Solutions for producing greener steel

- The steel industry is the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, accounting for 7% of global emissions.

- In response to the new Green Industry Act and the demand for steel and iron, the sector is seeking to decarbonise the manufacture of these metals.

- According to the IEA, the circular economy is an avenue in the short term, though sobriety should be encouraged as a priority.

- “Direct carbon avoidance” and “intelligent carbon use” technologies are already proving their worth, but still need to be developed.

- The EU and France are committed to a policy of relocalising industrial activity in order to minimise costs and environmental impact.

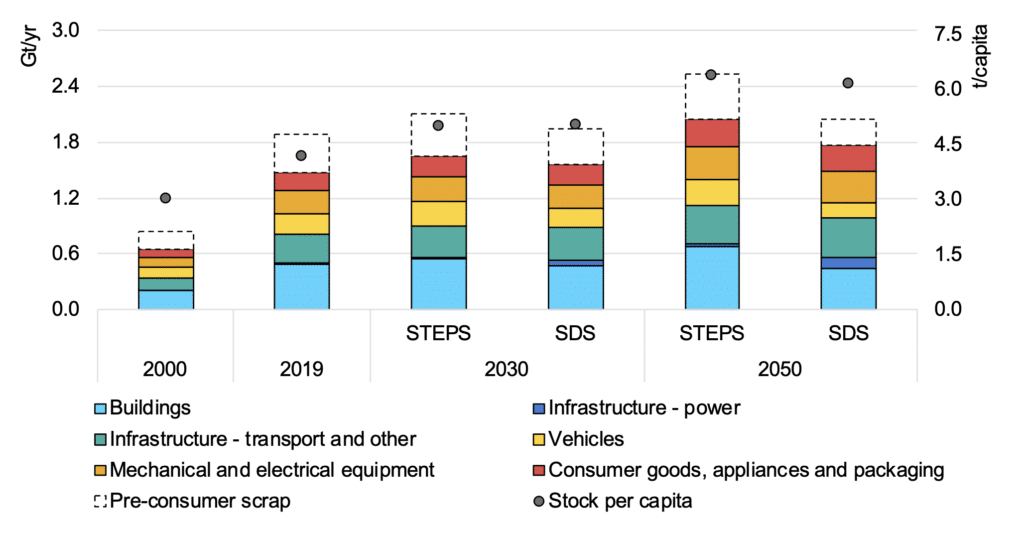

The Green Industry Act was passed on 11th October 2023. Its main aim is to decarbonise existing industries. The stakes are high: in France, industry accounted for 18.1% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 20221. The iron and steel industry is one of the biggest sectors to be decarbonised. In France, it is the 4th largest industrial sector in terms of GHG emissions (20% of industrial GHG emissions, or 4% of the country’s total emissions). But on a global scale, the sector is in first place: around 2.8 billion tonnes of CO2 are emitted every year in steel production, or 7% of global GHG emissions2. Yet demand is soaring. Steel and iron are essential for construction, mobility, and the production of renewable energy – a wind turbine is made up of more than two-thirds steel! According to projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA), global demand could increase by more than a third by 20503.

Source: IEA analysis informed in part by Pauliuk, Wang and Muller (2013), Cullen, Allwood and Bambach (2012) and Gibon et al. (2017)

How is steel made?

There are two main methods used around the world to produce steel, an alloy of iron and carbon. 70% comes from the cast iron process4: iron ore is introduced into a blast furnace in the presence of coke (produced from the pyrolysis of coal) and transformed into cast iron through chemical reduction. During this stage, the carbon combines with the oxygen contained in the ore to form CO2. The cast iron is then transformed into steel in a converter. Another process used is the electric arc furnace. This method is widely used to recycle scrap metal, which is melted in an electric arc furnace. There are several alternative methods: for example, ore can be used in the electric arc process. In this case, the iron is extracted from the ore by direct reduction using coal or natural gas, before being transformed into steel in the electric arc furnace.

Steelmaking requires large quantities of energy: for example, melting reaches 1,500°C in the blast furnace. Yet in 2019, three quarters of the energy consumed by the sector was supplied by coal. To date, recycling within the electricity sector is the most carbon-free option. It requires only one eighth of the energy of steel produced from ore, and mainly in the form of electricity rather than coal. “We need to increase the recycled proportion, but this sector is limited by resources: a large proportion of steel, for example, is immobilised for decades in buildings,” explains Fabrice Patisson.

Several effective short- and long-term solutions

In the short term, the circular economy is the most promising driver. Technological innovations for decarbonisation are based on renewing the production fleet, which has an average age of 13 years worldwide, or less than a third of its traditional lifespan. In its forward-looking scenario aiming for a 50% reduction in the sector’s emissions by 2050, the IEA points out that 40% of the cumulative reductions in GHG emissions between 2020 and 2050 are based on the circular economy. Simply put, this is the lever for energy sobriety: by reducing demand, emissions are reduced. This mainly involves extending the lifespan of buildings, but also improving manufacturing efficiency, reducing the use of cars and making them lighter, improving building design and reusing steel.

At the same time, a number of other solutions are available. It is impossible to meet rising demand without producing primary steel. One of the major levers for decarbonising production? Moving away from coal. The steel industry’s high GHG emissions are mainly due to the formation of CO2 in blast furnaces through chemical reactions, and the high temperatures required. “Green” iron would be produced by the direct reduction of iron ore using electricity or green hydrogen (H2), instead of coke. It can then be integrated into the usual electricity chain and transformed into steel in an electric arc furnace. This technology is known as “direct carbon avoidance”. “To date, the direct reduction process is well known and widespread – it accounts for around 7% of the world’s steel – but it relies on the use of syngas (a synthetic gas derived from natural gas), which contains around 60% H2,” explains Fabrice Patisson. “The biggest challenge is to go to 100% H2 on an industrial scale.”

The hydrogen route is the most advanced: of the 60 steel decarbonisation projects identified in Europe in November 2022, 42 are based on the use of hydrogen5. In Sweden, the Hybrit pilot project has been producing the world’s first tonnes of steel using this process since 2021. It could reduce CO2 emissions by 85%6. “From now on, the development of the sector depends on the willingness and capacity of steelmakers to invest,” says Fabrice Patisson. As for electricity requirements – if hydrogen is produced by electrolysis of water, they would amount to 370 TWh to decarbonise all the EU’s primary steel production7, or 14% of current total electricity production8.

There is another technological route – one that is complementary to the carbon avoidance route – and that is the “intelligent use of carbon”. This involves optimising existing production processes. Even if the industry has mastered blast furnaces, there is still room for improvement. It has been shown, for example, that more than half of the energy purchased by steelmakers is lost during the process9. Using the best available technologies and optimising processes could make it possible to reduce the sector’s cumulative global emissions by 21% between 2020 and 2050, according to the IEA’s forward-looking scenario, which aims to reduce the sector’s emissions by 50% by 20503. This involves deploying heat recovery systems, improving coke quality, partially replacing coal with natural gas or bioenergy, and implementing predictive maintenance tools.

Carbon capture and storage is an effective option in the short term, before clean technologies – such as hydrogen – are deployed

Intelligent use of carbon also involves its recovery. As in many industrial sectors, the capture and recovery or storage of CO2 is seen as essential if we are to make a success of the transition by 2050. According to the IEA, this could make it possible to capture 6% of the emissions generated between 2020 and 2050, with the capture rate rising to 25% per year by 2050. Only one commercial CO2 storage unit currently exists in the world, in the United Arab Emirates. A few recovery projects are currently under development. “CO2 capture is easier in the steel industry than in others,” adds Fabrice Patisson. “Capture and storage is an effective option in the short term, before clean technologies – such as hydrogen – are deployed.”

Finally, the EU and France are committed to a policy of relocating industrial activity. Gone are the emissions associated with transporting products. France’s energy mix, with its relatively low carbon footprint, is also an advantage in terms of GHG emissions. One of the avenues being explored is the development of clusters of activity based on an industrial ecology approach. “The aim of this approach is to design activity clusters, like ecoparks, that optimise the exchange of flows between different manufacturers,” explains Marianne Boix. “By pooling services, the supply chain, energy and raw materials, environmental impacts and costs are minimised.” GHG emissions can be cut by up to 75% compared with the same plant without cooperation10. The ArcelorMittal site in Dunkirk is a case in point: the slag – a by-product of the blast furnaces – is recycled as a building material, and the waste heat is fed into Dunkirk’s municipal heating network11. Two new EPR nuclear reactors are due to be built there, as well as a green hydrogen production unit… which will be able to supply ArcelorMittal’s future direct hydrogen ore reduction unit12. Marianne Boix concludes: “Integrating the hydrogen vector into ecoparks makes the process profitable, both economically and environmentally. It’s a very interesting opportunity in this context.”