Why are cyber attackers targeting supply chains?

- The number of phishing attacks tripled between 2020 and 2021, reaching a record high in 2023, when the Anti-Phishing Working Group recorded nearly 5 million attacks.

- Attacks on the digital supply chain represent a real threat to IT security.

- They can exploit an organisation’s network of partners to target it, thus multiplying the possible attack surface.

- Developers frequently use pieces of code that are freely available on the Internet, allowing hackers to exploit software vulnerabilities.

- To counter this, ethical hackers carry out voluntary intrusions to identify network and infrastructure vulnerabilities in general.

Some reflexes are starting to kick in. An email offers us a suspicious link redirecting us to a page where we have to fill in our login details? We smell the trap of a phishing attack, and we don’t click. An SMS to change the delivery address of a parcel? Deleted before it’s even been read! However, this has not prevented the number of phishing attacks from tripling between 2020 and 20211, until the record year of 2023 when the APWG (Anti-Phishing Working Group) recorded “almost 5 million attacks”.

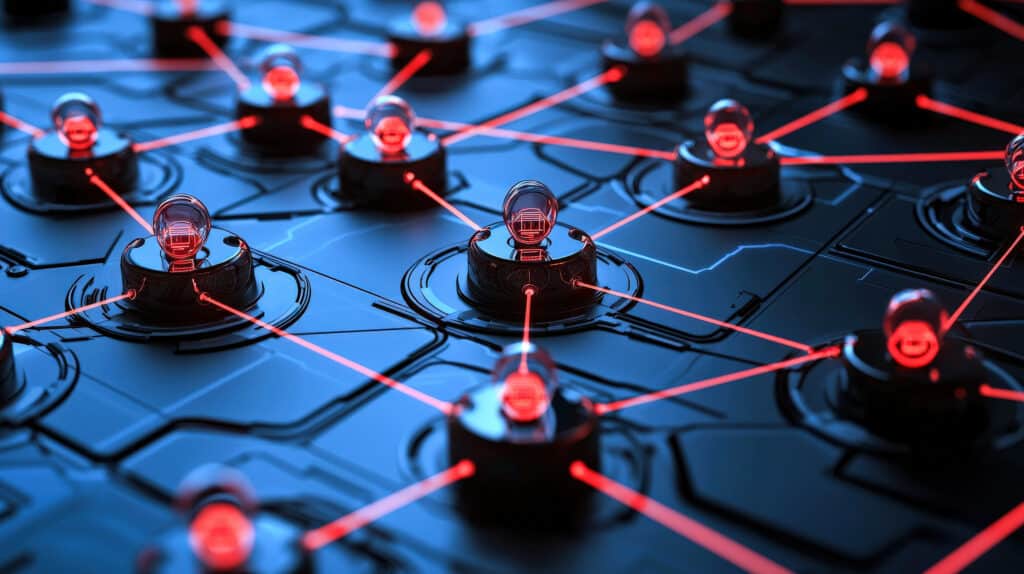

However, this is not the most worrying aspect. Because while cybercriminals continue to exploit human weaknesses to gain access to bank accounts or sensitive company data, another threat is looming in the shadows, still largely unknown to the general public: attacks on the digital supply chain (DSC).

Industry 4.0

Instead of targeting an organisation through a single individual, it is now more common to use the organisation’s network of partners. “It is difficult to attack a company like Airbus head-on, for example,” explains Badis Hammi, cybersecurity researcher and lecturer at IP Paris. “But it is possible to target a smaller service provider that is vital to the company, such as Rolls-Royce, which manufactures engines for Airbus aircraft.” These service companies are in fact integrated into a digital fabric that overlaps the classic production chain (suppliers, factories, distributors, sellers, consumers, etc.): this is the famous digital supply chain. Ransomware in one of the links in this chain is enough to paralyse the multinational that coordinates the whole process. But the danger goes even further.

“In today’s Industry 4.0, everything is connected and can be managed remotely via the Internet. For example, the robotic arms that build cars… This considerably increases the potential cyberattack surface! One virus on a machine’s software, and the factory comes to a standstill,” explains the researcher. But what makes this software so vulnerable?

Open-source building blocks

To understand this, we need to go back to computer code. Developers frequently use pieces of code that are freely available on the Internet. “There are open-source libraries where you can import the code, equivalent to copy and pasting it,” explains Badis Hammi2. These “building blocks” are then assembled together to build the platform, or the software adapted to the company. “The great advantage of open source is that it can be verified by the online community, which is very attentive,” the researcher warns. “But this also means that vulnerabilities can creep in.”

Vulnerabilities or backdoors that allow hackers to access the data circulating in the software. This is the nightmare scenario experienced in 2020 by thousands of organisations around the world, victims of one of the biggest cyberattacks on the software supply chain: the SolarWinds attack3. In September 2019, hackers injected malicious code (called Sunburst) into the Orion software developed by SolarWinds. Then they patiently waited for the American company to offer the Orion update to their customers… unknowingly containing the corrupted code. Nearly 18,000 organisations worldwide were affected, including the US federal government itself, as Orion software is used in institutions such as the Pentagon, the armed forces, various ministries and the FBI.

Spotting the backdoors

This malicious code did indeed contain a backdoor, in direct communication with the hackers’ servers. “If we use the metaphor of a parcel, it’s as if the delivery truck had been hijacked or, worse still, the contents of the parcel had been changed into something malicious,” explains Roni Carta, ethical hacker and co-founder of Lupin & Holmes, which offers cybersecurity solutions for the software supply chain.

“Where it gets complex is that open-source code can use other open source codes. So, you have to imagine a spider’s web of possible entry points for hackers,” adds Roni Carta, whose job is essentially to detect these flaws before they fall into the wrong hands. “Sometimes, hacking is simply done by stealing access to the developers’ own accounts. For example, those who make their code bricks accessible in open-source libraries. It happened very recently, and the owner was warned that his account was vulnerable.”

So how can you protect yourself from attacks? By practising how to thwart them. “Nowadays, we finally teach “ethical hacking”, what is known as the “red team”,” states Badis Hammi. “These are “pentesters”, people who deliberately carry out intrusions to find flaws in networks and infrastructures in general.” Roni Carta is trying to automate this work by creating Dépi, a software programme for detecting flaws in the software supply chain, intended for companies. For Badis Hammi, it is above all necessary to keep an eye on things and keep in mind that for every thousand lines of code or so, there is a potential flaw. In short, we have not finished developing our good cybersecurity reflexes.