Why are semi-conductors so crucial?

Mathieu Duchâtel. They are essential to the functioning of both the automotive industry, which is currently undergoing a major transformation, and the IT industry. The latter is absorbing high-end, high value-added processors and memory chips for production of smartphones, computers, and data centres. It is also worth noting that semiconductors are essential to the defence sector from missiles to the field of cybersecurity – now a major factor in military operations – making their design and production strategic.

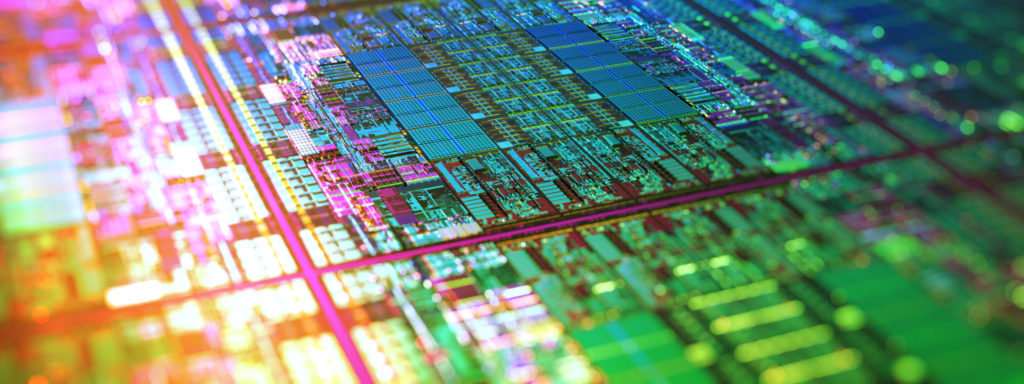

The market of semi-conductors is estimated at $600bn; with the major design and production centres found in the USA, China, Europe, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. Principally, design companies are American (Broadcom, Qualcomm, Nvidia, Apple) and production companies Asian (TSMC, Samsung, SMIC). A distinction is made between the most advanced technologies (with nodes equal to or less than 7nm; today 5nm, tomorrow 3nm and then 2nm), which mainly meet the high-end needs of information and communication technologies, and the rest of the market (14, 28 or 55nm and beyond), which is more than sufficient for the automotive and arms industries.

What are the reasons for the current shortage?

There are two factors: the disruption of supply following the Covid crisis and Sino-American competition, which has led Chinese players threatened with access restrictions by the United States to build up stocks. Regarding the Covid crisis, the phenomenon started at the end of 2020 in the automotive industry. These difficulties could last at least until mid-2022. Moreover, the automotive industry consumes $110bn-worth of semiconductors per year. But the shortage has spread to some extent to the smartphone and connected object sector.

Finally, in terms of stockpiling, we can mention Huawei, which purchased 13 billion semiconductors in 2019. The behaviour of other Chinese players threatened by the United States from 2019–2020, such as ZTE or SMIC, is not quantified but it is logical that they also sought to build up stocks to anticipate possible restrictions that were adopted by the Department of Commerce in the second half of 2020.

There is a dependence on a small group of countries. What are the strategic risks and responses of governments?

There is a move to support domestic production to mitigate interdependence. Trump gave a golden opportunity to Taiwanese company TSMC, now building a huge factory in Arizona. Biden is asking Congress for $50bn to support the industry, too. The Europeans realised the importance of boosting production on their own soil and will take action. But it is above all in relation to China that states and companies are positioning themselves.

China is, for once, the biggest loser because it is technologically behind the United States, Korea and Taiwan, who are in alliance to keep China two or three generations behind. To explain this, we need to understand the semiconductor value chain. Semiconductor design accounts for 47% of industry sales, and is dominated by Silicon Valley, from Nvidia to Qualcomm. There is a TSMC duopoly in Taiwan and Samsung in South Korea for the most advanced foundry processes. Closing off Chinese companies’ access to industry leaders cuts them off from certain segments of the global competition. For example, without access to TSMC, Huawei can no longer build high-end smartphones.

But China retains advantages related to its scale. TSMC has cut its ties with Huawei, instead producing the top of the range for Apple in Formosa but is investing to expand its foundry in Nanjing (China) to meet the needs of the automotive industry. And, geopolitically, TSMC is an asset for Taiwan. It is hard to imagine a US government risking the loss of access to the most advanced TSMC technologies in a worst-case scenario where China invades Taiwan.

What is preventing China from catching up?

China has leadership ambitions, but it is far from that; whilst their target of producing 75% of their own semiconductor needs by 2025, the country is currently only hitting 15% of that. Also, China no longer has access to foreign technologies and faces bottlenecks in EDA (Electronic Design Automation) and extreme ultraviolet lithography. This second technology, which allows the 7nm threshold to be crossed, is the monopoly of ASML, a Dutch company, the second largest in Europe. It is important to understand that the development of semiconductors is a race to miniaturisation. It follows Moore’s law, and for others it is very difficult to catch up technologically when they are excluded from the virtuous circles of innovation that exist between designers, producers, and their various suppliers – and you have fallen behind. China would like to buy this technology, but the current situation means they are totally deprived of it.

What is the European strategy?

Europe has high production capacities with a world leader, ASML, and are concentrating their forces on R&D. Around 20% of the European recovery plan is dedicated to digital transformation, and a new Major European Common Interest Project for nanoelectronics is due to be validated by the European Commission shortly. However, disagreements persist, notably on the choice of market segment. Thierry Breton believes that Europe must produce very high-end products, whereas manufacturers do not see how they can compete with TSMC in this market, where they have a considerable lead.

What roles do countries like Korea and Japan play in the geopolitics of semiconductors?

Each has their own strengths. South Korea, with Samsung, is in the duopoly of high-end engraving and can therefore accompany the major IT leaders in their production of innovative products. Of course, Samsung’s nano-electronics branch feeds its offer to consumers. Japan is a materials giant with companies like Shin Etsu and JSR dominating certain segments of the sector. They have different strategies, South Korea is seeking a balance between China and the United States while being forced to accept the restrictions on technology transfers put in place in Washington, Japan is much more openly playing the alliance card, and is looking to Europe to build the future.