinsic properties of the Higgs boson and its couplings to other elementary particles. It has also been confirmed that it is a ‘scalar’ boson, in a kind of its own, because it has no “spin’”: it is neither a matter particle, such as the electron (spin = ½), nor the vehicle of an interaction such as the photon (spin = 1). LLR researchers have also demonstrated that the Higgs boson couples to other particles of matter with an intensity proportional to their mass.

An intense program of improvements

The current results of the ATLAS and CMS experiments indicate that the Higgs boson does indeed seem to have all the characteristics of the elementary particle predicted by the spontaneous symmetry breaking mechanism at the origin of the mass of particles in the Universe. To better understand these results, we need to measure how the Higgs boson couples with itself. In practice, this means being able to access the production of H‑boson pairs, which will only be possible by pushing the performance of the large proton-proton collider at CERN to the maximum. To achieve this, an intense program of improvements to the collider and the large particle detectors is underway in preparation for a new phase of operation of the LHC at very high luminosity, called HL-LHC, from 2027. The luminosity of a collider is a quantity proportional to the number of collisions occurring in a time interval. The integrated luminosity during the HL-LHC phase should allow the ATLAS and CMS experiments to increase the number of collisions recorded by a factor of at least 10. This increase in sensitivity should not only give access to the production of H‑boson pairs, but also allow to extend the search. We could thus observe, who knows, the direct production of dark matter (which would constitute 27% of the matter of the Universe and which remains an enigma for physicists), or the additional scalar bosons predicted by various theories going beyond the Standard Model.

An innovative calorimeter to push the limits

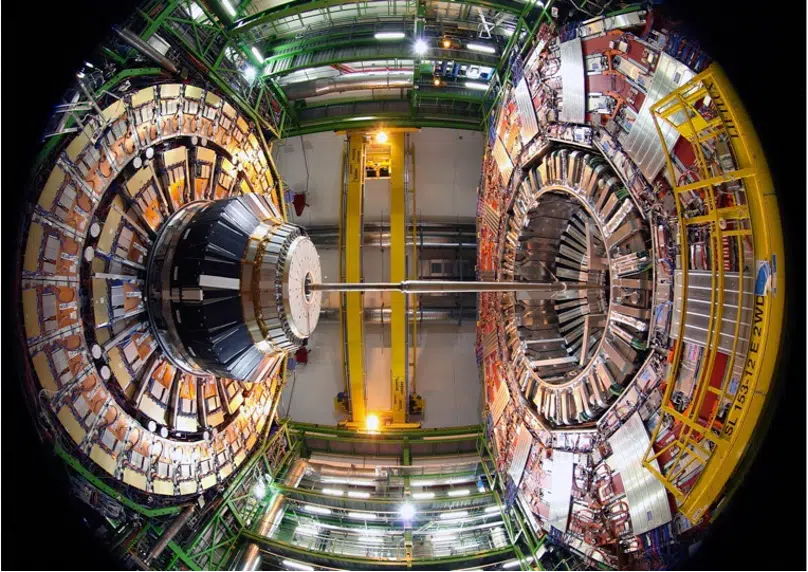

The Leprince-Ringuet laboratory is involved in the development of the mechanics and triggering electronics of a new type of calorimeter for the CMS experiment at HL-LHC. The aim is to build two identical detectors to replace the current end caps (see photo below) closing the front and rear ends of the cylinder formed by the experiment, and which will have to survive an extremely hostile environment, with integrated radiation doses of up to 2 mega Gy and a fluence of 1016 neutrons per cm2. The detectors must also be able to cope with a proton beam crossing frequency of 40 MHz, while sorting out the hundreds of collisions that will occur at each crossing.

The solution adopted is necessarily particularly complex. It is a high granularity calorimeter called HGCAL, with reading planes made of silicon tiles on tungsten bases and lead absorber planes. The granularity of this new calorimeter is unprecedented in high-energy physics, with more than 6 million readout channels per tip for 0.5 and 1.0 cm2 silicon cells, all feeding analog signals to state-of-the-art electronic chips developed onsite at IP Paris by the OMEGA laboratory. The HGCAL will provide a complete reconstruction of the energy, impulse, and time of flight of the different particles produced at the collision point. It will be a key element for the reconstruction of the particle flux created by each collision, with a major impact on all physics analyses at HL-LHC.