Weather forecasting is now a common practice for which meteorologists require atmospheric simulation models. Météo-France regularly reinforces its intensive computing capacities, quality of numerical weather prediction models, and the use of observation data to calibrate them.

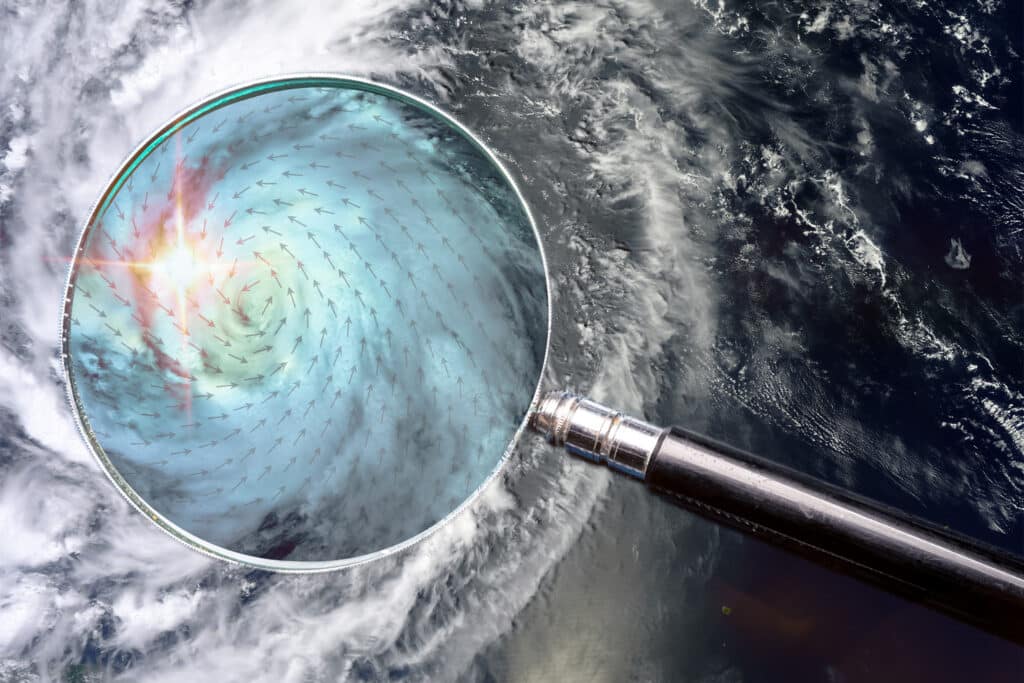

The research carried out at CNRM (Centre national de recherches météorologiques), in collaboration with several national and international partners, focuses on understanding the atmospheric environment and its interactions with continental and oceanic surfaces. The CNRM develops investigative tools for observing and improving our understanding of processes at observation sites. It also works to develop models for numerical simulations our ever-changing atmosphere and its interfaces, doing so on a scale of hours, days or much longer. These models operate on multiple spatial scales, from several tens of metres to hundreds of kilometres – or even on a global scale.

Arome and Arpège

These weather models are used to forecast the weather and study climate change through climate projections. There are several modelling tools, such as Arpège and Arome. Arpège is used to simulate the atmosphere of the entire planet, covering Europe with a mesh size of around 5 km and the rest of the globe with mesh sizes ranging from 5–24 km. Arome covers a domain limited to metropolitan France and neighbouring countries with a horizontal resolution of 1.3 km, and is also deployed over overseas regions.

Arome has been designed to operate over a part of the world only, which may be centred on some overseas territories and other locations of interest. The model is used to improve the short-term forecasting of hazardous phenomena such as heavy Mediterranean rainfall (‘Mediterranean episodes’), severe thunderstorms, fog or urban heat islands during heat waves. It allows simulations to be carried out with very fine resolution, by slicing the atmosphere into small cubes (known as ‘meshes’) to solve the equations governing the physical processes in the atmosphere and at the interfaces.

The emergence of artificial intelligence

The raw results of these simulations must be processed to produce forecasts in an operational framework. In this context, CNRM is increasingly using advanced statistical methods, including artificial intelligence (AI), to combine past forecasts with what has been observed, to somehow adjust the models so that they are as relevant as possible to the observations.

AI is a methodological tool that has been emerging for several years. It can speed up the execution of a weather model and thus reduce its computational cost. For example, one of the most expensive aspects of model execution is solving the complex equations that govern radiative transfer through the atmosphere, through clouds, and the interactions of light rays with the land or ocean surface. Future research could speed up model execution by substituting some explicit resolutions of the physical equations with results obtained through machine learning. Some work goes so far as to suggest the outright replacement of forecasting models solving physical equations with deep learning emulation of forecasting systems.

Another application of AI is the post-processing of modelling results for weather forecasts. This process allows the correction of certain systematic errors in the output of the models to make the forecast more consistent with observations in similar circumstances. It also makes it possible to detect structures corresponding to phenomena at stake, which is all the more difficult as forecasts are increasingly made within the framework of ensemble forecasts, making it possible to better account for the uncertainties of the forecasts. Among the work in progress at the CNRM, we should mention, for example, work aimed at improving the detection of particularly violent thunderstorms in the results of numerical simulations, which are extremely important phenomena to detect but difficult to forecast1.

More innovation, more knowledge

One approach to producing increasingly rich weather forecasts is to reduce the spatial scale on which they operate, thereby representing physical processes that can be solved on a smaller scale. As mentioned earlier, the Arome forecast system, for example, currently operates at a horizontal resolution of 1.3 km. A higher resolution would allow even smaller scale processes to be represented, for example those leading to very localised high-impact thunderstorms. However, a high-resolution model does not guarantee that the location of the most intense thunderstorms can be accurately identified. Thunderstorms are scattered phenomena, not widespread events over large parts of the territory, as are heat waves, and are therefore more difficult to predict in terms of their occurrence, location, and intensity. Observations play a fundamental role in initializing weather forecasting systems, with methods known as ‘data assimilation’.

Work is underway to exploit more innovative observations such as so-called ‘opportunity’ data, collected by participatory tools such as individual connected weather stations. These data are collected by the company that markets these instruments and allow us to enrich our knowledge even if the intrinsic quality is not at the same level as that of the conventional network.

There are also developments in the observations obtained from aircraft and ships, as well as from balloons, equipped with probes, which are sent into the atmosphere several times a day. And then, of course, we have many observations made by satellites, either geostationary or defiling, which provide a view on very large spatial scales. The former provides us with a permanent view of the face of the Earth that concerns us with infrared sensors, for example. The latter circle the Earth several times a day and provide observations along their trajectories with more detailed observations. Scientific and technological advances make it possible to distinguish smaller and smaller meteorological objects from space, which is crucial for characterising the state of the atmosphere and improving forecasts of its evolution.

Interview by Isabelle Dumé

Further reading:

- Mounier, A., et al., Detection of Bow Echoes in Kilometer-Scale Forecasts Using a Convolutional Neural Network, Artificial Intelligence for the Earth Systems, 1(2), e210010. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/aies/1/2/AIES-D-21–0010.1.xml, 2022.

- Rapport Recherche 2021 de Météo-France qui fait référence à plusieurs travaux récents au CNRM sur les modèles de prévision météorologique : http://www.umr-cnrm.fr/IMG/pdf/r_r_2021-fr_web.pdf