IQ: can intelligence really be measured?

- IQ is not an objective measure of intelligence. In fact, it is a relative measurement which has its own errors, measures only certain facets of intelligence and is subject to uncertainties.

- An IQ below 70 is not synonymous with mental disability but should always be accompanied by other tests or examinations to provide a more in-depth analysis.

- An IQ test is a clinical tool used, for example, to assess the cerebral consequences of a cranial trauma or to detect a deterioration in cognitive faculties due to ageing.

- The measurement of IQ cannot be separated from education, social and family background or culture of origin, because intelligence is linked to these factors.

- The average Western IQ has risen sharply since the 1940s and stabilised since the 21st Century, perhaps approaching a form of human limit.

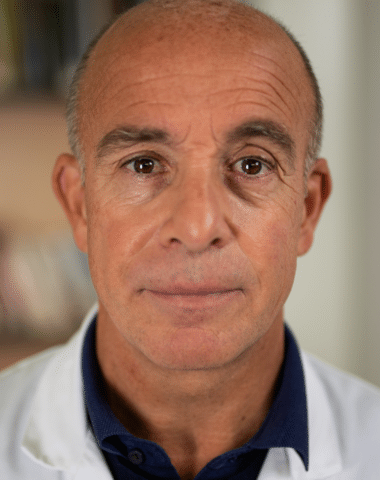

The purpose of the intelligence quotient (IQ) is to estimate a person’s intelligence, using a tool made up of a series of questions: the IQ test. Taken in conjunction with a psychologist, the test produces a score which can be compared with the average for the population in question, set at 100. But to what extent can IQ tests be used to assess intelligence? Jacques Grégoire, Emeritus Professor of Psychology and Psychometrics at the Catholic University of Louvain, looks at some of the main misconceptions surrounding IQ.

IQ is an absolute measure of intelligence – FALSE

The intelligence quotient (IQ) is sometimes considered to be an objective measure of intelligence, but this is not the case. Intelligence is a quality that cannot be seen, so how can it be measured? From the beginning of the 20th Century onwards, researchers refined their knowledge of the structure of intelligence. This has led to the development of major sets of tests to assess various facets: verbal, visual-spatial, working memory, etc. Current tests estimate an individual’s intellectual level based on the results obtained in the various exercises.

But it should be noted that this is only an estimate. Firstly, the score is a relative measure: it defines where the individual stands in relation to the average for the group to which they belong, which is set at 100. What’s more, any measure – in psychology, as in any other field – is subject to error. This is why IQ should always be given with a confidence interval, for example of plus or minus five points.

What’s more, an IQ test is subject to many uncertainties: the conditions under which the test was conducted, the objective sought, the deliberate or inadvertent errors made, etc. As a result, it is imperative that the result obtained be accompanied by an analysis by a trained practitioner. Without interpretation, an IQ score means nothing.

A low IQ indicates a mental handicap – INCONCLUSIVE

IQ is constructed in such a way that, within an interval of plus or minus one standard deviation around the mean (from 85 to 115), we find 68% of the population. Consequently, having a score below 100 is certainly not a sign of intellectual disability.

There is, however, a standard whereby a score of two standard deviations below the mean (less than 70) is considered to be a sign of mental disability. But this score alone is not enough to make a diagnosis. It must always be accompanied by other tests or examinations, to provide a more detailed analysis.

Especially as the result of an IQ test can be influenced by many factors. For example, fatigue, drug use or a psychiatric condition can affect an individual’s performance. This means that IQ tests are not always reliable.

Everyone needs to know what their IQ is – FALSE

An IQ test is first and foremost a clinical tool, used to meet a specific objective: to diagnose mental disability, to assess the cerebral consequences of a cranial trauma, to detect a deterioration in cognitive faculties due to ageing, and so on. The question must therefore be of a general nature: what is the problem to be solved? The IQ test may – or may not – help to achieve this goal, but it is not an end in itself. Some people want to consult a professional to find out their IQ, often in the hope of obtaining an exceptionally high score. But what’s the point? Even in a professional or educational environment, IQ is not enough to predict performance. Other indicators may be more relevant, such as results in examinations, competitions or technical tests. The IQ test should not be used as an absolute reference to classify individuals; that is not its purpose.

IQ test results show differences between men and women – TRUE

Just over forty years ago, IQ tests showed gender differences: girls performed less well on visuo-spatial functions (ability to visualise in 3D an object represented in 2D) and better on verbal tasks. Today, these disparities have completely disappeared. This means that there is no scientific data to support a gender-specific orientation. On the other hand, there is one area in which girls generally obtain better results than boys: perceptive speed, which reflects the ability to spot small differences. This was true over forty years ago, and it remains true today.

The French have a higher average IQ than Americans – INCONCLUSIVE

The purpose of an IQ test is always to compare an individual with the group to which they belong, for example their compatriots. On the other hand, it makes no sense to compare two different populations: there is currently no tool that can do this. In the past, some initiatives aimed to develop culture-independent tests whose results would not depend on the country. But this is impossible because intelligence cannot develop outside of culture.

This close link is sometimes confirmed in unexpected ways. Take the following task: having to remember a sequence of numbers and reconstruct it in reverse order. The perfect example of an exercise free from any cultural influence, isn’t it? Well, a previous study showed that one country performed significantly worse than other Western countries: Lithuania. And why was this? In the Lithuanian language, most words for numbers have two or three syllables. And working memory storage depends on the length of the words to be remembered, which is greater here than in other languages. So, there are many examples of questions that may seem universal, but which in reality hide major disparities between countries. This is why any relevant test needs to be adapted to each culture, which requires a significant amount of work.

IQ depends on social and family environment – TRUE

Intelligence, while partly innate, can only develop in a favourable context. School, family and social environment all play a fundamental role. As a result, IQ cannot be measured without reference to education or the social and family context, because intelligence is linked to these. This may seem unfair, but it is a reality that can be seen in other areas: the child of two top sportsmen and women will more easily develop athletic skills, and the same is true of the children of professional musicians.

The average IQ in France has fallen in recent years – FALSE

Thanks to complex statistical models, it is possible to make comparisons between eras. And from the 1940s onwards, there has been a fairly clear increase in average scores in Western countries over the decades. This is known as the Flynn effect. But this trend largely slowed down in several developed countries as the 2000s approached, to the point of stagnation; not regression as some studies with methodological weaknesses claim.

How can this phenomenon be explained? There is no absolute certainty, but it is reasonable to assume that the growth in IQ was encouraged by the improvement in living conditions after the Second World War: lower mortality rates and childhood illnesses, more schooling, higher living standards, etc. And in recent years, we may be approaching a kind of limit in terms of average intelligence. Don’t human beings have limits in every field?

For example, at the 1896 Olympic Games, the winner of the 100 m race took 12 seconds. Since then, this mark has been progressively improved, dropping below 10 s. But will a human being ever manage to run the 100 m in under 7 or 5 s? There’s bound to be a limit that cannot be exceeded.