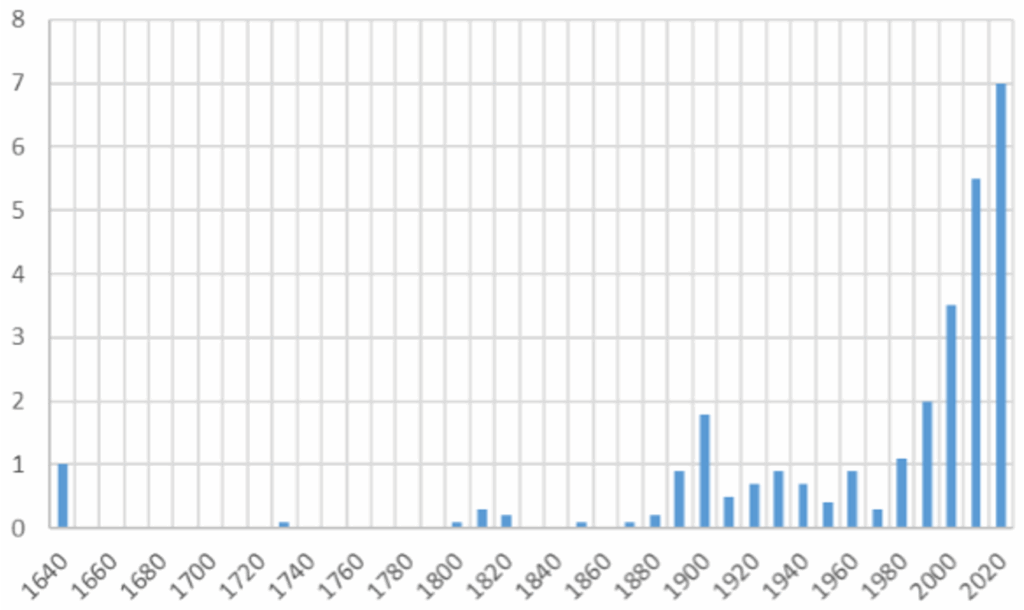

At the end of May 2025, the village of Blatten in Switzerland was largely destroyed by a glacier collapse, claiming the life of one victim. In mountainous areas, a triggering event – such as heavy rainfall or high temperatures – can destabilise sloping terrain1. This sometimes leads to cascading processes, resulting in rockfalls or glacier collapses, for example. These risks have always existed, but anthropogenic global warming is altering their frequency, magnitude and location2. Why is this happening? Rising temperatures are causing glaciers and permafrost to melt, reducing the stability of slopes. In France, the number of glacial and periglacial events accelerated at the end of the Little Ice Age (late 19th century) and again since 1980 (fig. 1.). In regions with small glaciers, such as the Alps and Pyrenees, many glaciers will disappear well before the end of the century, regardless of the mitigation efforts implemented.

Monitoring glacier melt is crucial. Natural hazards, freshwater resources, sea level rise, tourism… their melt has an impact on many aspects of society. However, until recently, data remained very sparse on a global scale. “Before satellites, we didn’t know how many glaciers there were in the world,” says Fabien Maussion. The first global inventory of glaciers dates back only to 20123. While only a few hundred glaciers are monitored on the ground, satellite measurements provide mapping and monitoring of changes in nearly 220,000 existing glaciers4. “It was a revolution, a new field of research was created: large-scale glaciology, continues Fabien Maussion.

Satellite data: a revolution in glacier observation

The first satellite glaciology data was extracted from images taken by the ASTER sensor on board the Terra satellite, which has been in orbit since 19995. “The mission was not intended for glaciology, but American scientists quickly realised its potential for this field of research,” says Étienne Berthier. Glaciers were then very quickly included in the acquisitions.” In practice, scientists rely on stereoscopy: based on two slightly offset satellite images of the same region, it is possible to reconstruct the region in 3D. This model is called a digital terrain model [DTM]. By comparing the difference in altitude of glaciers over time, it is then possible to estimate their melting6. “With the ASTER and TanDEM‑X satellite missions, the scientific community has access to optical and radar space missions that enable it to assess changes in the altitude of glaciers around the world over the last two decades,” write the authors of an article in the journal The Cryosphere.

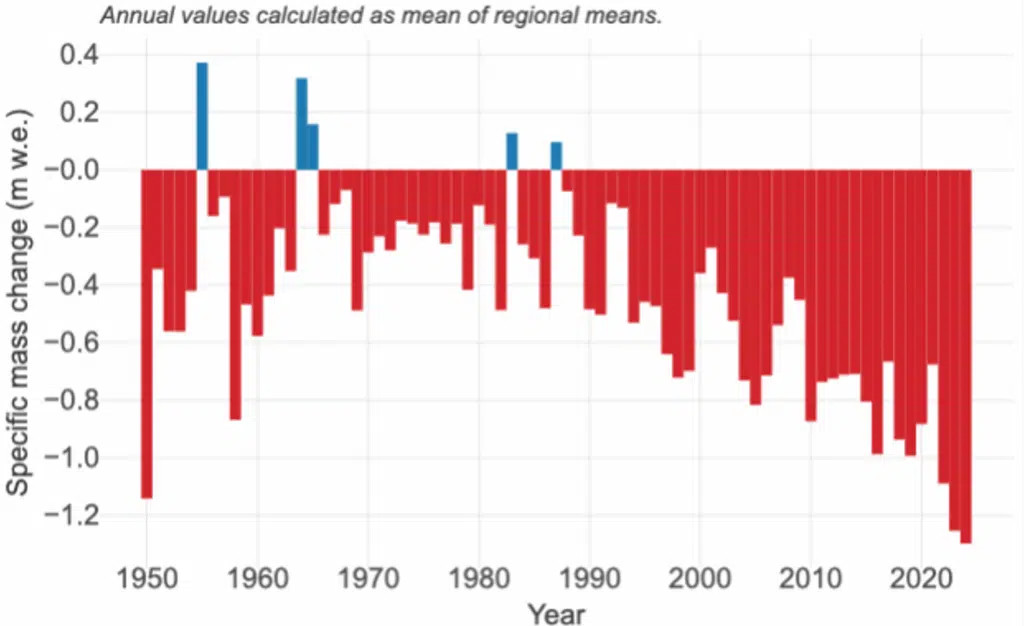

As a result, knowledge about glaciers is increasing exponentially, and they are becoming key indicators of climate change. Changes in mass (fig. 2.), surface flow velocity, extent and snow cover of the world’s glaciers are being scrutinised in detail by satellites, which are carrying more and more instruments – interferometers, radars, lasers and gravimeters7. In 2021, the first estimate of the volume variations of all glaciers was published: between 2000 and 2019, glaciers lost 267 billion tonnes per year, representing one-fifth of the global sea level rise8. These recently updated data show a 36% acceleration between the first and second decades of the period studied9. “We have also highlighted that glacier retreat is not uniform across the planet,” adds Étienne Berthier. Supplementing this with older data from field measurements, another study shows that since 1976, glaciers have lost more than 9 trillion tonnes10. This represents a global sea level rise of more than 2 cm due solely to the melting of mountain glaciers.

Between inevitable glacier melt and the importance of mitigation measures

“We use this vital information about the past to calibrate our mathematical models,” emphasises Fabien Maussion. “This enables us to calculate projections of future changes in glacier mass and their contribution to sea level rise. This information is used by the IPCC and decision-makers and is only possible thanks to satellites.” Last May, an international team (including Fabien Maussion) showed that the loss of certain glaciers, such as those in the Alps, is inevitable at current levels of warming [11]11. But scientists also highlight the importance of climate change mitigation: twice as much glacier mass would be lost if warming reaches 2.7°C by the end of the century (the current trajectory) instead of 1.5°C.

Satellite data has revealed the global extent of glacier melt over the past two decades. “However, there are no satellite missions dedicated to glaciers, and some current missions will end within the next two to three years,” observes Étienne Berthier. “To ensure the continuity of high-resolution spatio-temporal observations, we are promoting the 4D Earth mission to space agencies.” As climate change is a long process, data covering several decades is needed to quantify its consequences. While such data exists for some glaciers thanks to older field measurements, it is rare in certain regions of Asia and South America2. Finally, it is impossible to do without field data from satellites. “Field measurements enable us to produce seasonal assessments and measure the density and thickness of glaciers. For example, it is essential to know the density of the snow covering glaciers and how it changes over time to calculate mass changes from satellite data,” concludes Étienne Berthier.