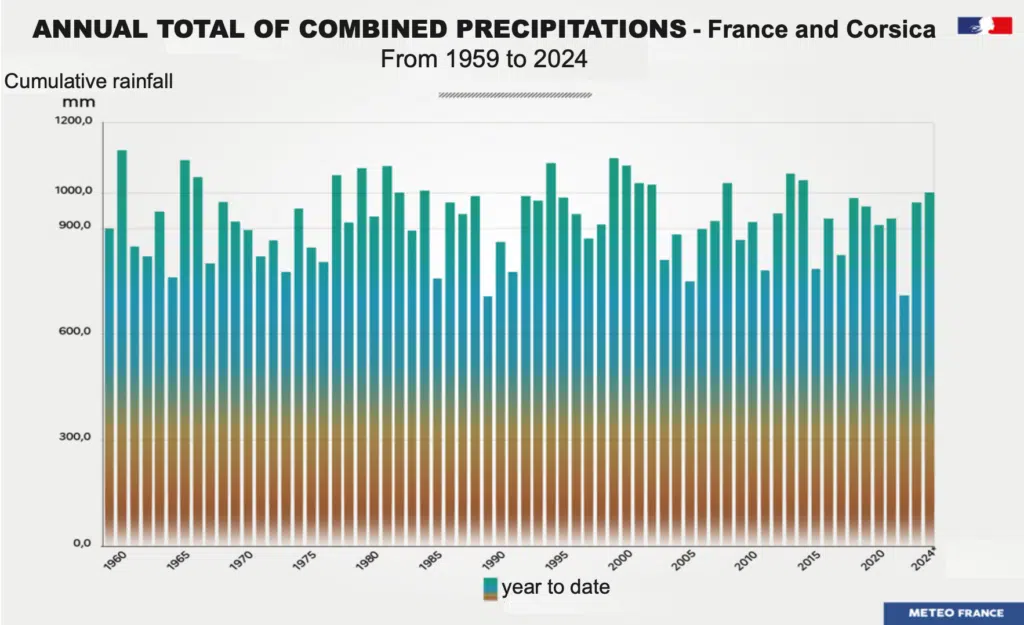

In France, 2024 was a year of heavy rainfall. The spring was the 4th wettest on record since 1959, and cumulative rainfall exceeded 1,000 mm nationwide since November, which is more than all the rain accumulated in 2023. “As early as the end of October, cumulative rainfall was in excess of the average annual total for the period 1991–2020,” comments Simon Mittelberger. “2024 was one of the wettest years since weather records began in 1959. On the other hand, the number of rainy days is in line with the average.”

Is there a link between this particular year and climate change caused by human activity? “2024 is mainly the result of natural climate variability,” says Simon Mittelberger. Weather conditions (precipitation, wind, temperature, etc.) are in fact modulated by natural oscillations in the climate as well as by the global rise in temperatures caused by human activities. The World Meteorological Organisation believes that it is necessary to consider a period of 30 years to observe climate change. “The shorter the time scales observed, the greater the impact of natural climate variability,” explains Bertrand Decharme. The annual scale is therefore far too short to reveal the impact of climate change on weather conditions. “A series of favourable weather conditions explains the high rainfall in 2024: numerous cold drops in spring, an atmospheric river in September and high temperatures in the Mediterranean,” points out Simon Mittelberger. It is therefore not possible to rely on the year 2024 to understand the impact of climate change on rainfall in France.

More rain in the north of France, less in the south

To do this, we need to look at the long-term trend in rainfall. If we look at the history of annual rainfall in France, there is no discernible trend. Cumulative annual rainfall in France has been around 935 mm since the 1980s, with natural variations from one year to the next. But when you change the scale, some signals emerge. For example, annual rainfall rose between 1961 and 2014 over a large northern half of France, while it fell in the south. “Since the 1960s, changes in rainfall patterns have also been observed between seasons,” explains Simon Mittelberger. “We’re seeing a marked increase in seasonal contrasts, with more rain in winter, particularly in the northern half of the country, and less rain in summer, particularly in the southern half.”

By releasing greenhouse gases, human activities increase the overall temperature of the atmosphere. Temperature has a direct influence on the amount of water in the atmosphere: this well-known physical relationship is known as the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. For each additional degree, the humidity of the air at low altitude increases by 7%1. As a result, global average precipitation increases, by around 1 to 3% for each additional degree.

In its latest synthesis report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sums up: “Global average precipitation and evaporation increase less rapidly than atmospheric humidity per 1°C of global warming, which lengthens the lifetime of water vapour in the atmosphere and leads to changes in precipitation intensity, duration and frequency, as well as an overall intensification, but not acceleration, of the global water cycle.” The regions affected in the future by an increase in mean annual precipitation are the Ethiopian Highlands, East, South and North Asia, south-east South America, northern Europe, north and east North America and the polar regions. Conversely, average rainfall will decline in southern Africa, the West African coast, the Amazon, south-western Australia, Central America, south-western South America and the Mediterranean.

France: a transition zone between northern and southern Europe

“France is in a transition zone: in the north of Europe, rainfall is set to increase as a result of climate change; conversely, the Mediterranean basin is set to become drier,” explains Éric Sauquet. “Is the transition between these two systems taking place in the north of France? Or in Belgium? It’s still difficult to get a clear answer from the climate models.” Climate change means an increase – which can already be seen today – in the contrast between seasons, but also between regions. “The high-resolution climate models we are working on establish the link between changes in precipitation in France and climate change,” points out Simon Mittelberger.

The Explore 2 project2, the results of which were published in the summer of 2024, is also exploring the possible future of climate and water in mainland France according to the IPCC’s climate scenarios, as Éric Sauquet, the project’s scientific co-leader, explained to us. “Between now and 2100, the projections don’t show any clear signals about annual rainfall,” points out Éric Sauquet. “On the other hand, rainfall in the future will show greater seasonal and regional disparities: the trends are clear for a decrease in summer rainfall, and an increase in winter rainfall under a scenario of high greenhouse gas emissions.” To put it plainly: the trends already observed today are set to continue.