Plastic waste : the need to act quickly before we are submerged

[This article is a summary of a note published by the Institut des politiques publiques. To read the original article click here]

In January 2021, the European Commission banned the export of difficult-to-recycle waste to non-OECD countries. We have examined the potential impact of this new measure for French exporters by comparing it to China’s abrupt decision to ban plastic waste imports in 2017.

Plastic as a raw material

An estimated 6.3 billion tons of plastic waste were produced worldwide between 1950 and 20151. Only about 20% of this waste was recycled or incinerated. The rest has accumulated in landfills or in the environment in general2.

Plastic waste is now a traded commodity sold by the tonne. In theory, developing countries (with low labour costs) should be able to profit economically by importing this waste. In practice, however, most do not have the infrastructures to treat the waste correctly. It therefore just ends up on rubbish heaps.

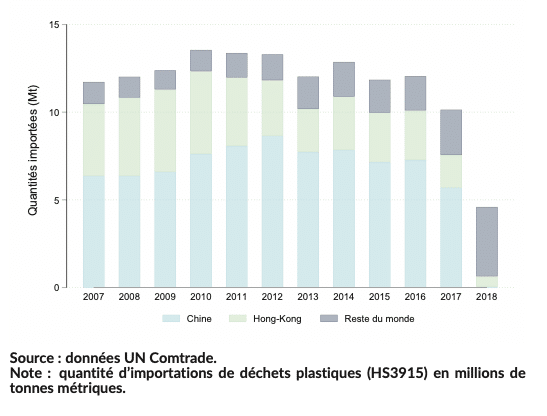

Despite the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal, which was signed in 1989 to protect these countries from “environmental dumping”, exports of hazardous waste have remained high. To counter this phenomenon, some emerging countries have adopted unilateral measures. The most radical of these was the 2017 ban by China, who no longer wanted to be the “world’s rubbish-bin” (figure 1).

China’s decision not only changed the status quo of global plastic waste management, it also dramatically revealed many of its shortcomings on a national level. So much so that the European Commission, for its part, adopted new regulations from 1 January 2021, both for within the EU and between the EU and the rest of the world. Except for clean waste sent for recycling, the export of plastic waste from the EU to non-OECD countries (that is, less industrialised nations) is now prohibited. Exports to OECD countries and within the EU are also more strictly regulated.

China’s ban as a comparison

France exported 4 million metric tonnes (Mt) of plastic waste between 2010 and 2019. About a quarter of this waste was shipped mostly to China and the rest sent mainly to other EU countries. To better predict the impact of the new regulatory changes introduced by the European Commission, we analysed how French exporters had previously adapted to the Chinese ban – in terms of quantities exported, destinations and prices.

We used a data set provided by French customs. This information does not, however, take into account illegal trade, which is difficult to estimate. We compared how the behaviour of two groups of companies changed following the 2017 decision. The first, or “treated”, group included firms that were actively exporting to China in 2016 or 2017. The second, or “control”, group was not exporting to these destinations.

What does the study show ?

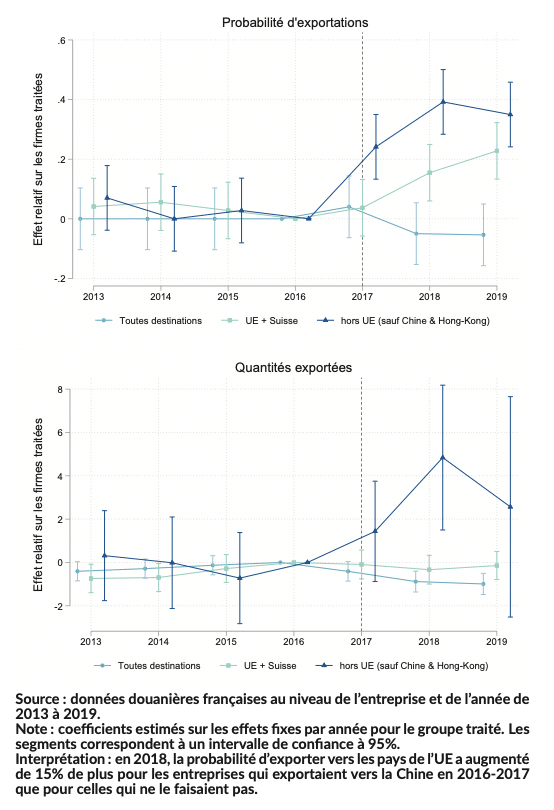

A collapse in global trade in plastic waste, which fell by a half by 2018. It also highlights that half of the waste previously exported to China has been reallocated to other countries (figure 2). The problem has thus largely been displaced.

France, for its part, increased exports to Malaysia and other East Asian countries, but not to the EU, implying that this latter market was already saturated. Overall, exports fell by 30,000 tonnes in 2018, suggesting that more plastic waste had to be processed domestically. Treated French companies were also 15% more likely to export to the EU in 2018 and 22% more likely in 2019. The figures are higher for exports to outside the EU with an additional increase of 39% in 2018 and 37% in 2019.

We did find, however, that the situation was very different for the two sets of destinations : affected companies reacted immediately by redirecting their exports to other countries outside the EU, but they also started to redirect these exports to European partner countries from 2018 onwards – and increasingly so in 2019. A longer time period would be needed to confirm these trends.

The quality of French exports and prices

The Chinese ban also affected the type of plastic waste exported by France to other countries. The data shows that Malaysia has replaced China for when it comes to low quality waste, which is sold on average 60% cheaper than the average price of exports to the Netherlands (an important trading partner for France) for the same product categories.

What is more, the different European member states seem to have reorganised their plastic waste management and a form of specialisation has appeared. Belgium has become a platform, for example, while Germany and the Netherlands import the cheapest waste and burn it to produce energy from recycled materials. Certain countries, such as Italy and Spain, are focusing on processing higher quality, more expensive waste.

Conclusions

The way in which the 2017 Chinese ban affected French exports both within the European market and to the rest of the world can provide valuable information on how France will adapt to the new 2021 EU regulations. One important consequence is that much of the country’s difficult-to-recycle waste will now have to be treated at home. In the short term, this will require massive investment in modern and efficient sorting and recycling infrastructures. Any delay in setting up these systems could encourage an increase in illegal trade in this lucrative sector. This is something that happens in general when policies are tightened and state investment is lacking.

Our study provides guidelines for quick action by making use of initiatives such as the Green Pact for Europe, which aims to recycle 50% of the plastic waste generated by the EU by 2030. Concerted efforts by member states could allow the trade in plastic waste to become a source of economic gain for Europe by 2030, while being beneficial for the environment.