Why we need ‘explainable’ AI

The more AI algorithms spread, the more their opacity raises questions. In the Facebook files, Frances Haugen, a specialist in algorithmic rankings, took internal documents with her when she left the company and sent them to the American regulatory agency and Congress. In doing so, she claims to reveal an algorithmic system that has become so complex that it is beyond the control of the very engineers who developed it. While the role of the social network in the propagation of dangerous content and fake news is worrying, the inability of its engineers, who are among the best in the world in their field, to understand how their creation works is questionable. The case once again puts the spotlight on the problems posed by the (in)explainability of these algorithms that proliferate in many industries.

Understanding “opaque algorithms”

The opacity of algorithms does not concern all AIs. Rather, it is especially characteristic of so-called learning algorithms known as machine learning, particularly deep learning algorithms such as neural networks. However, given the growing importance of these algorithms in our societies, it is not surprising that the concern for their explainability – our ability to understand how they work – is mobilising regulators and ethics committees.

How can we trust the systems to which we are going to entrust our lives? For example, AI may soon be driving our vehicles or diagnosing a serious illness. And, more broadly, the future of our societies through the information that circulates, the political ideas that are propagated, the discrimination that lurks? How can we attribute responsibility for an accident or a harmful side effect if it is not possible to open the ‘black box’ that is an AI algorithm?

Within the organisations that develop and use these opaque algorithms, this quest for explainability basically intertwines two issues, which it is useful to distinguish. On the one hand, it is a question of explaining AI so that we may understand it (i.e. interpretability), with the aim of improving the algorithm, perfecting its robustness and foreseeing its flaws. On the other hand, we are looking to explain AI in order to identify who is accountable for the functioning of the system to the many stakeholders, both external (regulators, users, partners) and internal to the organisation (managers, project leaders). This accountability is crucial so that responsibility for the effects – good or not so good – of these systems can be attributed and assumed by the right person(s).

Opening the “black box”

A whole field of research is therefore developing today to try to meet the technical challenge of opening the ‘black box’ of these algorithms: Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). But is it enough to make these systems transparent to meet the dual challenge of explainability: interpretability and accountability? In our discipline, management sciences, work is being done on the limits of transparency. We studied the way in which individuals within organisations take hold1 of the explanatory tools that have been developed2, such as heat maps, as well as performance curves, often associated with algorithms. We have sought to understand the way organisations use them.

Indeed, these two types of tools seem to be in the process of being standardised to respond to the pressure from regulators to explain algorithms; as illustrated by article L4001‑3 of the public health code: « III… The designers of an algorithmic treatment… ensure that its operation is explainable for users » (law no. 2021–1017 of 2 August 2021). Our initial results highlight the tensions that arise within organisations around these tools. Let us take two typical examples.

Example #1: Explaining reasoning behind a particular decision

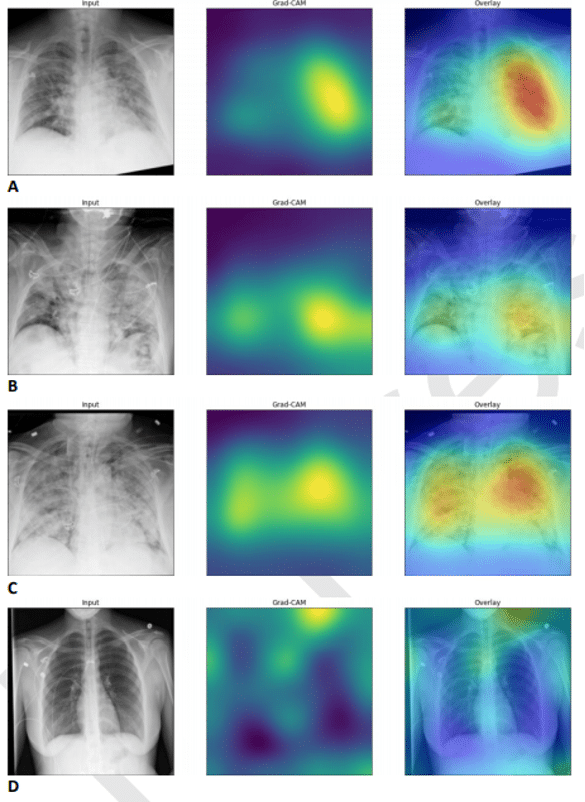

The first example illustrates the ambiguities of these tools when by business experts who are not familiar with how they work. Figure 1, taken from Whebe et al (2021), shows heat maps used to explain the operation of an algorithm developed to detect Covid-19 from lung x‑rays. This system performs very well in tests, comparable to, and often better than, that of a human radiologist. Studying these images, we note that in cases A, B, and C, these heat maps tell us that the AI was pronounced from an area corresponding to the lungs. In case D, however, the illuminated area is located around the patient’s collarbone.

This observation highlights a problem often found in our study of the use of these tools in organisations: designed by developers to spot inadequate AI reasoning, these tools are often, in practice, used to make judgements about the validity of a particular case. However, these heat maps are not designed for this purpose, and for an end user it is not the same thing to say: “this AI’s diagnosis seems accurate” or “the process by which it goes about determining its diagnosis seems valid.”

Two problems are then highlighted: firstly, there is the question of training users, not only in AI, but also in the workings of these explanatory tools. And more fundamentally, this example raises questions about the use of these tools in assigning responsibility for a decision: by disseminating them, there is a risk of leading users to take responsibility on the basis of tools that being used for decisions other than their intended purpose. In other words, these tools, created for interpretability, risk being used in situations where accountability is at stake.

Example #2: Explaining or evaluating performance

A second example illustrates effects of organisational games played around explanatory tools such as performance curves. For example, a developer working in the Internet advertising sector told us that, in his field, if the performance of the algorithm did not reach more than 95%, customers would not buy the solution. This standard had concrete effects on the innovation process: it led her company, under pressure from the sales force, to choose to commercialise and focus its R&D efforts on a very efficient but not very explainable algorithm. In doing so, she abandoned the development of another, more explainable, but not as powerful algorithm.

The problem was that the algorithm they chose to commercialise was not capable of handling radical changes in consumer habits, such as during Black Friday. This caused the company not to recommend customers to engage in any marketing campaigns at this time, as it was difficult to recognise that the algorithm’s performance was falling. Again, the tool is misused: instead of being used as one element among others to make the choice of the best algorithm for a given activity, these performance curves were used by buyers to justify the choice of a provider against an industry standard, In other words: for accountability.

The “man-machine-organisation” interaction

For us, researchers in management sciences, interested in the processes of decision-making and innovation, the role of tools to support them, and the way in which actors legitimise the choices they make within their organisations, these two examples show that it is not enough to look at these computational tools in isolation. They call for an approach to algorithms and their human, organisational and institutional contexts as assemblages. Holding such an assemblage accountable then requires not just seeing inside one of its components as the algorithm – a difficult and necessary task – but understanding how the assemblage functions as a system, composed of machines, humans, and organisation. And, consequently, to be wary of a too rapid standardisation of explicability tools, which would result in man-machine-organisational game systems, in which the imperative to be accountable would replace that of interpreting, multiplying black boxes of which explicability would only be a façade.