How did the James Webb Space Telescope discover its first exoplanet?

- In June 2025, the James Webb Space Telescope discovered its first exoplanet, TWA 7 b, the lightest extrasolar planet ever observed by direct imaging.

- Today, thanks to coronography, we have direct images of a few dozen exoplanets out of the 6,000 identified to date.

- Until 2025, coronography had only allowed us to see super-Jupiters, planets with a mass greater than that of Jupiter.

- The discovery of TWA 7 b confirms theories about the structure of debris discs and provides insight into the formation and variety of planetary systems.

- The next generation of instruments is in the pipeline: the Extremely Large Telescope is expected to come into service around 2030, and the Habitable Worlds Observatory around 2040.

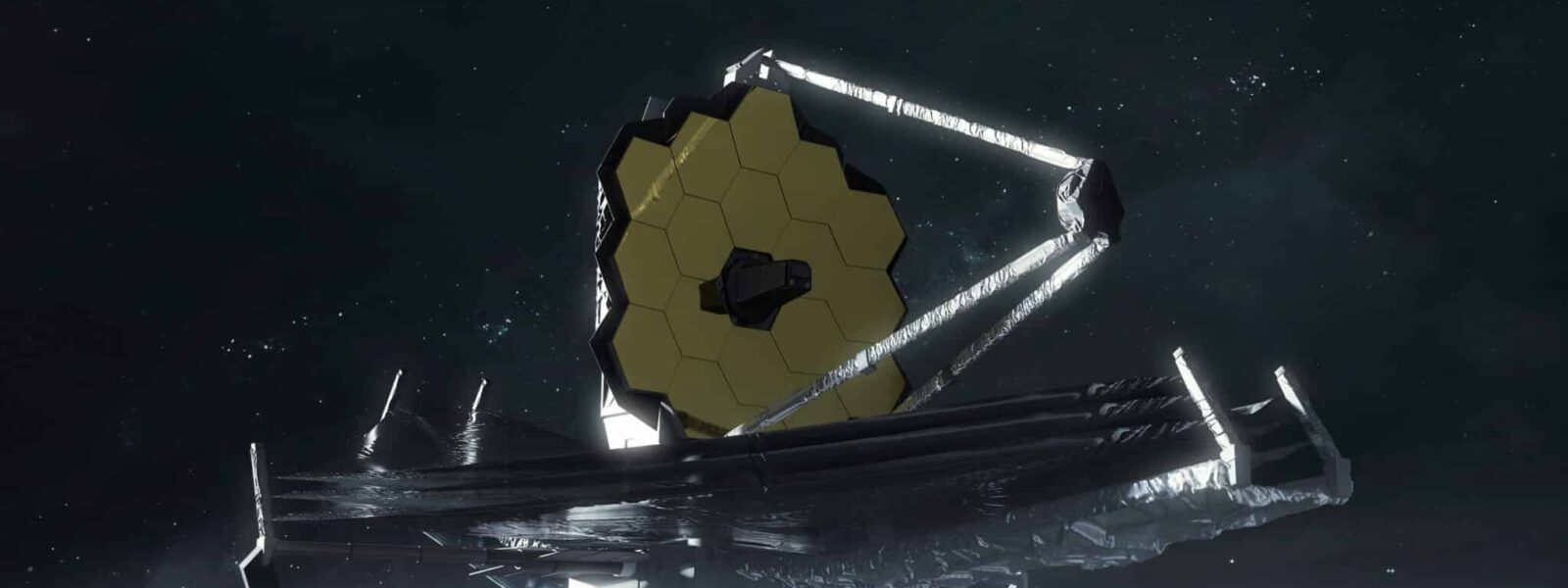

It’s a first and a record: in June 2025, Anne-Marie Lagrange’s team at the Paris Observatory announced that the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) had just discovered its first exoplanet, TWA 7 b. The size of Saturn, the newcomer becomes the lightest extrasolar planet ever observed by direct imaging. This discovery illustrates the telescope’s exceptional performance and marks an important milestone in the search for new worlds.

To understand what new perspectives this result opens up, let’s go back to the mid-1980s, ten years before the discovery of the first exoplanet. At that time, debris disks—crowns of dust and particles surrounding certain stars—fascinated some astrophysicists. “We were only beginning to be able to see them. The first image of such a system, the disk surrounding Beta Pictoris, dates from 1984,” recalls Anne-Marie Lagrange. “Rapidly, others were observed—about a hundred are catalogued to date—revealing a fascinating diversity of structures.”

At the turn of the 21st century, researchers postulated that certain “anomalies” could, in theory, be due to the presence of planets

At the turn of the 2000s, researchers postulated that certain “anomalies,” such as the fine gaps carved into certain disks, could theoretically be due to the presence of planets. But these planets, millions or even billions of times less bright than their stars, remained invisible. To try to work around this difficulty, researchers decided to apply to the search for distant planets an old technique that appeared in the 1930s for observing the surroundings of our sun: coronagraphy. It consists of creating an artificial eclipse of the star—in the past through occultation, today through destructive interference. Thus, we now have direct images for a few dozen exoplanets—out of the approximately 6,000 identified to date. But this method has its limits, and until 2025, it had only allowed us to see super-Jupiters [Editor’s note: planets with a mass greater than Jupiter’s], much more massive and brighter than the objects supposed to create the fine gaps in debris disks.

A change of scale with JWST

Hence, we had to wait for the JWST—and its record-breaking instruments—to hope to go further. Because one of the telescope’s innovations lies in the coronagraphs integrated into the MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). Optimised to enhance the contrast between the star and the planet in the mid-infrared, and therefore much more sensitive than their predecessors, they were notably developed by teams from CNRS and CEA. “There is a remarkable expertise pipeline in optical instrumentation in France. The first coronagraph was invented in 1931 by a Frenchman, Bernard Lyot. It was also a Frenchman, Pierre Léna, who played a central role in the development of adaptive optics, now used in all terrestrial telescopes. These remarkable skills are explained notably by the presence in France of an excellent engineering school in this field, the Institut d’Optique, created in 1917,” explains Anne-Marie Lagrange.

Choosing the right star

But it was still necessary to find a candidate worthy of the telescope’s performance. TWA 7, a small star located 111 light-years from Earth, was thus carefully selected from among the hundreds of thousands of stars accessible to JWST. Not only did its debris disk, highly visible, unambiguously present the sought-after gaps, but these gaps were far enough from the star for the telescope to distinguish a planet hidden inside, without being blinded by the star’s light. Even better: TWA 7 is no more than 6.5 million years old, and this great youth guaranteed that its potential planets, still hot, would emit massively in the infrared, JWST’s domain of choice.

Mission accomplished: at 50 astronomical units from TWA 7, inside a narrow gap carved into the debris disk, MIRI captured TWA 7 b, ten times lighter than the least massive exoplanet directly observed until then. “It was located exactly where our simulations predicted,” emphasises Anne-Marie Lagrange.

Better understanding planet formation

Beyond the technical feat, what does the discovery of TWA 7 b teach us? “First of all, it confirms our theories about the structuring of debris disks, and opens the way to many more advanced models, to better account for the formation and evolution of these disks,” comments the researcher.

“But this observation also represents an important contribution to understanding the formation and variety of planetary systems.” Indeed, the richer a planet is in gas, the more its formation is supposed to occur rapidly after the birth of its star, because the hydrogen and helium not used to form the star escape very quickly into interstellar space. “TWA 7 b proves that a very young system can already harbour a sub-Jovian mass planet, and this is precious information for refining our models.”

“Finally, the discovery of the exoplanet also provides an opportunity to study, perhaps even with JWST, the primitive atmosphere of a Saturn-like planet.” And this is valuable, because it proves very difficult to “go back” in time from observations alone of the solar system’s planets, which are more than 4.5 billion years old.

What’s next?

Will JWST go further? Will it flush out even lighter exoplanets? Will it be capable, above all, of seeing Earth analogues—those terrestrial planets located in the habitable zone of their star, on which researchers hope to find traces of life? “We would still need to gain a factor of 10 to 30 on the planet’s mass,” reminds Anne-Marie Lagrange. “JWST won’t be able to make that leap.”

But the future generation of instruments is already in preparation: the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), with a diameter of 39 meters (nearly 4 times wider than the largest currently in service), under construction by Europe in Chile should enter service by 2030. Similarly, the American space telescope Habitable Worlds Observatory, equipped with coronagraphs even more sensitive than James Webb, could be launched around 2040. It will fall to them to take the step toward these habitable worlds.