Can we really measure the ecological footprint of the Olympics?

- The organisers of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games are promising to halve CO2 emissions compared with previous Summer Games.

- None of the recent editions of the Olympics have achieved the environmental targets initially promised.

- While a study of the London Games showed that the majority of environmental indicators were positive or negligible, the scientific community remains divided on the overall sustainability of the Games.

- The main source of greenhouse gas emissions from the Games is from visitor flights, followed by the construction of new buildings.

- To reconcile the Olympics and sustainability, several measures need to be considered, including staging the Games in the same cities and broadcasting them around the world.

The French capital is preparing to host the Olympic Games. With an athletes’ village, sports facilities and millions of visitors to welcome, it is hard to ignore the environmental impact of such an event. “The main source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the Olympic Games is from visitor flights, followed by the construction of new buildings,” explains Martin Müller. The organisers are promising to limit emissions: while the previous Summer Games emitted between 3 and 4 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e, a unit that includes all greenhouse gases), Paris 2024 is promising to halve this figure.

Holding this sort of an event will always have more of an impact than if it didn’t take place.

It must be said that this is not a new issue, and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) – the organising body of the modern Games – has also made it a priority. Sustainability is one of the pillars of the 2020 Olympic Agenda 2020, the IOC’s strategic roadmap, and the organising cities have a duty to demonstrate the sustainability of the event. “It is important to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but to say that the Games are sustainable makes no sense: holding this sort of an event will always have more of an impact than if it didn’t take place,” asserts Marie Delaplace.

What exactly are these impacts? A team from the University of East London carried out an impact study1 on the London 2012 Summer Games for the IOC. Of the 67 indicators considered, 15 concerned environmental impact. For ten of them, the Games had a positive impact: the creation of green spaces thanks to the redevelopment of a former industrial wasteland, improvements to the rail infrastructure (particularly in East London), new waste treatment facilities (particularly hazardous waste), an increase in the supply of accommodation and the sustainability of new buildings. As for the other seven, they are assessed as being negligible: water quality in the River Lee, air quality, land use, etc. And even GHG emissions thanks to emissions offsetting initiatives (which amounted to 3.3 million tonnes CO2e). No indicator has a negative impact. Overall, the authors gave the event an average sustainability rating (0.56 out of 1) for the environmental indicators, three years after the Games were held.

A question without scientific consensus

But the scientific community is divided on the issue of the sustainability of the Olympic Games. “In essence, they follow a principle of growth, which runs counter to the main principle of sustainability, namely the idea of living well while limiting the consumption of resources,” says Martin Müller. Nevertheless, the debate continues among scientists, as Martin Müller and his colleagues describe in the journal Nature sustainability2: for some, mega-events like the Olympics represent an opportunity to promote and present innovative solutions to global challenges, and are political levers towards sustainability.

How can we assess the real impact of an event like this? “The term “climate neutrality” is sometimes used, but this is a marketing term based on carbon accounting: offsetting emissions by buying carbon certificates,” explains Martin Müller. “Research has shown that many of these credits are unreliable and do not compensate for what they promise.” Although the IOC is asking cities to demonstrate their sustainability, scientists believe that the organisation is incapable of guaranteeing environmentally sustainable Olympic Games3: none of the recent editions of the Games has achieved the environmental objectives initially promised. Rio 2016, Beijing 2008, Vancouver 2010, London 2012 or Sochi 2014: the authors provide a long list of references to back up their findings. “The indicators considered by the IOC are far too general and global,” adds Marie Delaplace. “Rather than thinking in terms of impact, which implies a causal relationship, it is more relevant to talk about co-production. This reflects what happens during an event which, in fact, is anchored in time and space. This requires us to reason on a micro-territory scale.”

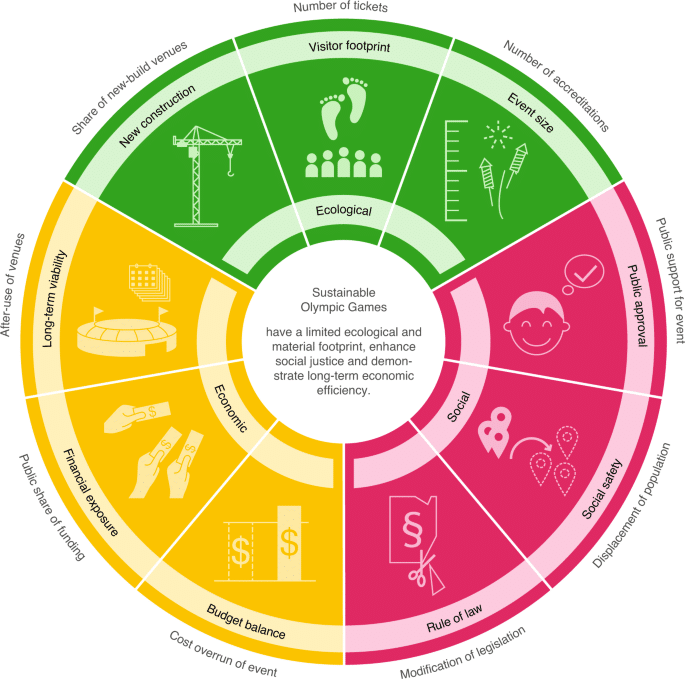

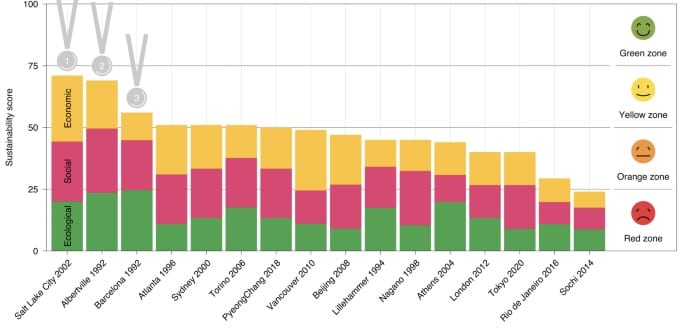

Looking at the 16 editions of the Olympic Games held between 1992 and 2020, Martin Müller and his colleagues assess the sustainability of the Games. Sustainability is defined by a limited ecological and material footprint, improved social justice and economic efficiency. Overall, sustainability is average (reaching a score of 48/100). Ecological indicators are even worse, scoring 44/100. Worse still, the authors show that sustainability – and particularly ecological aspects – has been declining since 1992. Sochi 2014 and Beijing 2008 received the worst scores for ecological aspects. Conversely, Albertville 1992, Barcelona 1992, Salt Lake City 2002 and Athens 2004 achieved the best ecological scores.

Post-Olympic Games: infrastructure legacy

On the other hand, the “long-term viability” indicator, based on the use of the facilities after the event, scores highly (76/100). It raises another important issue: what is the legacy of these events? The Paris 2024 organisers state, for example, that the Athletes’ Village, built on a former industrial wasteland, will be transformed into a sustainable district of the city4. “A similar transformation has taken place in London: there are a number of debates around the gentrification of the area versus social mix,” says Marie Delaplace. “The same controversies are now playing out regarding Seine-Saint-Denis.” Some of the facilities built for the Games (notably public transport) are of use to the local population afterwards, as was the case in London, but their usefulness is more disputed in Rio and Athens. “The question of the legacy of the Games is not easy to assess: the difficulty lies in having data that is sufficiently old to identify the true trajectory of the co-production of the legacy of the Games,” adds Marie Delaplace. “Some projects would have taken place without the Games, while others were implemented during the city’s previous bids. It is difficult to identify the actual starting point.” Martin Müller adds: “It is theoretically possible to take advantage of these events to accelerate low-carbon transitions, for example by introducing clean energy more quickly. But little research has been carried out, and previous studies have shown that the Olympic Games produce showcase effects, but fail to accelerate more important structural changes.”

Are there ways of reconciling climate change mitigation and the Olympic Games? The scientists suggest several approaches. Firstly, governance, to correct the IOC’s lack of effective incentives for sustainability. While the environmental impact of new construction is undeniable, some suggest that the Games should be held in rotation in the same cities. “An important step would be to bring the Olympic Games to the people, rather than bringing the people to the Olympic Games,” concludes Martin Müller. “The idea would be to have much smaller stadiums and for visitors to enjoy the Games in fan zones around the world, rather than travelling by plane”