Freight transport: the way out of fossil fuels

- Freight transport is now largely dependent on oil: what are the technological options to get out of this dependence?

- There are five main categories of technological options: switching to electricity, hydrogen, methane, liquid biofuels, or synthetic fuels.

- Each mode of transport has its own technology option, e.g. for heavy goods vehicles, the use of electricity would be effective only for short distances. For longer distances, gas has yet to make its mark.

- Whatever the mode, decarbonisation is likely to be slow, costly, or face major technical and implementation challenges.

- It also depends on resources in tension. It is therefore necessary to prioritise the reduction of energy consumption in freight transport as much as possible.

Freight transport is now largely dependent on fossil fuels, both for global logistics chains and in France. Heavy goods vehicles and light commercial vehicles are mainly diesel-powered. The same is true for river transport boats, while maritime transport runs on heavy fuel oil. Air freight depends on paraffin. Only rail freight has already made a significant shift away from liquid fuels and oil.

To meet the climate challenge, decarbonisation of the sector is essential, but has not yet begun. While the first article in this series pointed out the five levers for decarbonising freight transport (moderation of transport demand, modal shift, vehicle filling, vehicle energy consumption, energy decarbonisation), this one focuses on the last lever of energy decarbonisation. And asks: what are the technological options for moving freight transport away from its dependence on oil?

Decarbonisation options available

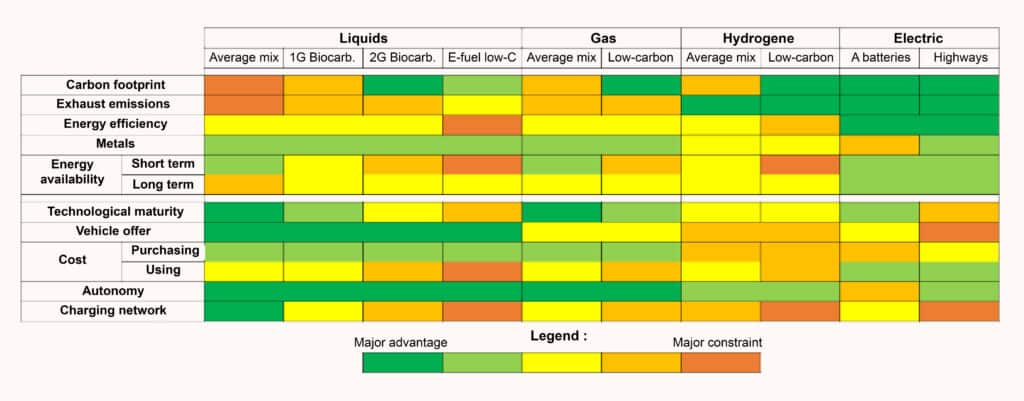

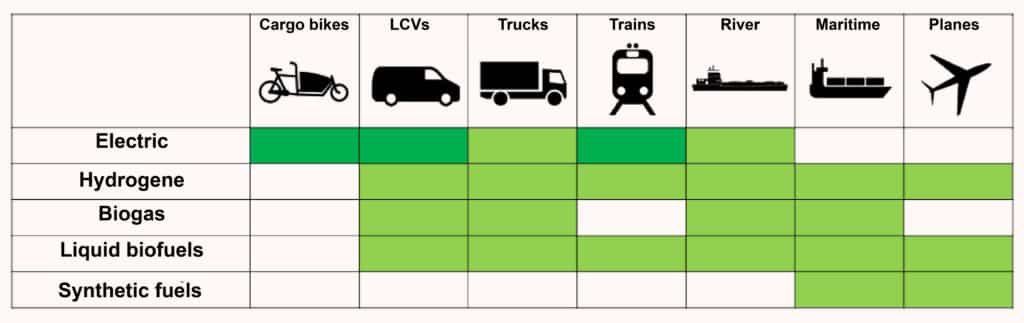

It is possible to give 5 main categories to find your way through the technological options for doing without oil in transport. The first option is to switch to electric, about 90% of which is already low carbon in France1. Electric motors are also more energy efficient than combustion engines, which makes them a preferred option when possible. Because the volume of batteries to be carried makes electrics unthinkable for certain heavy modes, such as air or sea transport (apart from a few niche applications over short distances).

Another option that relates to electric is hydrogen. The main means of low-carbon hydrogen production envisaged is indeed the electrolysis of water, which requires electricity. And in addition to the internal combustion engine option for using hydrogen in the vehicle, the fuel cell option allows the hydrogen to be converted back into electricity for use in an electric motor. The main advantage of hydrogen is that it eliminates the constraints of range and battery recharging, particularly for heavier vehicles. However, hydrogen production is still 95% dependent on fossil fuels, and is a less energy-efficient option than direct electrification, which still presents many technical and economic challenges for its deployment in transport.

Another gas that is often mentioned is methane, also called natural gas for its fossil-derived version, or biogas or renewable gas for the low-carbon-derived versions. Only this biogas is interesting from climate point of view. But, although it is growing rapidly, gas production from biomass methanisation (agricultural effluents, intermediate crops, bio-waste, co-products, or crop residues, etc.) will only account for around 2% of gas consumption in France in 20222. And biogas will only be able to account for a very significant share of gas consumption if there is a sharp drop in the volumes consumed, which today are mainly in the building and industrial sectors.

Liquid biofuels are also produced from biomass. They are more developed and are already incorporated into road fuels, up to a little over 8% in 2022 for diesel3. However, the production of this biodiesel is far from being virtuous to date: more than three quarters of the raw materials used are imported, most of them come from crops that compete with food uses4, and the reductions in CO2 emissions are very limited compared to oil, when all the impacts are considered.

Finally, synthetic fuels (or electrofuels or e‑fuels) are at the interface of several energy carriers already mentioned. They consist of using low-carbon electricity to produce hydrogen, which is combined with CO2 (or nitrogen for e‑ammonia) to make liquid or gaseous fuels5. Their main advantage is that they can replace many of the fuels currently in use, without any modification to vehicles. On the other hand, they suffer from many challenges: their production is only in its infancy, and must be based on very low-carbon electricity in order to present a largely favourable carbon balance; the electricity requirements for their production are very high, in the order of 4–5 times higher for e‑diesels than for direct use in an electric vehicle6; as a result, their cost is also very high, even more so in the short term7.

It is clear from these different options that their current carbon footprint is quite varied, depending on the level of decarbonisation of these different energies or energy carriers. For the moment in France, only electricity is largely decarbonised. Therefore, the levels of deployment, but also the constraints and challenges to be met for their development are varied. This invites us to try to find the most relevant energy mix according to the many issues to be integrated (technical, economic, climatic, resources, etc.).

The example of heavy goods vehicles: how to get out of oil?

Road transport accounts for three quarters of greenhouse gas emissions from goods transport in France (including international transport), with 60% from heavy goods vehicles and 16% from light commercial vehicles. For the latter vehicles and for HGVs operating in the last few kilometres or the shortest distances, electric power should rapidly become the dominant engine. For longer distances, competition is stronger and illustrates a significant conflict between the most environmentally friendly options and the availability of these solutions, particularly in the short term.

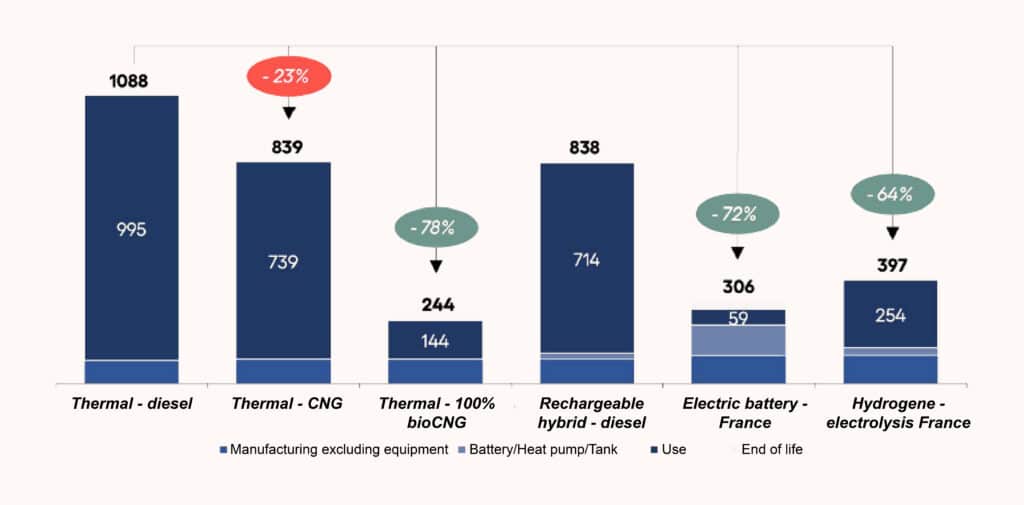

The figure above shows that, as of 2020, three options allow for very significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions for road tractors8. These same options will even achieve reductions in the order of a sixfold reduction for a truck sold in 2030 compared to diesel9.

Sales of gas-fuelled trucks accounted for 4.5% of the market in 2022 for trucks over 7.5 tonnes and represent the leading alternative energy to diesel10, but biogas is only available in limited quantities11. The production of low-carbon hydrogen is only in its infancy and the supply of trucks is not expected to take off strongly before 2030. Finally, the supply of electric trucks is low to date, and they accounted for only 0.3% of truck sales in 2022 in France12.

However, in early 2023, the European Commission proposed a revision of the CO2 emission standards for new heavy goods vehicles, aiming for a 45% reduction in these emissions in 2030 compared to 201913. The main manufacturers already seem to be in line with this objective and are aiming for around 50% of sales of heavy goods vehicles with zero emissions by the end of the decade14. This target will be met mainly by electric vehicles, supplemented by a smaller proportion of hydrogen trucks.

It should be noted that electric vehicles could also be deployed over long distances with the help of electric highways, which allow vehicles to recharge during their use by modifying the infrastructure (electrification by catenary, rail, or induction)15. While these technologies make it possible to reduce the constraints linked to the batteries, their range, and their recharging (high power demands for rapid recharging, pause times, etc.), the choice of the technology to be favoured is still not very mature and deployment would require coordination at European level to be of real interest.

This example also shows the difficulty in choosing the engines and technologies to be preferred. The diversity of decarbonation options is obviously an asset and can help gain resilience according to future constraints. However, no solution is perfect, and it will not necessarily be efficient or even possible to invest in the supply or recharging infrastructure for all decarbonisation options, or for manufacturers to invest in all engines at once. It is possible that one or two options will end up being the most popular for each mode, whether for heavy goods vehicles or for other modes.

Which energies for the other modes?

For the other modes of transport, a mix of different technologies is often mentioned. For inland waterways, conversion to biofuels or biogas is the easiest to envisage from a technical point of view. But hydrogen or even electric power could also play a role in decarbonising this mode, because of the distances or even volumes that are still reasonable to imagine carrying batteries (which are heavy) or hydrogen (which takes up a lot of space).

For maritime transport, gas-powered ships and then converting them to biogas have long been the preferred way of moving away from oil. Sailing ships are also likely to develop, at least as a propulsion aid. There is also increasing talk of synthetic fuels, in particular e‑ammonia or e‑methanol for this mode, which is likely to be particularly long and difficult to decarbonise. The same applies to air transport, where the transition from oil should be based primarily on second-generation biofuels, synthetic paraffin or hydrogen for applications that allow it.

Finally, the railways are already largely electrified, but about 15% of their energy consumption is still based on diesel17. The electrification of lines is the most efficient solution and could be further extended. For the lines that will remain non-electrified, battery electric, biofuels and hydrogen are the main alternatives18.

What are the implications for the energy transition?

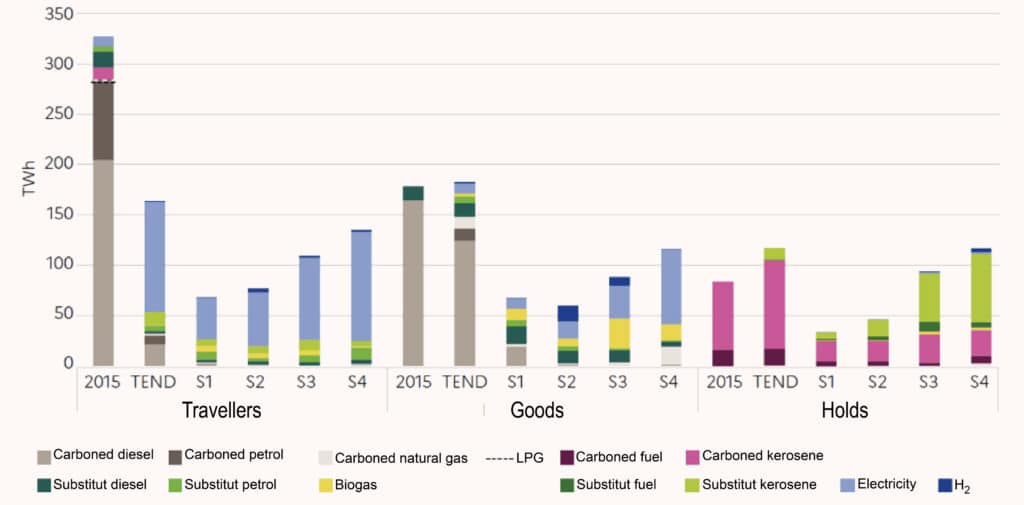

To move away from oil, freight transport will have to rely on a variety of energies in the future, while passenger transport will be largely dominated by electric power (as illustrated by the four ADEME Transition(s) 2050 scenarios below19).

Whatever the mode, decarbonisation is likely to be slow, costly, or face major technical and implementation challenges. The main decarbonisation options also depend on resources (metals, biomass, electricity, etc.) that are under pressure, whether within transport, with other sectors of the economy or because of the impacts linked to their exploitation conditions (impacts on biodiversity, geopolitics, social, etc.).

This should lead to prioritising the reduction of energy consumption in freight transport as much as possible, using the levers of sobriety (mentioned in the first article and detailed in the next two articles in the series). Both to decarbonise the sector quickly enough to meet the objectives, but also to limit the financial cost and other environmental impacts of the transition.