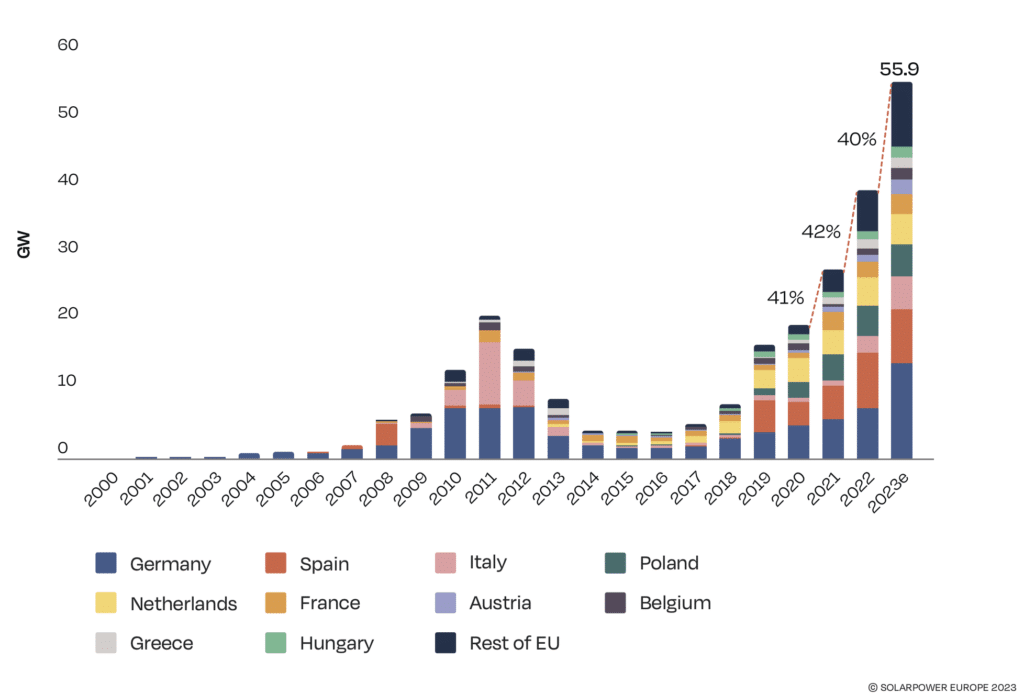

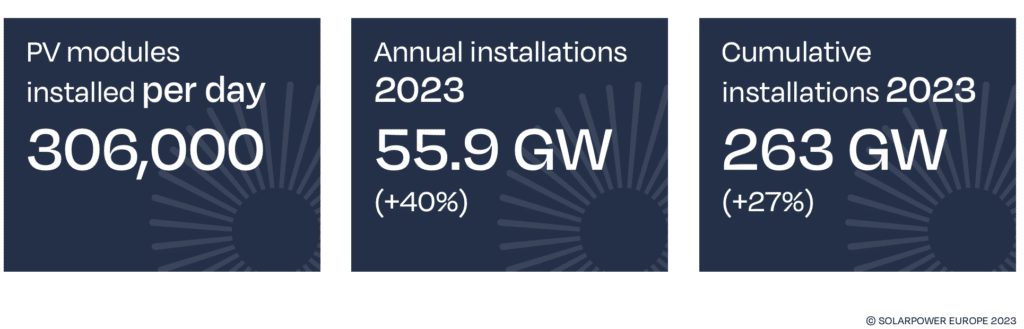

Solar photovoltaics has established itself as one of the most competitive energy technologies in the world. Between 2010 and 2023, the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) for ground-mounted photovoltaic plants fell by nearly 90%, dropping from approximately 460 dollars per megawatt-hour ($/MWh) to less than $45/MWh globally1. In Europe, installed capacity continues to increase (figure 1) and even exceeded 260 GW in 2023, with annual growth exceeding 25% (figure 2).

However, this dynamic may be covering up a more complex reality. While electricity production is almost carbon-free during operation, the environmental impacts of photovoltaics are concentrated upstream and downstream of the life cycle – extraction of critical raw materials, energy-intensive module manufacturing, land artificialisation, and end-of-life management.

Hence, eco-design is a central strategic lever for reconciling massive deployment, environmental sustainability, and territorial acceptability. This article offers a structured reading of contributions from academic literature and empirical lessons from a research project on ground-mounted solar farms, to identify the most robust and operational eco-design levers.

Optimising manufacturing and end-of-life

Contrary to a still widely held view, reducing the environmental footprint of a photovoltaic plant does not mean increasing its cost. Reference studies show that simple design adjustments can reduce environmental impacts. This mitigation ranges from 1% to 13%, for an additional cost below 0.1% of LCOE2.

The most effective levers concern classic parameters of plant design—the ratio between the direct current (DC) peak power of the solar panel and the alternating current (AC) nominal power of the inverter, row spacing, panel tilt, or reduction of electrical losses—arguing for a multi-criteria approach integrating eco-design from the outset.

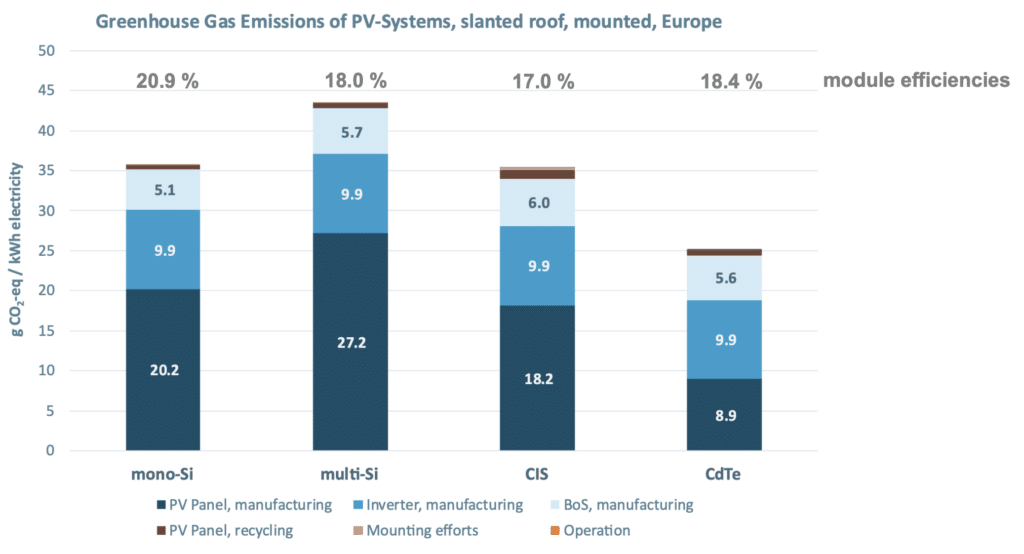

The real environmental hotspot lies in module manufacturing.The literature is unambiguous: approximately 70% of a solar farm’s carbon footprint comes from the manufacturing of photovoltaic panels3 (figure 3).

The main determinant is not so much the final yield as the electricity mix used for silicon production, with the purification phase remaining by far the most emissive. This observation explains why the most powerful eco-design levers are located upstream, at the industrial and territorial level, far more than at the level of plant sizing.

End-of-life management: a territorial and technological issue

Research on the circular economy shows that solar panel recycling, taken in isolation, is not a miracle solution. Beyond approximately 80 km between a plant and a processing facility, the environmental benefits of recycling can be cancelled out by the impacts of transportation4. Conversely, eco-design measures—demountable design, material mass reduction, thin cells—generate environmental gains up to four times greater than those obtained by merely increasing recycling rates5. These research findings lead to a structuring conclusion: the eco-design of solar farms cannot be conceived independently of project location, material flows, and territorial recycling sectors.

To understand how eco-design translates into solar farms, our research relied on in-depth analysis of several ground-mounted photovoltaic plants, without battery storage, located in Europe and North America. All the projects studied were sufficiently advanced—in operation or in the development phase—to allow feedback on design choices and their environmental, economic, and territorial effects.

The study cross-referenced technical and documentary data (impact studies, design documents, scientific literature) with direct exchanges with project stakeholders, to go beyond stated intentions and analyse actual eco-design practices. This comparative approach made it possible to identify, across cases, recurring levers, but also highly differentiated strategies depending on local contexts.

Five solar farms illustrate these contrasting trajectories.

- At Caen-la-Mer, photovoltaics becomes a tool for urban rehabilitation, giving new use to a former polluted industrial brownfield through reversible design choices and careful landscape integration.

- At Gramat, on a former landfill, the plant combines sheep grazing, pollinator-friendly meadows, and wildlife-friendly features, showing how a solar project can contribute to progressive ecological restoration.

- At Tresserre, agrivoltaic viticulture reveals solar’s potential as a climate adaptation tool, with measured reductions in irrigation needs and better crop resilience to extreme heat episodes.

- Across the Atlantic, the Eagle Point Solar project in Oregon pushes the co-benefits logic further by integrating biodiversity, beekeeping, and soil regeneration while going beyond the simple impact reduction logic.

- Finally, at Aucaleuc, on a former military site, eco-design also plays out on the social terrain, through strong local consultation, participatory financing, and educational features reinforcing the project’s territorial anchoring.

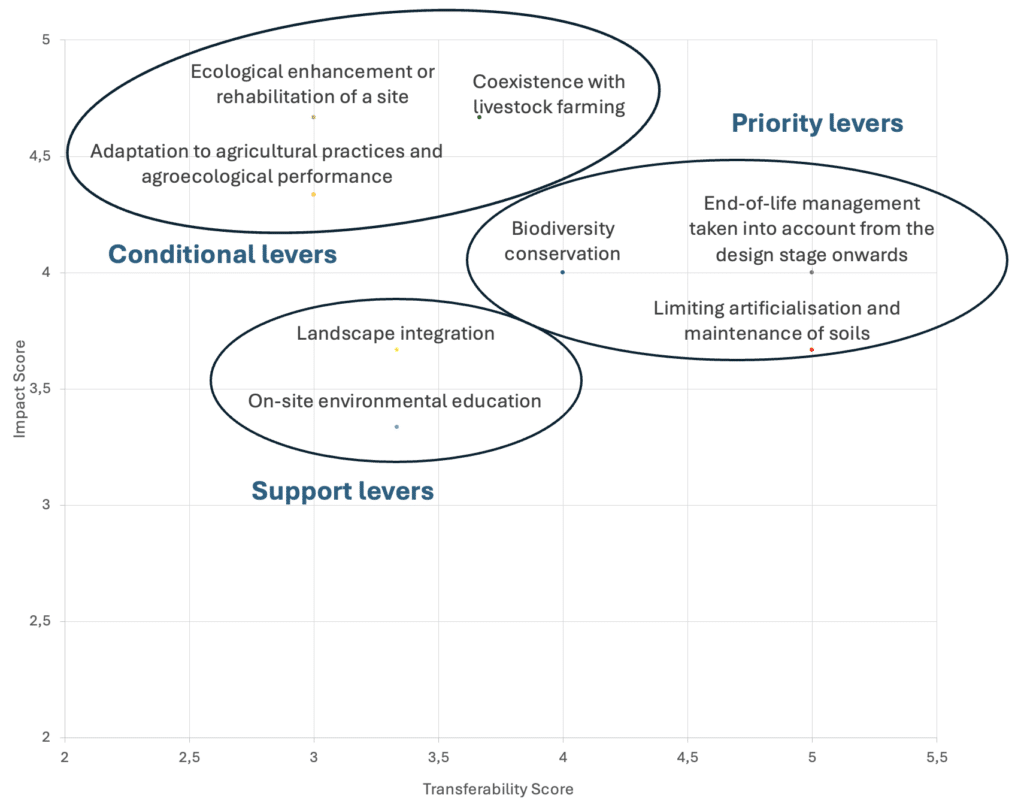

Cross-analysis of these projects identified eight similar eco-design levers but mobilised very differently depending on context. These levers were then prioritised according to two simple and operational criteria: their level of impact (environmental, economic, and social) and their ability to be replicated in other territories. This cross-reading highlights a key lesson: some actions fall under generic principles applicable to any solar project, while others only make full sense in close interaction with local specificities.

These levers were then positioned along two axes—impact and transferability—making it possible to distinguish several categories (figure 4). First, priority levers, such as end-of-life and land management, applicable to all projects. They resonate directly with industrial expectations, such as supply security and reduced dependence on virgin materials, as well as with regulatory requirements like EPR and NZIA. End-of-life management already benefits from mature sectors, notably SOREN for the recycling and recovery of metals and concrete. It is applicable to all plants and offers a direct benefit in terms of circularity and waste reduction. Limiting land artificialisation, which involves anchoring on driven piles, the absence of concrete slabs, overhead cabling, and maintaining vegetation cover, is now a standardized practice guaranteeing the reversibility of installations and better local acceptability.

Next, very powerful conditional levers, but context-dependent, such as agrivoltaics and brownfield rehabilitation. The rehabilitation of industrial, military, or landfill brownfields maximises the avoidance of land artificialisation and ecological enhancement, but this type of land is rare, which limits transferability. Cohabitation with livestock and viticultural agrivoltaics offer strong socio-economic potential by enabling the maintenance of agricultural sectors and added value for production, but remain dependent on specific agricultural contexts, such as livestock areas or vineyards. They also require close dialogue with local stakeholders.

Finally, support levers essential for social and territorial acceptability. Biodiversity preservation through habitats, reasoned mowing, and herbaceous cover remains essential, but its effect strongly depends on local ecosystems and specific measures. Landscape integration improves social acceptability, but its direct ecological impact remains limited. Environmental education has strong symbolic and social value in terms of pedagogy and awareness but contributes little to the overall performance of solar farms.

Eco-design as the foundation of tomorrow’s solar

The combined lessons from literature and case studies converge toward a clear message: the eco-design of solar farms can no longer be considered an optional supplement. It now constitutes the technical, environmental, and territorial foundation of photovoltaic deployment.

The most robust projects are those that:

- Structure universal levers (reversibility, end-of-life, land sobriety),

- Activate territorialised levers when context permits,

- Integrate local governance and acceptability from the design phase.

As solar becomes a major infrastructure for territories, its legitimacy will rest on its ability to produce energy while preserving soils, resources, and ecosystems. Eco-design is no longer a constraint: it is the strategic vector for long-term photovoltaic sustainability.