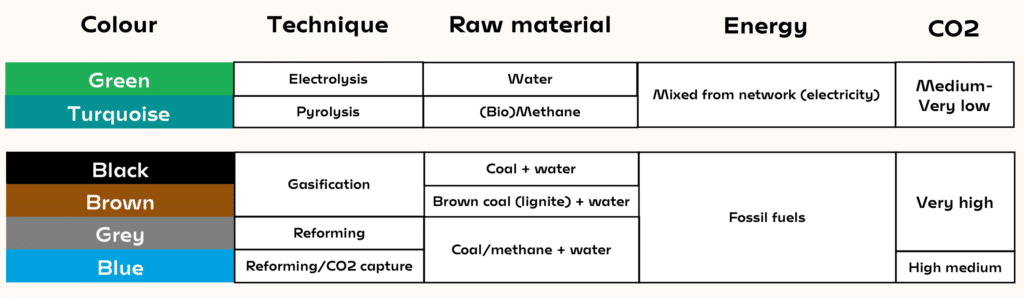

“Turquoise hydrogen” a viable solution without CO2 ?

- Black, brown and grey hydrogen are made from fossil fuels, and blue hydrogen is a similar process combined with CO2 capture and storage to reduce emissions.

- Green hydrogen is produced via electrolysis of water, but it requires large amounts of electricity from the grid or renewable energy.

- Turquoise hydrogen uses both electricity and methane, but with 4–7.5 times less electricity than electrolysis depending on the technology used – making it a hopeful technology for the future.

- Moreover, if the methane comes from biogas it has captured CO2from the air, meaning it actually has a negative carbon footprint.

Though the use of hydrogen energy is clean, its production is highly polluting, particularly when it comes to CO2 emissions. Greener solutions, such as electrolysis, do exist but they are still too expensive. Nevertheless, new, efficient low-emission technologies are emerging, such as methane pyrolysis. Here is a quick rundown of the colours of hydrogen: grey, blue, green or turquoise?

Is hydrogen the ideal energy solution?

Hydrogen is inherently a ‘clean’ energy: when you burn it or you use it in a fuel cell, it only produces water and energy. However, it is almost non-existent in gaseous form on Earth so it must therefore be produced somehow. Unfortunately, hydrogen production requires a lot of energy, which makes it far less clean. As such, today about 95% of hydrogen is made from fossil fuels. Producing 1 ton of hydrogen results in 10 tons of CO2 emissions. It is one of the energies with the worst carbon footprint and so the challenge is to find a way of producing hydrogen without emitting CO2.

Today, this is possible thanks to water electrolysis, which represents 5% of global hydrogen production. It is called “green” hydrogen. The process involves splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen, but it uses huge amounts of electricity. Energy consumption is therefore inevitable: the chemical reaction requires at least 40kWh to produce each kilogram of hydrogen, if electrolysers operate at maximum efficiency. But today, their performance is only about 60% of maximum, meaning that producing 1kg of hydrogen consumes as much as 60 kWh.

“Green” hydrogen can be further classified as “pink” or “yellow” if the electricity used is produced by renewable energy, nuclear energy (both of which have low CO2 emissions) or a combination of these.

It is easy to understand why methane reforming (using fossil fuels) is the predominant method compared to electrolysis. At current electricity prices, 1kg of green hydrogen costs 4–6 €. In contrast, hydrogen produced through reforming costs less than 1€. Given the current market, a massive deployment of green hydrogen is hardly possible.

What are the options to make hydrogen production “greener”?

One of the options is to combine CO2 reforming with the capture and storage of CO2 (see our dossier on CO2 capture and storage). The scenarios show that it would double or triple the cost of hydrogen, that is a price of 2–3 €/kg. This is called “blue” hydrogen. “Grey” hydrogen is produced by methane reforming, and “black” hydrogen is made from coal.

But there is a different way. Industrial and political circles recently discovered this process, but it is not new: I have been working on it since 1995 and have based my whole carrier on this subject. Referred to as “turquoise” hydrogen, it uses both electricity and methane. It involves decomposition of methane by pyrolysis at very high temperatures (1 000 to 2 000 °C). Hence, it still requires electricity, but 4–7.5 times less than electrolysis depending on the technology used. This process produces carbon and hydrogen, but not CO2. One kilo of methane is used to produce 250g of hydrogen and 750g of carbon, a product with high added value. More importantly, this reaction requires 7 times less electricity than water electrolysis for each quantity of produced hydrogen (but it produces two times less hydrogen than water reforming per methane molecule).

How far along is industrial production for turquoise hydrogen?

This pyrolysis process is currently under industrial development in the USA, with our American industrial partner Monolith Materials. They developed a conclusive pilot between 2012 and 2017 in California and have started industrialisation. The first unit has been built and 11 other units are soon to follow. Technological problems related to change of scale have been solved, and first marketing is expected in the coming months. This unit will consume 20,000 tons of natural gas and will produce 15,000 tons of black carbon as well as 5,000 tons of hydrogen.

At first, the economic model will consist of adding value to the carbon produced, which is widely used in tyre manufacturing and sold at approximately 1€/kg. A tyre contains about 30% of black carbon, which increases resistance to wear, UV radiation or heat. In the second phase, hydrogen will become prominent from an economic perspective. Today, the technology is optimised for black carbon production (the temperature is set according to the desired grade for black carbon). In the future, it will be optimised for hydrogen production, and new applications for black carbon will need to be developed. For instance, it could be used in construction materials, road infrastructures, or even in agricultural soils. It is cheaper and safer than storing CO2!

Better yet: if the methane comes from biogas (obtained by the decomposition of organic materials, in biogas plants or landfill sites, for example), it has captured CO2 from the air. In this case pyrolysis actually has a negative carbon footprint since it reduces the quantity of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Are there other technologies for turquoise hydrogen production technologies?

Yes, but only at the laboratory or demonstrator stage. There are “liquid metal bath” methods in which methane is injected and decomposed in columns containing molten metal. Pilots were built in California and in Australia. For its part, the German industrialist BASF studies the decomposition of methane using catalysts. These are serious competitors, but they must still overcome several technological challenges.