Clean, safe… and “almost unlimited”: on paper, fusion seems to be the ideal source of electricity, with an increasing number of experiments being carried out in the field. In 2024, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) identified more than 20 fusion power plant designs under development, from Canada to China, the United States, Europe, Israel and South Korea. However, the technological obstacles are staggering, as every aspect of this future energy production system poses considerable challenges for researchers, to the extent that experts do not envisage large-scale deployment for at least several decades. This distant and uncertain horizon does not prevent promises from circulating, always supported by a keyword that sounds like a mantra: “unlimited”.

Describing fusion as such highlights its very high energy density – meaning small amounts of fuel can produce very large amounts of electrical energy – and capitalises on the reputation of its fuel as virtually inexhaustible. In reality, it is the fusion of two hydrogen isotopes, deuterium (stable) and tritium (unstable, radioactive), that will produce heat, which is then converted into electricity. While deuterium exists in its natural state, this is not the case for tritium. “It must therefore be produced within the reactor itself from the lithium contained in the walls, through a reaction induced by the neutrons generated by the fusion,” explains Jacques Treiner. The most efficient way to achieve this is to use lithium enriched to 50% in Li‑6 (an isotope present at only 7.5% in natural lithium). Ultimately, a power plant supplying 1GW of electricity will consume 167 kg of deuterium and 7 tonnes of natural lithium annually.

Abundant resources

Deuterium is indeed found in large quantities in nature: there are 33 g per cubic metre of seawater, and it can be extracted using well-established processes. But what about lithium? The US Geological Survey estimates resources at 115 million tonnes, of which 30 million tonnes are currently exploitable reserves. This is more than enough, according to fusion advocates, to consider this fuel “negligible”. In fact, if fusion were the only consumer of this light metal, the reserves would be sufficient to produce 30,000 TWh per year (i.e. the equivalent of global electricity production in 2024, all sources combined) for more than a millennium. The same power produced by coal, natural gas or fission power plants would deplete their fuel reserves in less than a century – or even much less.

But fusion is far from being the only industry that needs lithium. This element is already one of the most consumed resources in the energy transition, particularly to fuel the booming market for electric vehicle batteries. From 95 kt in 2021, global demand for lithium has risen to 205 kt in 2024 and could reach 928 kt in 2040, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Studies have warned of possible supply shortages by the end of the century due to soaring demand, the geographical concentration of resources, price volatility and the limitations of recycling and mining. Admittedly, there is always a high degree of uncertainty surrounding projections of this kind. But competition for lithium remains very real and is likely to continue in the long term. When fusion is ready, there is therefore no guarantee that supply will be easy.

“To highlight the need for long-term resource management strategies, we could put forward the obviously rather naive proposal of deciding to set aside stocks for fusion,” suggests Gérard Bonhomme. “The lithium requirements for fusion are incredibly low compared to those for electric vehicles: we could consider that the considerable benefits it will bring in the future warrant keeping small reserves available for its use.” However, fusion’s current level of development, the foreseeable tensions on the lithium market and the lack of global governance on the light metal are serious obstacles to this option at present.

Scarce resources: a bottleneck?

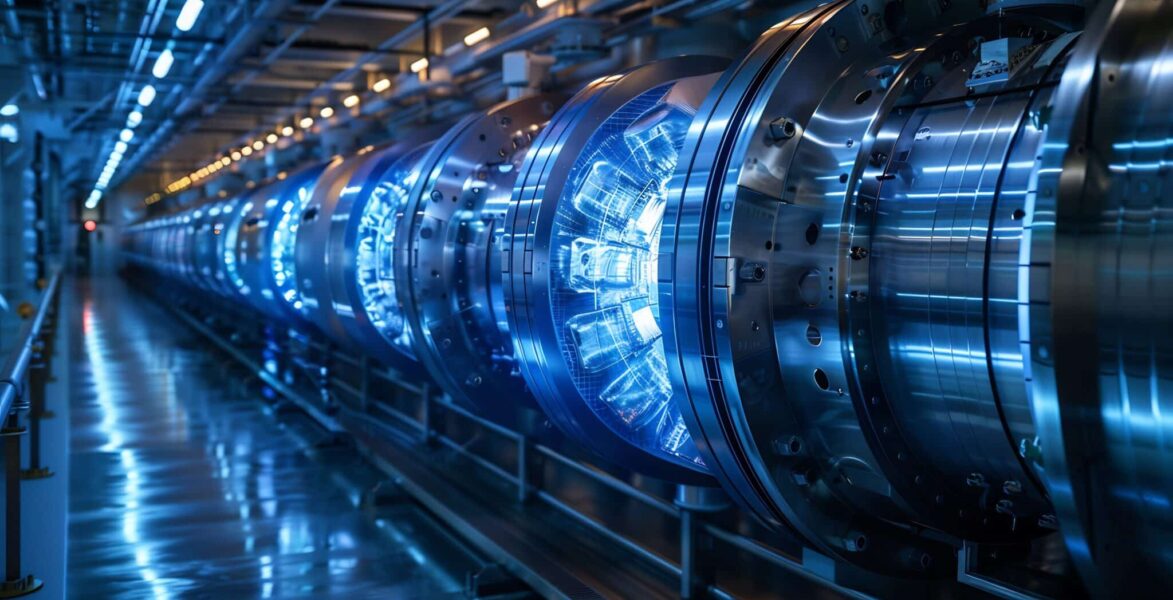

The material requirements of a power plant are not limited to its fuels: they also include all the resources used in production facilities and in distribution and storage infrastructure. The future of fusion will therefore also depend on the ability of research to limit, or even eliminate, the quantities of scarce resources used. This requirement could prove difficult to meet, particularly for technologies used to confine plasma. While ITER1 relies on a magnetic field generated by niobium-tin coils, these resources may be insufficient to build a fleet of thousands of reactors. To date, the best candidates to replace them and ensure the control and large-scale industrial deployment of fusion energy remain high-temperature superconductors. However, the most promising concepts using REBCO2 high-temperature superconductors rely on the use of rare earths, which are included on the lists of critical materials (i.e. essential to the economy and likely to experience supply disruptions) of the European Union and the US Geological Survey. Could other less sensitive candidates emerge? Only time will tell.

The materials associated with containment technologies are far from being the only ones that raise questions.

The materials associated with containment technologies are far from being the only ones that raise questions. “Which ones will be chosen for the walls, which need to withstand intense flows of very high-energy neutrons? How often will they need to be replaced? These problems currently remain unresolved. A dedicated test machine, the International Fusion Materials Irradiation Facility (IFMIF), is to be built to study them,” adds Jacques Treiner.

In comparison, what are the material requirements of other operational power plants? “Fission and fossil fuel power plants consume roughly the same amounts of basic materials (concrete, steel, aluminium and copper) as fusion. But renewables use 10 to 20 times more,” says Jacques Treiner. Renewables also use critical materials, sometimes in significant quantities, such as neodymium in the case of wind power. “Fusion will not be a panacea. But it will be a high-intensity energy source with relatively low impacts on resources. Neither fossil fuels, renewables, nor even second- or third-generation nuclear fission can claim this dual advantage,” summarises Gérard Bonhomme.

Rediscovering limits: a catalyst for action?

Fusion is therefore “promising” and “extremely ambitious”, but not “practically unlimited”. And that’s just as well, because “unlimited energy would lead not to material abundance and infinite growth, but to ever faster depletion of resources,” points out Jacques Treiner. “Relativising or even glossing over the finite nature of the Earth’s resources stems from a desperate desire for ignorance, which is somewhat self-defeating. On the contrary, facing up to its limitations allows us to specify the timescales involved in relation to the climate, energy and water resources, agricultural inputs, the state of biodiversity, etc. This is the condition for restoring the place and meaning of political action.”

For Gérard Bonhomme, however, this must be based on a long-term vision: “Recognising the limits of global resources must encourage us to think about and develop strategies that optimise combinations of solutions with different development timescales, capable of guaranteeing sufficient energy supplies for a human population of ten billion individuals.”