Public district heating systems are collective heating infrastructures, owned by local public authorities. They distribute heat from production units (e.g., centralised boilers, geothermal plants, prosumers) to connected buildings (e.g., hospitals, social housings, individual houses) through a fluid – usually overheated water. The supply mix and consumer profiles vary a lot from one country to another, depending on the available resources and the energy density of the area, for example. If district heating is still heavily based on fossil fuels in the EU, more and more renewable and waste heat sources are being integrated to the supply mix making it a great lever for the energy transition1.

#1 Public district heating faces environmental and societal challenges

Going for a carbon-neutral district heating system requires a change in means of heat production from fossil-intensive to decarbonised methods. However, decarbonisation can take many roads. There is no clear solution that optimal in every context. Finding the most environmentally-friendly solution often requires using local resources, a variety of heat sources to and coordination of multiple local actors (most of which are not professionals in the heating market). Securing local resources (like waste heat from local industrials, or biomass resources) is a challenge that must be overcome to engage long-term investments. Several European projects have tackled this precise problem, trying to propose mechanisms and contract clauses to secure local resources and unlock investment potential2. Some public authorities – for instance in Dunkirk – also play a role in facilitating such partnerships, by providing insurances to industrials (production outlet, etc.).

Another uncertainty comes from the framing of “sustainable” district heating. It can vary depending on political decisions. Some countries like Denmark have already made a shift from carbon-intensive heat sources to biomass boilers, pushed by policy incentives. These new infrastructures have a lifespan of several decades, but their financial balance is threatened. As sustainability of biomass is increasingly considered problematic at a political level, incentives and subsidies may be re-assigned to a other technologies. Similarly, the outcomes of the European taxonomy can impact the investments capacity in some technologies.

All in all, shifting to a sustainable district heating requires long-term investments. But there is a high level of uncertainty about what would be the best investment for today and tomorrow, and a lack of know-how on securing local resources in long-term projects.These long-term investments and the overall design of the infrastructure make district heating systems more of a monopoly; there are rarely several district heating operators in the same area, meaning that unlike other energy infrastructures, you cannot change your subscription from one operator to another. This lock-in effect can be seen as a burden by the final consumer, all the more as they are usually not the subscribers. In France, district heating systems connect buildings, not individual housings. The principal interlocutor of the network’s operator is thus the building owner, not the final heat user. This means that the final user has very little power over heat delivery: the user cannot choose the operator (who is appointed by the public authority – like the municipality – based on a public tender), in some cases he cannot choose whether or not the building is connected to the network (in particular for social housing), and if there are no individual meters he does not have the means to optimise the heating level of his housing, which is mostly controlled at a building-level. Finally, when paying for the heat, the final user often receives a bill from the building-owner, which will comprise “heat and other charges”, making it hard to understand heat tariffication and his means of action to lower his bill.

Further amplifying this issue, multiple actors are involved in district heating systems, making it difficult to navigate shared responsibilities and creating some opacity in communication. For instance, in the case of a default in the heat delivery for an apartment in a social housing, the issue can come from the global district heating system. The responsibility is thus shared between the public authority and the network operator, depending on the type of contract governing the network operations. The problem may also come from the maintenance of the building heating system. In this case, responsibility is shared between the building owner and the company in charge of the maintenance of this secondary network. Heat delivery issues can also be cause by a lack of insulation, the latter being the responsibility of the building owner. Communication between all these actors is not always fully optimized. For example, the 2021 report from the General Accounting Office highlights the lack of transparency on district heating governance – especially in cases of Public Service Delegation in the form of concessions – leading the public authority owning the network to have limited control over their own public service 3.

#2 Co-creation can help unlock the development of sustainable district heating

Co-creation is a collaborative process between local stakeholders to find innovative solutions to public stakes4. It allows integration of a variety of stakeholders in the design and operation of the network, who would otherwise be stuck in pre-defined roles with no part in the governance of the network (customers, citizens associations, etc.).

Due to its inherent collaborative and open approach, co-creation is aligned to a global dynamic of municipalities and public authorities reclaiming control over their public services for which operation has long been delegated to private operators. District heating systems are now part of the strategic planning of public authorities, who come with new demands towards these operators – like carbon-neutrality, communication with citizens, etc. – and wish to be involved more closely in the governance of the network.

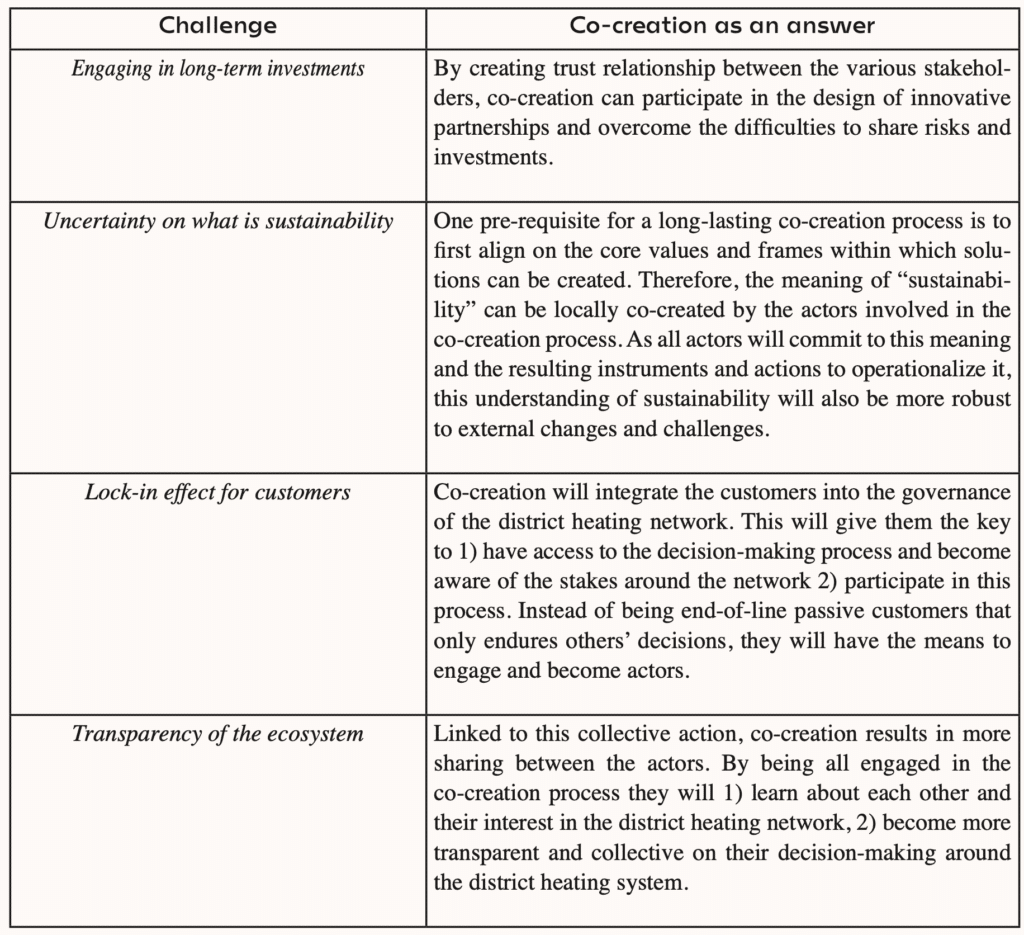

By being integrated to the whole lifecycle of the infrastructure – or at least to its contract for operation – co-creation can foster its development by answering to the above-mentioned challenges (Table 1).

#3 Several aspects must be taken into account when designing a co-creation approach

Co-creation requires a sustained endeavour during the whole infrastructure lifespan. As any relational process, resources must be engaged in the long-term to ensure the success of the process. Here are four principles that can facilitate the integration of co-creation into a district heating project.

Engaging with the stakeholders: One prerequisite to engage in a co-creation process is to take time understanding the territory. Co-creation emerges from common needs and stakes. Therefore, getting a strong sense of the main local stakes, and the existing dynamic in tackling them is necessary to craft a relevant co-creation process. This first step can also be a way to get to know the local actors if you are not familiar with the ecosystem. One interesting aspect when getting this first sense of the territory, is to look at the existing methods used for e.g., local democracy, communication, and participation. The more the co-creation process relies on the existing, the easier it would be to get people to commit to go a little bit further in their approach.

Sustaining co-creation through governance: To integrate co-creation as well as possible (not only in reaction to crisis) there is a need for a long-term engagement strategy. Usually, stakeholders realise that co-creation can be interesting only when they are faced with a crisis. However, crisis is not the best time to engage in a co-creation process, as people are polarised around a specific issue. Integrating co-creation from the very design of projects, when everyone is committed to work together in solving a common issue, is usually much easier. However, to keep this dynamic ongoing and efficient when there are crises, this co-creation process could be embedded within governance arrangements. These arrangements frame the roles of stakeholders, their perimeter of influence and the decision-making process. They can be embodied through a variety of engagements formats, designed for different moments of the project lifecycle, stakes and their corresponding stakeholders.

Securing the needed resources: Both internally (to the participating organisations) and externally to create some commitment to these resources and cultural shift. Co-creating requires some specific resources and competencies, that are different from the technical or commercial ones at the heart of the project teams on district heating. Engaging on long term co-creation processes means to secure some resources internally to the participating organization – e.g., people participating in the co-creation process, but also the support teams to make the decided actions real – and externally by securing the commitment of the targeted stakeholders, that may be outside of the usual district heating stakeholders. For instance, when designing co-creation workshops with citizens to design the reconfiguration of a street where district heating will extend, it is important to understand how to incentivize the citizens to come and to keep their engagement on the long run. Finally, co-creation entails a major cultural shift, decentralizing the decision-making and making the public infrastructure more democratic. The importance of this cultural shift, and the need to accompany this shift, should not be minimized if ones want to design a sturdy co-creation process.

Monitoring the impact: A last principle when it comes to co-creation, is to design from the start a monitoring system of both the process itself (who is integrated, what actions have been taken, etc.) and of the ecosystem (should the perimeter of the co-creation process vary? Should new stakeholders be integrated to the co-creation process?). People engaging in co-creation should be accountable for their actions and always strive towards improvement. Co-creation is not an end per se, but a mean for decision-making. These decisions should lead to concrete actions that help solve actual local issues. Also, co-creation is never fully achieved, but always under construction. The process should always be re-adapted, facing the new stakes, new demands, new stakeholder groups, etc. As the collaborative culture spreads, new forms of collaboration may emerge and cause a complete re-design of the co-creation process.