The airship returns : what surprises are left in store ?

- Airships (i.e. blimps) could make a comeback, as they have undeniable advantages over other means of transport.

- However, because of their lightness, they are subject to hazards and bad weather: more precise means of prediction and control must therefore be developed.

- Computer simulation, the design of more resistant materials and wind prediction tools are making it possible to improve the new airships.

- They will not replace large-scale air transport but can be useful for tourism or inter-regional travel.

- Several companies, such as Flying Whales and Thales, are increasingly interested in the new airships.

Airships are often perceived as a technology from another era. When they came onto the market at the end of the 19th Century. This new means of transport was a worldwide revolution : in these enormous balloons, it was possible to cross the Atlantic in less than 60 hours and to travel at speeds of over 130 km/h.

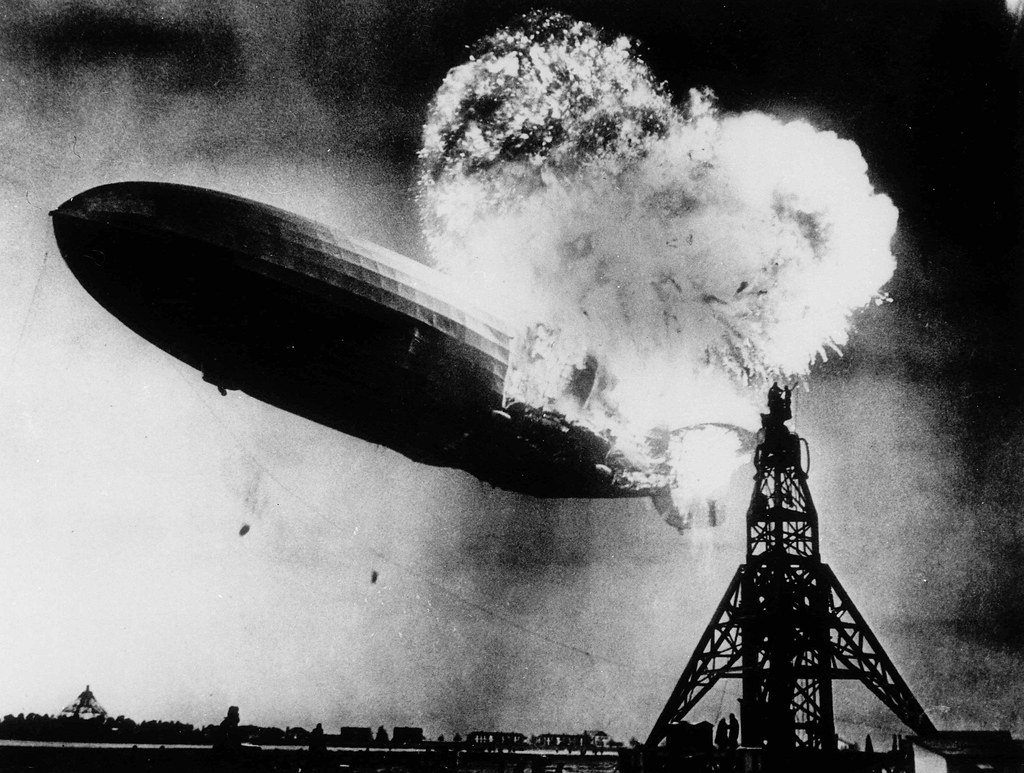

However, this technology did not come to a happy end. The Hindenburg disaster in 1937 – a colossus barely smaller than the Eiffel Tower that burst into flames in the skies over New Jersey – is still seen as traumatic even today. However, airships have undeniable advantages, and this accident has never called them into question.

Olivier Doaré, a professor of fluid mechanics, directed Robin Le Mestre’s thesis aimed at modelling the effects of external and internal fluids on the dynamic behaviour of airships in flight1. This research is therefore in line with a potential revival of airships, as Olivier Doaré maintains : “Since this disaster, there has been a century of technological progress.”

Dependence on the wind

The Hindenburg was inflated with hydrogen, a highly flammable gas. The Germans did not choose to use this gas by chance : helium, which is much less flammable, was already recommended at the time, but was much harder to find. The lack of supply was due to the geopolitical context of the period. The United States, which had a virtual monopoly of the helium market, wanted to keep its lead in this technology.

“Nowadays, the vast majority of airship projects are inflated with helium for safety reasons,” explains Olivier Doaré, “even though, for the same lift force, this requires a greater volume of gas than with hydrogen”. However, the idea of a hydrogen-fuelled airship has not been completely abandoned : “In the case of electric propulsion provided by a fuel cell, hydrogen could be the carrier gas and the fuel at the same time,” suggests Robin Le Mestre.

These two gases are used because they are lighter than air. “The airship is self-supporting thanks to Archimedes’ thrust (in other words, buoyancy),” explains Robin Le Mestre, “so it requires almost no energy to keep it in flight. This is a considerable advantage, especially in the current ecological context, but it does imply constraints that must be taken into account. “Because of its lightness, the machine will be highly exposed to the vagaries of the weather,” admits Robin Le Mestre.

To mark the return of airships, it will therefore be necessary to master these already identified meteorological constraints. “This is the whole point of my thesis,” says the PhD. “To go against the action of the wind, we need much more precise means of prediction and control.”

The potential of this thesis has also attracted the attention of the French aerospace research centre, ONERA. Jean-Sébastien Schotté, a research officer at ONERA, helped develop these prediction tools. According to him, “better modelling of the couplings between the airship’s deformable structure and the flow of the surrounding gases will make it possible to improve simulations of the airship’s in-flight behaviour, for example in the face of gusts of wind, and this could help in the design and sizing of future airship projects.”

Better prediction

In addition to these advances in the field of digital simulation, other progress has been made in the design of materials : “The materials used today are more resistant, more watertight, while being lighter,” says Jean-Sébastien Schotté. “Moreover, wind prediction tools exist and are very effective,” says Olivier Doaré. LiDAR technology, for example, these wind prediction lasers, which are currently useful for optimising the control of wind farms, could also be useful for airships. “However, to predict the actual trajectory of an airship, and thus ensure its safety, a multitude of environmental factors must be taken into account,” says the professor. “So much so that it is difficult, with today’s resources, to perfectly simulate the behaviour of the craft on a computer.”

In fluid mechanics, the Navier-Stokes equations are fundamental. They allow us to represent the most complex movements of fluids – and therefore many of these environmental factors – but they are far too cumbersome to be used in complete simulations of the in-flight behaviour of large flexible structures such as airships. “The first step was therefore to simplify the Navier-Stokes equations to retain only the essential elements,” explains Robin Le Mestre. “By postulating hypotheses on each interaction to be studied, we were able to formulate simplified, but nevertheless realistic, equations in order to be able to model the system and its operation through a set of mathematical operators, which can be digitised.”

Airships are self-supporting thanks to their buoyancy so require almost no energy to stay in flight.

With this simplification, the researchers were able to offer a realistic simulation that could be accessed by rapid calculations. In the long term, the engineers hope to be able to adapt the controls of the aircraft to real-life situations. “A plane has so much power, because of its weight and its engines, that if the pilot wants to go left, he takes the controls and, whatever the wind and his behaviour, he will go left,” says Olivier Doaré. An airship will be greatly affected by the wind, and its engines may not be sufficient. There is a greater interest in combining our knowledge of the effects of the wind with that of the craft’s controls.

The research work in progress, of which Robin Le Mestre’s thesis is a part, therefore aims to help manufacturers optimise the design of airships, for example by enabling them to develop tools for predicting controls in real time based on wind data.

A specific use

Size, impressive as it is, remains a drawback to the potential use of airships. Blimp models are inflated balloons with a minimum of structure. The advantage of this type of model lies not in the safety aspect, but in its payload. However, in comparison with an aeroplane, for the same number of passengers or goods, the volume required will be much greater. “From a personal point of view,” admits Olivier Doaré, “I don’t think that the airship of tomorrow will replace the plane. Firstly because of the weight of the aeronautical industry, but also because of the disadvantage of the size of the structures.”

Indeed, an airport requires a fairly large space to accommodate aircraft. For a fleet of airships, the space required would be “insane”. Passenger transport will only be possible on a small scale and could be beneficial in a few situations : “From a touristic point of view, the airship can offer services similar to a hot-air balloon ride,” says Robin Le Mestre. As far as transport is concerned, there is a growing interest in inter-regional travel, or to areas without airports, such as many islands.

Aerostats : the large family of airships

Airships are machines that belong to the family of aerostats. This family includes hot-air balloons and tethered balloons. Both of these devices use technology similar to that of airships, and the results of this thesis can also be applied to them.

Tethered balloons, for example, are used for observation missions. They allow surveillance of areas for military, ecological, topographical, or simply fisheries control purposes. They are also useful for communications purposes. What is more, once deflated, their lightness allows for rapid transport and deployment in sensitive areas.

Controlling the behaviour of the craft in bad weather, while being able to predict it, would give them the advantage of great stability in the air. This characteristic, combined with the low amount of energy needed to keep them in the air, makes them very useful, even in the face of their competitors, the drones.

“The technology is not intended to replace large-scale passenger air transport, but its many advantages make it useful in many other areas. Airships can still carry several dozen tonnes,” he says. They will be useful for specific sectors, especially those where time is of little importance.

The company Flying Whales, for example, is interested in this thesis. “The company wants to develop a prototype airship in a few years’ time, for transporting loads in inaccessible areas, such as forests in mountainous regions,” adds Robin Le Mestre. Transporting wood to an inaccessible forest by truck in this type of craft will be more efficient than by helicopter, for which the storage space is smaller and the journey more expensive.

The company Thales, in partnership with ONERA, has also launched the “Stratobus” project2, an airship designed to fly in the stratosphere. This airship will fulfil missions that are complementary to those of satellites, in a surveillance, communication and defence function. It should be noted that many projects are currently flourishing in industry : airships are therefore not yet finished !