The James Webb Space Telescope has arrived safely at its destination – the famous Lagrange point L2 located in the interplanetary void of our Solar system, some 1.5 million kilometres from Earth. But why there ? What is so special about Lagrange points, of which there are several, that space agencies have been sending satellites to for the past 50 years ?

The three-body problem

Since Isaac Newton formulated the laws of mechanics and gravitation at the end of the 17th Century, the “three-body problem”, which consists of determining the motion of three celestial objects under their mutual gravitational attractions, has been one of the most fruitful problems of classical physics. Attempts to solve it have led to countless theoretical advances, which in turn have enabled many revolutionary practical applications. Even though we have a much better understanding of the problem and its difficulty, in particular thanks to the work of Henri Poincaré at the end of the 19th Century, it is not, to this day, completely solved.

Lagrange points naturally appear as special solutions of the so-called ‘restricted’ three-body problem, in which one of the bodies is very small compared to the other two. This is the case for the motion of a satellite around the Sun and a planet.

The balance of forces

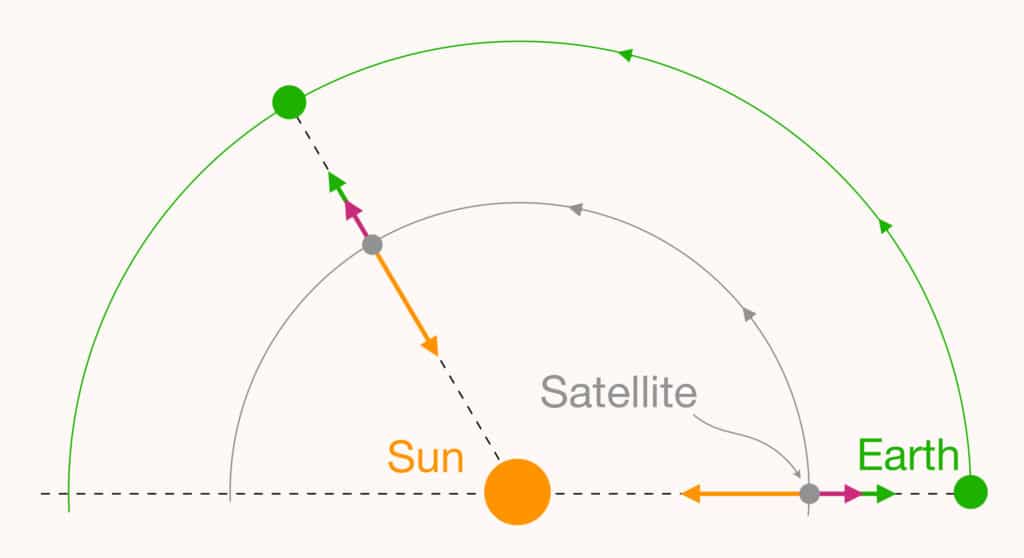

Let us first consider the orbit of the Earth around the Sun, which is a near-perfect circle. The Earth makes a complete orbit around the Sun in one year, a period known as its revolution. Let us now imagine placing a satellite in a circular orbit around the Sun with the the same revolution (exactly one year) and such that it always lies on the Earth-Sun axis. By adjusting its distance from the Sun in just the right way, the force of attraction of the Sun will exactly compensate for that of the Earth and the satellite will be ‘in equilibrium’.

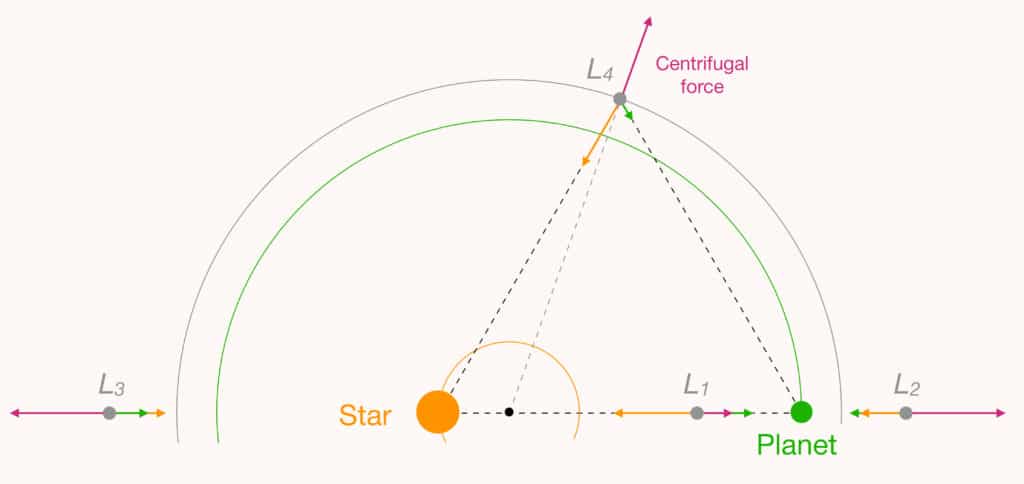

However, the satellite is also subject to a centrifugal force (the one that pulls us outwards in a merry-go-round). This force adds to the gravitational attractions, but does not change the big picture : we can always adjust the position of the satellite on the Sun-Earth axis so that the three forces cancel one another, as shown in the figure below.

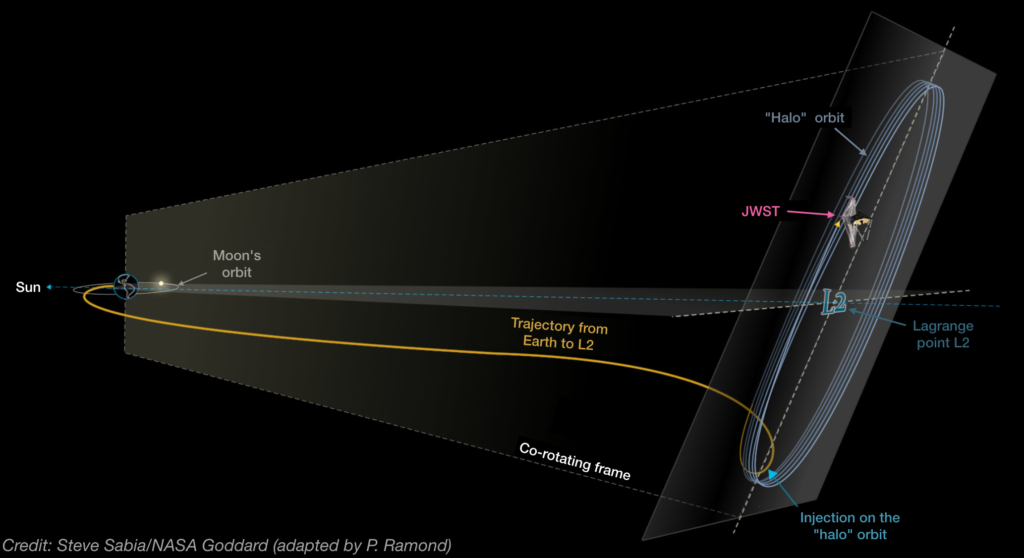

The co-turning reference frame

The orbit that we have just constructed for the satellite is precisely what astronomers call a ‘Lagrange point’. But why Lagrange ‘point’ and not ‘orbit’? The reason lies in another way of looking at our problem. Indeed, since the satellite and the Earth orbit the Sun in a year, we can imagine orbiting with them, and take this revolution into account in the graphic representation of the problem. The satellite’s trajectory is then reduced to a point, placed between the Sun and the Earth, which is also fixed in this so-called ‘co-turning’ reference frame. This point, which in fact represents an orbit, is the Lagrange point L1.

The first three

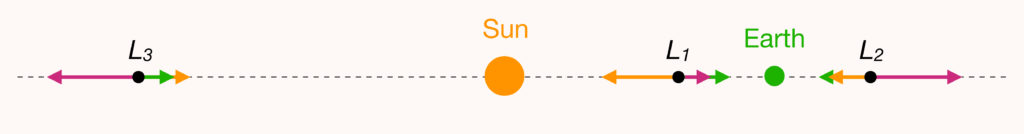

The co-turning reference frame is very useful and allows us to uncover four additional Lagrange points, by simply looking for other spots where all three forces (Earth and Sun’s attraction and the centrifugal force) cancel out. Two of these points, called L2 and L3, are also on the Sun-Earth axis, as shown in the figure below.

The Lagrange point L2 lies on the other side of the Earth from L1, and L3 on the other side of the Sun. It is clear from the figure that the three forces experienced by a satellite at these points cancel out : this is why they are also called ‘equilibrium points’. Together with L1, the points L2 and L3 correspond to three exact solutions of the three-body problem determined by Leonard Euler and published in 1765. Located at the opposite end of the Sun from us, the point L3 has been the subject of many flights-of-fancy since ancient times. One of these is a hypothetical ‘anti-Earth’, which would exist at L3 but which would be exactly hidden from us by the Sun.

Artificial satellites

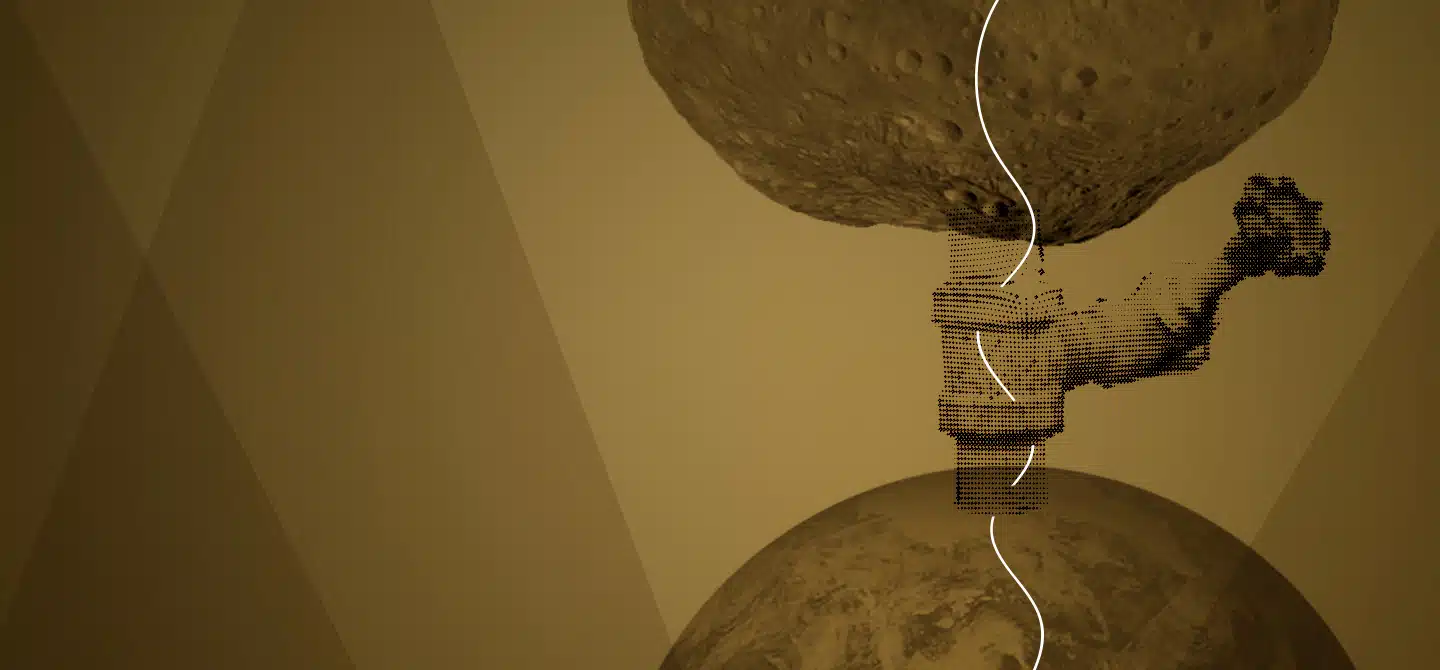

On the practical side of things, it is mainly the L1 and L2 Lagrange points that have interested space agencies. Indeed, satellites are regularly sent there for specific scientific missions. The first time was in 1978 with the ISEE (International Sun-Earth Explorer) programme, whose modules were placed in orbit around the L1 Lagrange point of the Sun-Earth system (located at 1.5 million km, that is, at less than 1% of the Earth-Sun distance). Since 2018, the L1 point in the Earth-Moon system (326,000 km from Earth, 15% of the Earth-Moon distance) has also been home to the Chinese relay satellite Queqiao, which communicates with the Chang’e 4 lunar probe on the far side of the Moon.

The point L2 (also located about 1.5 million km from the Earth) of the Sun-Earth system is home to some of the most extraordinary space missions. Among the most recent is the Planck satellite1, launched in 2009 to measure the oldest light in the Universe (known as the cosmic microwave background) with extreme precision. Another is the LISA Pathfinder satellite, which was launched in 2015 and which aimed to demonstrate how mature the technology needed for the future LISA space gravity interferometer is. More recently, the Gaia mission2, which catalogues the position, speed and light of more than a billion celestial objects (stars, but also asteroids, galaxies, etc.), has also found itself at L2. The latest satellite to reach L2 is the James Webb Space Telescope3, launched on 25 December 2021. Successor to the famous Hubble Space Telescope, its mission is to study nearby exoplanets and explore the farthest reaches of the Universe to observe the very first galaxies.

It may sound crowded up there and you might ask yourself : don’t all those satellites at the L2 point run the risk of colliding with each other ? After all, there is only so much space at a Lagrange ‘point’! Fortunately, these satellites are not sent to the exact position of the Lagrange points, but in orbit around them, in an area that is huge compared to the scale of a satellite : several hundred thousand kilometres in diameter. The satellites are thus in orbit around the Lagrange point, but the small number of adjustments required to keep them there are negligible compared to what it would take to keep them in such an orbit elsewhere in the Solar system. This is the main advantage of Lagrange points : gravitation and mechanics ‘naturally’ take care of a satellite’s motion so that astronomers can devote themselves to the beautiful science that these missions allow !

The last two

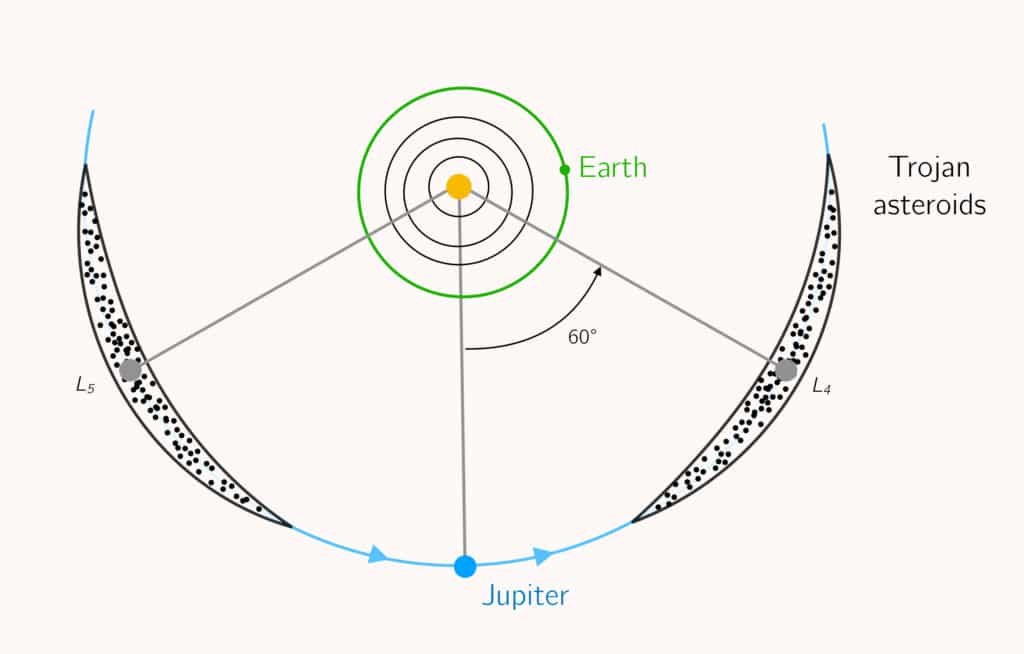

It was Joseph-Louis Lagrange who showed in 1772 that two other points, L4 and L5, exist. These are not on the Sun-Earth axis, but located at equal distance from both, so as to make an equilateral triangle. At these points, the two gravitational forces and the centrifugal force, although not aligned, still cancel out exactly, as shown in the figure below. In practice, the satellite is therefore almost on the Earth’s orbit, 60° ahead of (L4) or behind (L5) it.

Natural objects

Since Lagrange points are associated with equilibrium positions, it would not be surprising to find natural objects (such as small asteroids) at these locations in the Solar system. In the case of the Sun-Jupiter system, about 10 000 asteroids have been observed to date around the L4 and L5 Lagrange points. Called Trojan asteroids, some of these even have natural satellites of their own, such as the largest called ‘(624) Hector’ and its asteroidal moon “Scamandrios”.

These thousands of objects are proof that the Lagrangian stability regions are real and not just theoretical. In fact, most planets of the Solar system have Trojan asteroids, that is, small rocky bodies located near the L4 and L5 locations of the corresponding Sun-planet system. However, one mystery remains, as no Trojans have ever been observed for the Earth-Saturn system. It is suspected that gravitational disturbances created by Jupiter prevent asteroids from staying there too long4. Yet, ironically, two of Saturn’s natural satellites, Tethys and Dionne, have Trojans themselves !