Green swans : a tipping point for global finance

- Inspired by the “black swan,” a concept referring to rare, unpredictable events with an extreme impact, the “green swan” refers to events due to climate change, which we know with certainty will occur more and more often in the future.

- The green swan concept emerged through discussions in central banking networks, concerned with the financial instability that could arise from such repeated and intertwined climate-related events.

- What can supervisors and regulators do to reduce these risks? Beyond voicing their concerns, tools such as asset classification can accelerate the energy transition.

- But as powerful as central bankers’ ability to direct financial flows may be, the most decisive tools, notably the price of carbon, remain in the hands of governments.

- The major challenge today is coordination between institutional players whose responsibilities and constraints do not align.

Where does the concept of the green swan come from, and how did it come about ?

The concept emerged within the Bank for International Settlements, an institution whose mandate includes coordination between central banks and therefore financial stability. We took inspiration from “black swan,” a notion developed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, which evokes the extreme impact of certain types of rare and unpredictable events. Taleb’s book was published in 2007, just before the financial crisis that came as an illustration of his idea.

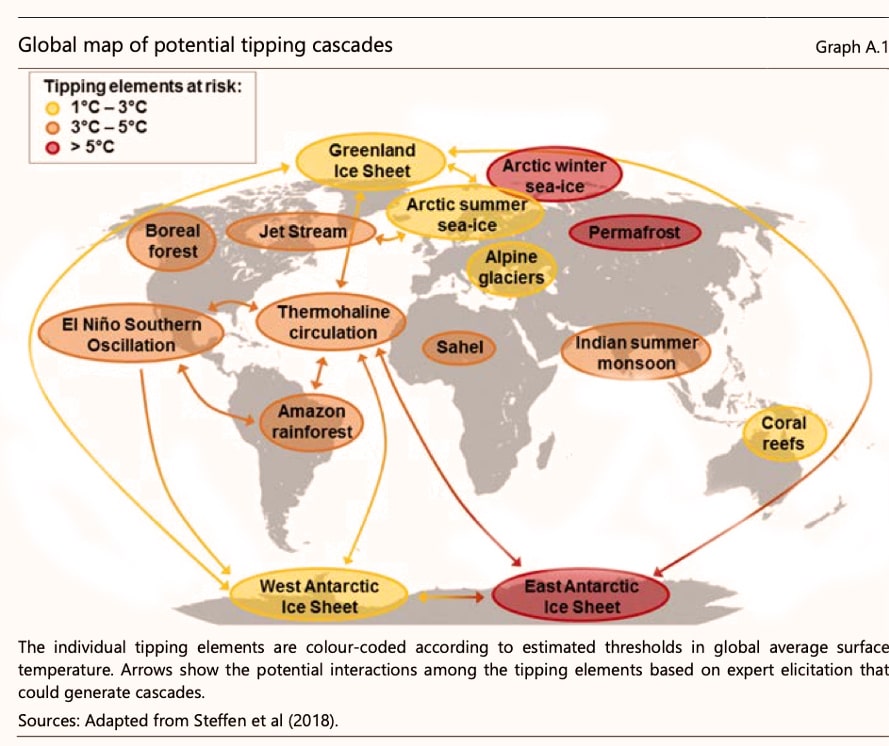

For Taleb, although events of this type do sometimes occur, their probability remains low. They are confined to the tail of the distribution of a fairly classical Gaussian probabilistic universe. The idea of “green swans”, however, is an epistemological break from this distribution because climate change is turning the tables. We now know with certainty that extreme impact events will occur in the coming decades. We also know, and this is quite worrying, that if we do nothing to reverse the course of this evolution, points of no return will be reached, with intertwined consequences. For example, rising sea levels will directly affect many coastal urban areas, with cascading consequences : some will become uninhabitable, others will require huge investments, property prices will suffer shocks, and insurance costs will increase. Similarly, the intertropical zone could become uninhabitable if days of over 45°C become permanent rather than exceptional. Here again, the demographic, economic and political consequences are intertwined and can become very difficult to manage : one crisis leads to another, and so on. Just as in 2008 the very sharp correction in the US property market degenerated into a banking crisis, then a global financial crisis, then a euro crisis, then a political crisis with the rise of populism.

This brings us to the idea of the “green swan”: events with extreme impact will occur, whose consequences will intertwine as they become more frequent.

This epistemological reversal of the black swan model directly challenges the community of financial supervisors and regulators. Within the area of central banking, how do you get a hold on these emerging risks ?

At the BIS, we have sculpted this debate through the lens of financial stability, because that is the core of our mandate. To put it simply : these events produce losses on the balance sheets of financial institutions (banks, insurance companies, pension funds). These potentially huge losses are sometimes uninsured. Financial institutions are not yet able to absorb them (notably because they do not have enough equity). There is therefore a risk of crisis.

Other players in our field have taken this thinking a step further, by looking at price stability : for example, drought affects agricultural productivity and thus causes inflation.

There is a third level of thinking : “transition risks.” When we start to consider new constraints, in this case CO2 emissions, we must acknowledge that implementing new regulations might lead to a whole series of shocks : some industries’ value will increase, other industries’ value will decrease, some may even disappear or see their economic model dramatically disrupted. These shocks will result in changes in the banks’ balance sheets. A simple change in regulations can cause a sharp decline in the value of certain assets. It is possible to anticipate this effect – the oil companies, for instance, are working on it. But still, a mass sale of their shares would influence financial stability.

We are not talking here about “simple” financial crises, which are traditionally the domain of central banks ; we are talking about something else.

Fourth level of reflection : asset classification, with the risk of misclassification. A transition policy requires a reorientation of investment flows towards certain activities. Classification is thus a powerful tool, since they guide massive investments. But some classifications are not precise enough as they mix various criteria. This makes it difficult for investors to discern and make the right moves. One example is ESG (environmental, social and governance) criteria. Yet classifications guide massive quantities of investments. Eventually, very precise criteria will be needed to avoid greenwashing. In particular it should be mandatory for each and every company to precisely assess and disclose its carbon footprint, along with its strategy to get closer to carbon neutrality. It is the role of supervisors and regulators to ensure that this information is increasingly available and granular. At the BIS, we have started to build portfolio models.

The question of classifications and new criteria has given rise to an unresolved debate within central banking circles : how should central banks take these new criteria into account when they buy back assets, or when they accept collateral ? Central banks cannot do everything, but they do play a crucial role in financial stability and their instruments are so powerful that they will play a role in the energy transition. Nonetheless the main instrument of the transition, setting a price for carbon, is out of their reach : such responsibility belongs to governments. Some central bankers consider that it is their duty to act since governments are not doing enough, while others point to the risk of moral hazard : if central banks decide to act, governments will do even less.

However powerful the institutions in charge of financial stability may be, and however advanced they may be in understanding new risks, they cannot act alone. They cannot substitute for policy ; in fact, the opposite is true. We are not talking here about “simple” financial crises, which are traditionally the domain of central banks ; we are talking about something else.

No single actor will be able to provide the answer. The first challenge for action is coordination, which brings us directly back to the work of Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom on the governance of the commons. We need to get our act together, to set an organization so that science can play a role. Here I shall add an essential point : we must act as if there will be no alternative technology and ensure that the cost of insurance is available.

A key challenge, though, is to develop and disseminate the technologies that will enable us to achieve carbon neutrality.

Indeed. And this concerns both private and public investments. We need to mobilize public capital and not just direct private capital flows. Alliances will also be needed. These have begun to develop – think of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, which was launched in 2021 and brings together financial institutions, or the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a network of more than 100 central banks and financial supervisors that aims to accelerate the scaling up of green finance and to develop recommendations on the role of central banks in climate change.

We must act as if there will be no alternative technology and ensure that the cost of insurance is available.

The role of these alliances is to push for a change in practices and the implementation of new instruments, but also to discuss them. This forum format is essential to bring out problematic aspects, for it is a crucial issue to imagine the unimaginable. The NGFS has made a point of developing “discordant” scenarios, including the “disorderly transition”: the situation keeps deteriorating and adjustments are made too late, with every investor rushing to sell their “brown” assets. In this scenario, serial bankruptcies lead to a financial crisis. The reflection is therefore on how to start an orderly transition, with a form of ecological planning and coordination of actors.

The current rise in energy prices drives us in the right direction, but it also reminds us of the importance of redistributive policies, since some social groups are particularly exposed to energy price increases. Nevertheless, the current shock is an opportunity that should be seized : how can we use this change in relative price as an incentive to accelerate the transition ?

If we want to seriously address these issues, all players involved need to work together and consider the different dimensions of the transition. Such coordination is far from easy, since it implies a combination of long and short cycles. The short cycles of politics, particularly, might arise the “tragedy of the horizon.” And we should not forget the “tragedy of commons,” with the risk of free riders leaving the efforts to others.

Finally, at the global level, international coordination inevitably requires support from the most advanced countries, either through technology transfer or via an investment fund. The last COP resulted in the promise of a $100 billion fund, but it is too little.

Interview by Richard Robert