Collagen: a key to preserving historical parchments

Whilst we may associate it more with aesthetics than antiquity, collagen is central in some cultural heritage objects. Indeed, this vital protein is a key structural molecule holding bodily tissues together to support cells. And since animal skin was used in centuries gone by to make parchments, the pages of many historical documents are full of collagen, too.

Collagen, collagen everywhere…

“There are around 26 different types of collagen, that are found in many organs – tendons, skin, cornea, arteries, lungs and so on,” says Marie-Claire Schanne-Klein a physicist at École polytechnique. She specialises in biophotonics, which essentially means that she uses techniques from physics to study living tissues. In her case, she works with advanced optical imaging, known as multi-photon microscopy.

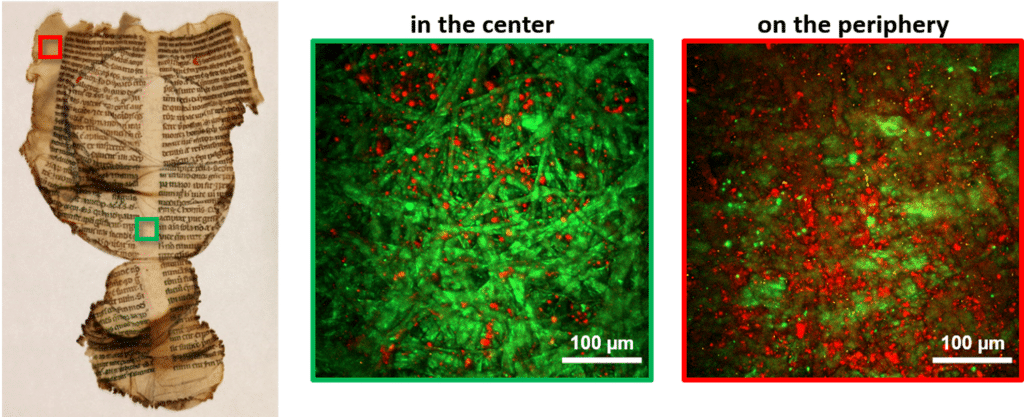

She explains, “we use fluorescent markers in biological samples to label different cellular components so we can see them under a microscope. But collagen doesn’t need a marker as it naturally generates harmonics detected in multi-photon microscopy which makes it glow without further intervention on our behalf.” Hence, this protein, which creates a ‘fibrillary matrix’ supporting cells, can be observed thanks to its harmonic signal. “These intrinsic imaging modalities, without any labelling are a speciality of our lab.”

“Collagen forms fibrils that are arranged differently depending on the tissue we are studying,” she clarifies. “In skin, for example, we would expect to see tangled bundles of large fibrils, which are responsible for its supple texture. Whereas in the cornea collagen fibrils are very thin and highly ordered, arranged in layers (or lamellae) that make it rigid, giving it the property of focusing light correctly onto the retina.” However, collagen may degrade, losing its fibrillar structure ultimately, forming a gelatine that no longer generates a harmonic signature, but still fluorescence.

Marie-Claire Schanne-Klein and her colleagues study the collagen principally for biomedical purposes. “Collagen structure plays an important role in many diseases. It can change in certain extreme situations like skin burns or scarring, which leave visible traces. But also, in certain cancers because tumours seem to form around structures of collagen as a scaffold. We tend to study them for that reason, to better understand the pathologies associated to collagen.”

Collagen in cultural heritage

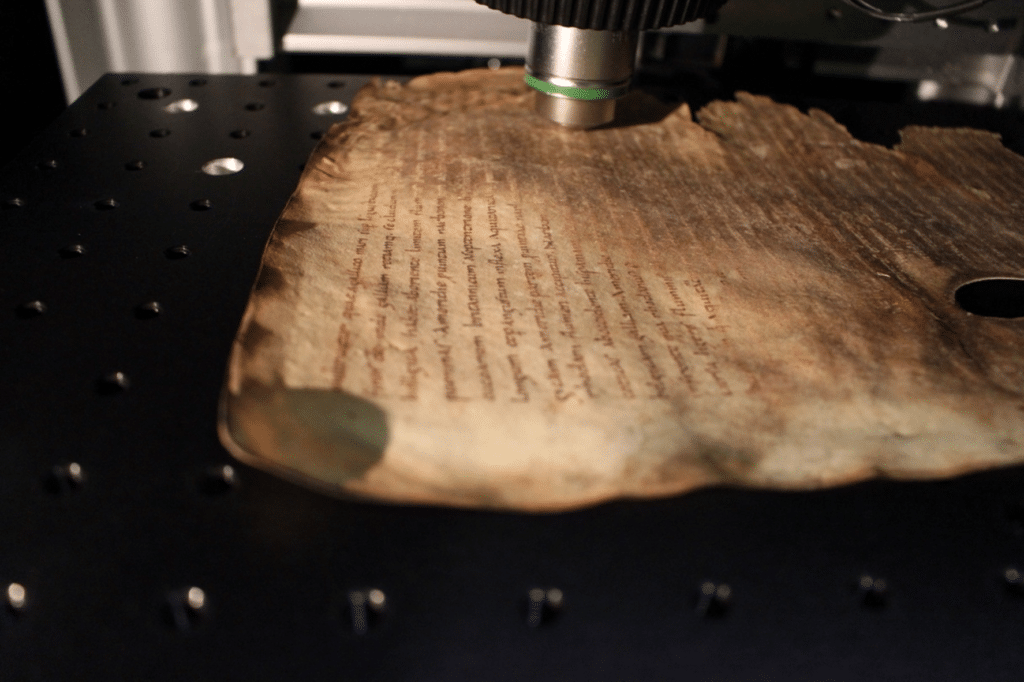

Interestingly, collagen is found in other places too, including many historical manuscripts written on parchments that are made from animal skin. Gaël Latour from Université Paris-Saclay studies these materials. “Parchments can degrade over time due to storage conditions, and as they do so they become increasingly transparent and rigid, leading to the loss of the readability of the writing,” he outlines. This transparent material is, in fact, degraded collagen, often referred to as gelatine.

“It is common knowledge in the world of cultural heritage that objects or documents made from skin will ‘gelatinise’ in this way. And now we know that this happens because the collagen fibres in the parchment unwind as it degrades, progressively transforming the material into gelatine. In doing so, the parchment gradually becomes more homogeneous, letting more light through.” Moreover, the process is irreversible: once the collagen-to-gelatine process has occurred the document is lost forever.

With his colleagues they have been studying documents used in Western Europe in the 13th Century, at a time before paper, when parchments were commonly used. But they have analysed documents that go as far back at the 8th Century. “Remarkably, some of the documents are still very well preserved, with just damage at the borders of the pages where they have been handled over the hundreds of years since they were made.”

Due to the collagen content of parchment, the team realised that they could use multi-photon microscopy to study it. “Currently, the main method for testing degradation of parchments is called differential scanning calorimetry; it’s a method that requires taking a sample from the page that is crushed into a pulp to be tested destroying a part – however small – of the document,” he explains. “But if we use multi-photon microscopy to study the collagen, we can do this in a non-invasive way.” In 20161, Latour, Schanne-Klein and colleagues, published a report showing that it was possible to see whether a parchment was degraded using their technique.

The researchers show that this method can be used to analyse the level of degradation – or ‘gelatinisation’ – of parchments.

Preserving history

“Initially the idea was to show that we could see degraded collagen in the parchments. So, in the beginning the idea was a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’,” he says. “But now, we are seeking to look at how we can quantify the amount of degradation. It could help us keep an eye on which documents need to be taken care of more effectively or help towards restoration efforts.”

Going further, they recently published another study2 in which they show that the technique can be used to analyse the amount of degradation – or gelatinisation – of parchments. They used these techniques to analyse custom documents, then historical ones preserved since the 13th Century from the archives of the Library of Chartres, France. In this particular case, over 200 of the documents had been exposed to heat from a fire during a bomb raid during World War II, resulting in extensive damage and gelatinisation. Gaël Latour and his colleagues used these invaluable pages to provide evidence that it is possible to quantify the amount degradation using multi-photon microscopy, whilst causing them no further harm.

“Now we want to also understand how the degradation happens,” Gaël Latour adds. We have been starting from modern parchments that we have artificially degraded. The team expose them to dry conditions and temperatures above 100°C as if they were ‘aging’ and then analyse them using microscopy to quantify the degradation. Marie-Claire Schanne-Klein adds, “normally, gelatine is formed from exposing collagenous animal tissue to high temperatures – that’s how gelatine used for candy is made, for example, and in the case of these documents. But we know that in most cases, the parchments haven’t been exposed to such heat. So, in other cases, it is likely the result of acidification due to bacterial activity on the documents, which can produce an acidic fluid due to humid conditions during storage.” The team are setting about studying how this happens in more detail and to challenge this hypothesis.

And they don’t plan on stopping at parchments. “There are many other historical objects that contain collagen, too.” Indeed, in museums skin can be found in range of materials including rawhide or leather that was used to make clothes or in natural history specimens. There are other biomolecules that exhibit harmonics, notably cellulosis in plants, so that we can analyse old fabrics and musical instruments made of wood and more generally a range of other objects – each with their own story to tell for years to come.

For further reading

- https://portail.polytechnique.edu/lob/fr/recherche/microscopies-avancees/multiphoton-characterization-cultural-heritage-artefacts

- https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03028091/document