A new generation of space missions is under way. Their aim is to measure the electric and magnetic fields of space plasmas as well as particles (electrons, protons and heavy ions). A better understanding of these fields allows researchers to study phenomena like turbulence in the solar wind and how it interacts with planetary magnetospheres.

The effects of solar wind

The results of these missions are of great importance, not only for understanding these effects, but also for better characterising large-scale structures. For example, coronal mass ejections in the solar wind generate so-called ‘solar storms’ that impact the Earth’s magnetised environment1. These can damage electricity and communication networks and satellites if they are strong enough.

Solar wind is an ionised gas, known as a plasma, composed mostly of electrons and protons. It is continuously ejected from the Sun’s upper atmosphere in all directions into interplanetary space, along the magnetic field lines emanating from the Sun. It has two components: a ‘fast’ wind moving at about 500–800 km/s from coronal holes at the poles of our star and a ‘slow’ wind travelling at about 200–400 km/s emitted mainly at the equatorial plane of the Sun. When the solar wind collides with particles in the Earth’s atmosphere, many photons are emitted in the same amount of time, creating the beautiful polar auroras that can be seen at high latitudes in the northern and southern hemispheres. These auroras are known as aurora borealis and aurora australis, respectively.

Cluster et Cassini, Parker Solar Probe et Solar Orbiter

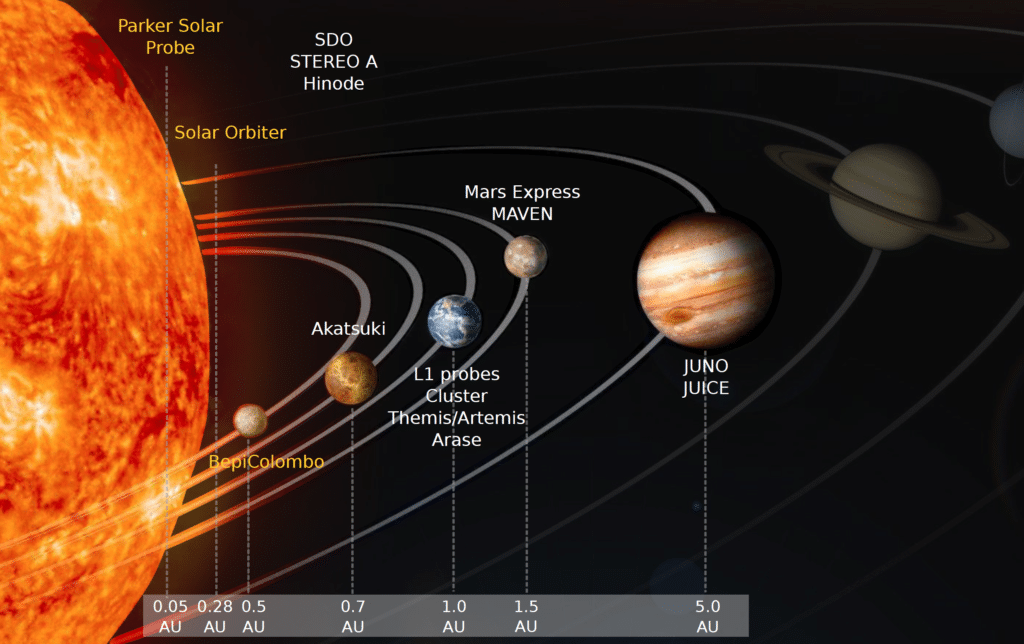

Solar wind is very turbulent. Among other things, my work involves studying the properties of the turbulence of this wind around Earth, but also around other planets, like Saturn and Mercury. The Earth is one astronomical unit (AU = 150 000 000 km) from the Sun, whereas Saturn is much further away, at 10 AUs. By analysing ‘in situ’ wave and particle data (ion density and temperature, electrons, magnetic and electric fields) from instruments on board the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Cluster probe orbiting Earth and the US space agency’s (NASA) Cassini probe around Saturn, my colleagues and I were able to study and compare the properties of the solar wind’s turbulence at these different distances.

The Plasma Physics Laboratory is involved in two other recent solar missionsLe laboratoire de physique des plasmas (LPP)est impliqué dans deux autres missions solaires récentes]. The first, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe (PSP), was launched in 2018 and made measurements of the Sun at an extremely close distance of just 24 million km. PSP continues to edge closer to the Sun and, as its orbit shrinks, it will eventually reach a perihelion distance of just 6.16 million km in 2024–25 (a few hundredths of the distance from the Earth to the Sun), where it will experience temperatures of nearly 1400°C. It will be the first space mission to penetrate the Sun’s atmosphere. The second mission is ESA’s Solar Orbiter, launched in 2020. This probe will get as close as 42 million km to the Sun and explore its off-ecliptic regions (30° latitude) that have never been observed before and measure its electromagnetic environment.

The first results from PSP show bizarre magnetic field reversals in the radial direction, called ‘switchbacks’, accompanied by, a yet unexplained, spontaneous increase in the solar wind speed. How particles are accelerated in the solar wind and what role the heating of the solar corona (the Sun’s million-degree hot upper atmosphere) plays remain great mysteries and PSP will certainly help to shed more light on these. Turbulence is one of the physical processes that could explain the heating of the solar corona and the solar wind.

Analysing data from Saturn and Mercury

In addition to studying the properties of turbulence in the solar wind and planetary ‘magnetogaines’ (the interfacial zones between the solar wind and the magnetosphere), we were involved in the final phase of NASA’s Cassini mission, when the satellite crossed the space between the planet Saturn and its rings2. Cassini made 23 orbits across the plane of the rings, passing inside the innermost D ring for the first time. Each week, we received data from the Langmuir probe on board the satellite that allowed us to determine the electron density of Saturn’s ionosphere (the outer layer of its atmosphere). Not only were we able to characterise this ionosphere in detail for the first time, we also measured dust grains as well as organic matter that had fallen directly from the D ring into the planet’s atmosphere3.

We are also involved in the BepiColombo mission, a joint ESA and JAXA (Japanese Space Agency) mission, launched in 2018 to explore the ionic composition, atmosphere and magnetosphere, as well as the history of Mercury and its geophysics. BepiColombo is a coupled system: a planetary orbiter (the Mercury Planetary Orbiter provided by ESA); and a magnetospheric orbiter (the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, provided by JAXA).

LPP provided two instruments for this mission: a mass spectrometer (MSA), which measures the ionic composition in Mercury’s magnetosphere, and a Dual Band Induction Magnetometer (DB-SC), or Search Coil, which measures the high-frequency (1Hz-640kHz) magnetic field of the planet. The two satellites of BepiColombo, currently in cruise phase, will enter final orbit around Mercury in December 2025.

On 10 August 2021 BepiColombo flew for the second and last time over the planet Venus, and on 1 October 2021 for the first time over the planet Mercury, to benefit from a gravitational assist that bent its trajectory towards the interior of the Solar System. Many of the instruments onboard were active during these flybys, providing unique data on the environment of Venus and Mercury, including their interaction with the solar wind. In particular, the MSA ion spectrometer and the DBSC magnetometers at LPP collected scientific data in space for the very first time. We are currently analysing these data. On the other hand, in addition to the measurements made during the planetary flybys, some of the instruments on board BepiColombo will be operational in the solar wind. Indeed, I coordinated a working group to define strategies for multi-point observations, that is, joint observations between BepiColombo, Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe satellites when the three are radially or magnetically aligned in the solar wind4. A first!