Six resources to prevent work-related mental illness

- Between 2007 and 2019, work-related psychological distress doubled in France, with a greater impact on women than on men.

- Since 2011, a map of psychosocial risks (PSRs), exposure to professional factors leading to a deterioration in psychological well-being, has served as a framework for professionals.

- To avoid these PSRs, six “Psychosocial Resources” defined by Yves Clot help to determine how to address them and the approach to take.

- These include, among other things, identifying paradoxical injunctions, recognising your own autonomy, and learning to be assertive.

- The latter corresponds to knowing how to defend your rights and needs without encroaching on those of others, which allows you to set boundaries while remaining constructive.

In France, work-related mental health issues are on the rise, with figures doubling between 2007 and 2019, according to Santé Publique France. Anxiety and depressive disorders top the list and, in the most serious cases, range from burnout to suicide1. There is also a marked gender inequality among these disorders: in 2019, 6% of women were affected, compared with 3% of men. This is a public health issue that is not sufficiently recognised as an occupational health problem.

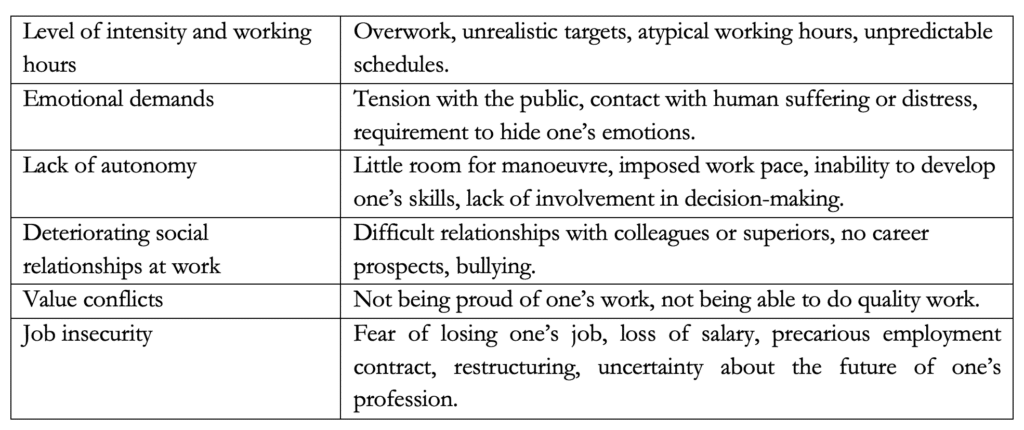

A psychosocial risk (PSR) is exposure to occupational factors which, through repetition and amplification, lead to “decompensation”, i.e. psychological deterioration in individuals. People who are exposed to poor working conditions over a long period of time may develop inappropriate coping behaviours, such as addiction to alcohol or drugs, or experience burnout. In 2011, a panel of experts commissioned by the French Ministry of Labour proposed a classification of PSRs, which is now considered reliable and serves as a framework for effective prevention2. This grid comprises six main categories, the content of which is regularly updated to take account of new risks (Table 1).

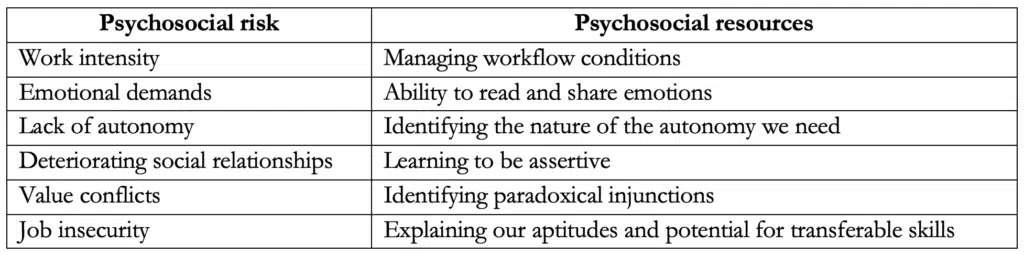

As such, methods exist to diagnose these risks within organisations3 and thus prevent them. These strategies consist of ensuring that people avoid experiencing these overwhelming situations. Beyond the problem and the risk itself, it is more important to focus on the approach to be taken and therefore the attitude to be adopted to address the issue. This attitude corresponds to a skill that can be developed by cultivating what Yves Clot, professor emeritus of occupational psychology at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, calls “Psychosocial Resources”4 (Table 2). These correspond to the conditions for a job to be done well and differentiate between being tired from meaningless work and the “healthy tiredness that comes from a job well done”. On this basis, we will review each of the risk factors and show which psychosocial resource enables a positive approach to work, when the context allows.

#1 The “flow”: don’t confuse intensity with overload

Have you ever found yourself absorbed in a demanding activity, so invested in it that you couldn’t think of anything else? Time no longer mattered, everything flowed smoothly, and your concentration was at its peak? This state of total concentration has a name: it is called “flow”. It is an optimal psychological state in which you are completely immersed in an activity, with a feeling of fluidity, intense concentration and pleasure in expressing your skills. In this case, the intensity of the work is entirely bearable, it is accompanied by motivation rather than stress, and it brings the satisfaction of a job well done.

Thanks to studies in occupational psychology, the factors that produce “flow” have been described:

- Having a challenge to take on while knowing that you have the individual or collective skills to meet it.

- Having clear objectives and rapid feedback, for example from your manager.

- Not being interrupted and having the means and flexibility to carry out the activity.

Work intensity is therefore not a psychosocial risk in itself as long as it is carried out under favourable conditions. But remove these conditions and add irritants such as frequent unexpected interruptions, unsociable hours, a lack of feedback and evaluation of the work done, unlimited versatility, a lack of recovery time, etc. the psychosocial risk becomes real and inevitable.

Many of us have experienced those moments when our body speaks to us and tells us to “stop”, even though we have had no warning signs. For some, it happens too late, and the body suddenly and violently gives way: the accumulation of these small additions ends up weighing more heavily than we had imagined. Rapid digitalisation is accelerating this downward spiral by adding small, harmless, inexpensive actions that are freely chosen but terribly engaging. The right questions to ask yourself in order to prioritise “flow” and avoid the pitfalls of intensity primarily concern the clarity of the working environment (realistic, clear and shared objectives; available resources; reasonable deadlines and schedules); managerial feedback (feedbacks) (including what we do well) and mental resources (in particular, room for manoeuvre and opportunities for recovery, just like an athlete: recovery is not an option!).

#2 Live your emotions or be lived by your emotions?

In many professions, direct contact with users or customers involves intense or difficult-to-manage emotions, such as aggression, anger, the distress of others, or even social deprivation. A simplistic and often-used solution is to try to strengthen employees’ resilience. To this end, several methods have emerged in recent years, such as relaxation and stress management workshops. However, these approaches tend to focus on employees rather than their environment. Psychological research has shown them to be ineffective5 and even harmful in some cases: for example, people who have undergone stress management training but are unable to regulate their stress effectively and therefore feel guilty. Or people who believe they can withstand more stress because they have become overly resilient.

It is clear that we all experience stressful situations at work: avoidance is not a realistic solution, nor is simply trying to become more resilient. Hiding your emotions will only cause them to resurface. The solutions lie in developing the ability to “read and share emotions”: knowing how to dissociate emotional reactions from the emotions themselves, learning to name one’s emotions, explain them and share them socially, with the aim of obtaining explicit support from one’s work environment6,7,8. In practical terms, this means setting aside short, regular periods of reflection or debriefing after critical situations to express emotions and difficulties. Being willing to discuss vulnerabilities, not with the aim of distancing oneself from emotions, but rather to integrate them as an integral part of the work situation and thus be able to consciously assess their risk. This emotional burden is also the source of a feeling of work overload: learning to identify it therefore has a double positive impact in terms of prevention.

#3 Encouraging autonomy to avoid despondency

We all need self-determination, i.e. the ability to make decisions, with some room for manoeuvre9. When we feel that we no longer have any autonomy, we develop what psychologists call a posture of resignation: we no longer bother, we no longer want to make an effort, to progress, to work with or for the collective, or to be creative. But taken to the extreme, autonomy itself becomes a constraint, a facade where the individual remains under implicit pressure to produce results, but without any real support.

Work is never reduced to the execution of rules or procedures: there are unforeseen events and necessary workarounds that will require adjustments to enable a job to be done “well”. It is therefore necessary to determine the rules within which autonomy will operate, and to do so we can rely on a diagnosis of the three forms of autonomy identified at work10:

- Autonomy in work planning: “how to do it”? To do this, clear objectives must be set (using the SMART methodology), but a margin of freedom must be left as to the means of achieving them, thus avoiding unnecessary “micromanagement”.

- Autonomy in organisation: “when to do it”? For example, the possibility of adjusting the timing oneself in response to unforeseen events.

- In decision-making: “what to do”? For example, the ability to test a new way of taking orders.

Regardless of position in the hierarchy, it is important to be able to explain the degree of autonomy that is needed: how much power an individual is given to influence their work” is given to each individual, based on their skills and also their interests? This is one of the keys to well-being at work. The same applies to responsibility, since the question of autonomy cannot be separated from the assumption of responsibility and therefore, ultimately, from risk. To reassure individuals, it is always advisable to define and clarify the levels of responsibility according to each person’s status and position. These elements help to clarify roles and reduce related tensions.

#4 Avoiding conflict in strained social relationships

Conflict prevention is often based on a truism heard in childhood: “it’s not nice to argue”11As a result, rather than anticipating conflict, we tend to avoid it. In business, this translates, for example, into “benevolent management”, which has become increasingly popular, particularly since the Covid-19 health crisis. Scientific journals12 draw our attention to two biases: on the one hand, the conceptual and methodological catch-all nature of benevolent management (which broadly consists of avoiding or even denying conflicts); on the other hand, very few studies seek to assess whether there are any negative effects of benevolent management. However, benevolence in social relationships and compassion in a professional context can have powerful paradoxical effects, such as excessive emotional dependence, the masking of real suffering, particularly in the context of deteriorated social relationships, or unrealistic performance pressures. To such an extent that some authors refer to the “positive toxicity” of benevolence13, the consequences of which are now well established: guilt, denial, manipulation, and the masking of deep-seated problems14.

It is important to cultivate an assertive attitude, which means knowing how to defend your rights and needs without infringing on those of others

This does not mean that we should not be benevolent! But how best to avoid avoidance? On the one hand, by being clear about the limits that must not be crossed, since they are prohibited by law, and on the other hand, by cultivating assertive skills. It is important for companies to explicitly reiterate certain obvious facts and their legal precedents: moral harassment is defined by the French Labour and Criminal Codes. Some companies have chosen to include codes of good practice in their internal regulations, which reiterate the rules in force, accompanied by procedures in the event of non-compliance, distributed internally and known to all. All of this is a bonus to accompany managerial discourse: mutual respect works better when the rules are reiterated! It should also be noted that in any company with more than 250 employees, a representative must be appointed to support the fight against sexual harassment and sexist behaviour.

In addition, it is important to cultivate an assertive attitude15,16, i.e. knowing how to defend one’s rights and needs without encroaching on those of others. In addition to knowing your rights, this involves developing skills in dialogue, speaking up and arguing your case, which allows you to set boundaries while remaining constructive. It is a fundamental psychosocial resource that allows you to anticipate deteriorating social relationships, favouring constructive confrontation rather than destructive confrontation or creeping passivity. Assertiveness prevents us from turning a blind eye to conflicts that we think will resolve themselves; it prevents the emergence of seemingly harmless sexist behaviours, which tacitly allow other, much more problematic behaviours to develop, which are then difficult to eliminate once they have become established.

#5 Conflicting values: false spontaneity?

“Be spontaneous”: this is a typical example of what is known as a paradoxical injunction, bringing together two opposing entities. Spontaneity cannot be commanded; you cannot do one thing without denying the other. The same applies when we tell someone to be creative in a highly restrictive environment, or to express their personality and be themselves, while remaining in control of their emotions in front of their team. Why are there so many paradoxical injunctions? Organisations are riddled with contradictory logic: they must combine quality and profitability, speed and rigour, autonomy and control, collaboration and competition. This is a reality. And there is nothing pathological about it in itself; it is normal. However, it becomes abnormal when there is no arbitration or regulation by the hierarchy, i.e. when individuals are left alone to deal with these demands.

These paradoxes give rise to what are known as value conflicts, which affect six out of ten workers in France17. These are situations where individuals must perform actions that go against their personal ethics, or activities that are completely meaningless, or where they are no longer able to do their job properly (known as “work impede”, which is even more true in traditional, craft-based professions that require precision). If these value conflicts are borne solely by individual employees, then they constitute real risks whose effects can have serious consequences, including legal ones.

Value conflicts are perhaps the most subtle and invisible aspect of psychosocial risks. But it is clear that they are not the least important. Sometimes what is left unsaid makes more noise than grand speeches. To prevent this risk, it is important to learn to identify paradoxical injunctions and even false dilemmas. To do this, spaces for discussion can be created to identify paradoxes, inconsistencies and contradictions, but also ethics and obstacles to work, for example during “free zone” meetings, where everyone can express what is contradictory in their work, thereby enabling management to take responsibility and make clear decisions on how to proceed.

#6 Job insecurity: what skills can be transferred?

Will you be demoted at work one day? Will you be replaced by AI? How will you keep up? Will you be able to continue doing your job until you are 67? It is legitimate to ask yourself these questions from time to time. But it becomes problematic if they take centre stage in our headspace. Job insecurity is the most difficult issue to grasp because, on the one hand, it is indeterminate (no one can predict the future) and, on the other hand, it is often perceived by managers as beyond their control, as it involves decisions that are not theirs to make: strategic, economic and political decisions. However, it is one of the aspects covered in mandatory career development interviews, as these discussions focus on future prospects, skills, training, aptitudes and, in other words, change.

This is why it is necessary, on the one hand, for these interviews to be conducted at a different time from performance reviews, so as not to dilute their importance, and, on the other hand, to standardise the interview guide so that managers can support and accompany their employees’ development plans. We need to consider the training and skills development available, internal job opportunities within the company, how employees’ current aptitudes can support the skills of tomorrow, etc. The challenge is to make implicit knowledge explicit18: talking about one’s work (in activity analysis, among peers) makes skills that would otherwise be invisible and therefore unsuspected visible and transferable.

Prevention of psychosocial risks

Acceptable periods of intensity, as they respect satisfactory working conditions; explicit support from management to support and accompany the emotions inherent in certain professions. A degree of agreed autonomy to increase the power to act; regular reminders of good practices in social relations to reinforce assertiveness; spaces for discussion to address and resolve conflicts of values; and clarification of everyone’s skills to secure career paths. Our analysis reinforces the idea that preventing psychosocial risks is not about strengthening individuals’ ability to withstand pressure, but rather about putting in place frameworks that respect and value each person’s psychosocial resources. This is by no means a utopian ideal; many companies already operate in this way, reconciling economic and human success.

Gollac, M. & Bodier, M. (2011). Mesurer les facteurs psychosociaux de risque au travail pour les maîtriser. Rapport du collège d’expertise sur le suivi des risques psychosociaux au travail. DARES, Ministère du travail et de l’emploi. https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_SRPST_definitif_rectifie_11_05_10.pdf↑

Mallick, M. (2024, 27 mai). Does your boss practice toxic positivity? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2024/05/does-your-boss-practice-toxic-positivity↑

Van Dijk, A. (2019). Substrats cognitifs et comportementaux de l’assertivité et de ses troubles. Thèse de doctorat de l’Université Paris VIII, disponible en ligne : https://www.theses.fr/2019PA080055.pdf↑

DARES Analyses, N°27,https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/publication/conflits-de-valeurs-au-travail-qui-est-concerne-et-quels-liens-avec-la-sante↑