Diving into the minds of musicians to uncover new learning strategies

When studying the brain, neurobiologists tend to focus on the structure and physiological functions of our body’s most vital organ. Homing in on the different cells (namely, neurones and glia) scientists study the ways in which they interact through neural networks and chemical messages in the form of neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, adrenaline etc.). And how, biologically, the multifarious components of this cerebral orchestra harmonise as one. However, they do less often study the thoughts generated by these biochemical and physiological elements.

As such, biologist Prof. Pierre Legrain (Institut Pasteur) is taking a rather unconventional approach to study the human mind to uncover how the brain learns new things. Contrary to standard practise, he uses a holistic phenomenological experiment that consists of simultaneously collecting experimental data on perception and individual reports from test subjects through introspective interviews. He asks the question: what does a person experience when his/her brain performs specific functions?

Learning to learn

“There are children for whom teaching methods we use today do not work,” he announces. “I mean, there are a lot of kids who have learning difficulties, and we tend to think that these kids aren’t ‘good’ at school. Yet, there is a lot of evidence to suggest that it is the way we teach these children that needs to be adapted – it’s not their fault.”

He is referring to learning skills that, he says, most of us take for granted. Previous work suggests that many children who are struggling in the educational system do so because they have not mastered the mental strategies necessary to succeed in school. As a result, many of those who struggle to learn the basics of reading, math, or even social skills, may simply be lacking cognitive abilities that can, in fact, be learnt.

“For example, when you hear or see things in your mind and relate those ideas to the real world, you are improving your cognitive abilities. This process is implicit and seems obvious to many of us, but it is not obvious for everyone,” he says. Legrain works closely with his colleague Alain Letailleur, a specialised teacher for pupils with severe learning difficulties, who has examined these theories on those children. In doing so, he had previously helped children learn to better use their brains by picking up cognitive strategies such as mental visual, auditory or kinaesthetic associations, such as combining a mathematical operation with the gesture made on the calculator.

Legrain and Letailleur therefore seek to better understand what learning strategies are possible in order to offer them to children with learning difficulties.

Musicians under the microscope

To study what happens to the brain as it learns – in terms of thoughts, not in a directly biological sense – they are using musicians as test subjects. Under controlled conditions, they played them a musical note, which they then had to identify as quickly as possible. “In general, they respond almost immediately,” he points out. It’s an important factor because the test relies on the logic that the subjects all hear exactly the same thing and identify it as the same note. Therefore, the input and output of the brain are as constant as it can get.

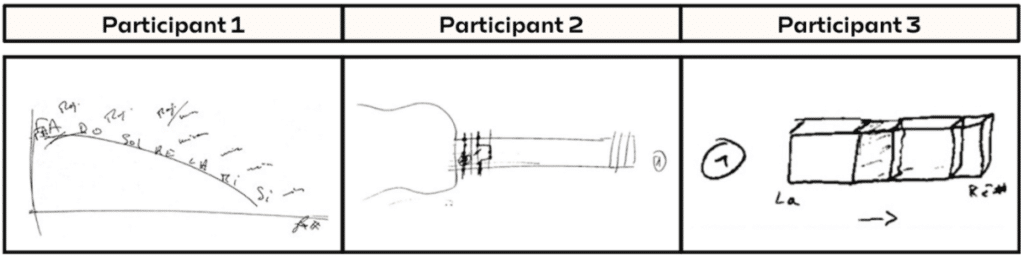

The only thing that changes, therefore, is the thought that occurs in the musician’s mind. He continues, “after the response, we asked them to describe what they felt when their brain identified the note.” They did this in different ways, sometimes using a drawing to formalise the idea. Interestingly, the musicians described a variety of experiences – many of which were very different from one another. Amongst them were descriptions of vibrations, images, association with emotions, their musical instruments, bodily responses or more, allowing the team to create a collection of different mental strategies used by their test subjects.

Nonetheless, the key finding came from comparing the two distinct groups in the sample of musicians they studied. He explains, “on the one hand, we had music students and on the other, professional musicians. The mental mechanisms described by the students tended to be related to learning strategies, whereas the professionals used thoughts more related to their artistic practice, such as the instrument they play.” Hence, with a musician’s ‘expertise’ or proficiency in their craft, the subjects seemed to have developed their own personalised mental strategy for identifying musical notes. “We named these mental anchorpoints [appuis mentaux, in French].”

From the music hall to the classroom

The next step will be quite complicated because it means taking several musicians who use different mental anchorpoints and studying them together. “We are now examining the different strategies used in the hopes of objectively classifying them. We will then need to find a way to specifically interfere with one or another mental anchorpoint to specifically prevent a musician from recognising the note.”

This approach is novel in that it attempts to link biological findings to the psyche, which has rarely been studied until now, so the challenge is there. To bridge this gap, the team will combine their findings with neuroimaging to identify the neural circuits that are involved. “We would like to be able to better characterise these mental anchorpoints in order to find effective ways to apply them to academic learning.”