Since the advent of the industrial revolution, the production methods and needs of our societies have reached such a threshold that it would seem almost impossible to turn back the clock. “We often hear that the energy transition is very difficult,” explains Maria Eugenia Sanin, associate researcher at Ecole Polytechnique (IP Paris). But the truth is that we have no choice.

Numerous sectors are therefore in the firing line for an effective transition. However, efforts need to focus on one of the most important sectors in terms of greenhouse gas emissions: transport (cars account for 16% of French emissions). “Transport accounts for a large proportion of carbon emissions,” says Olivier Perrin, partner in the energy, resources, and industry sector at Deloitte. “That’s why we looked at the different ways of decarbonising it.”

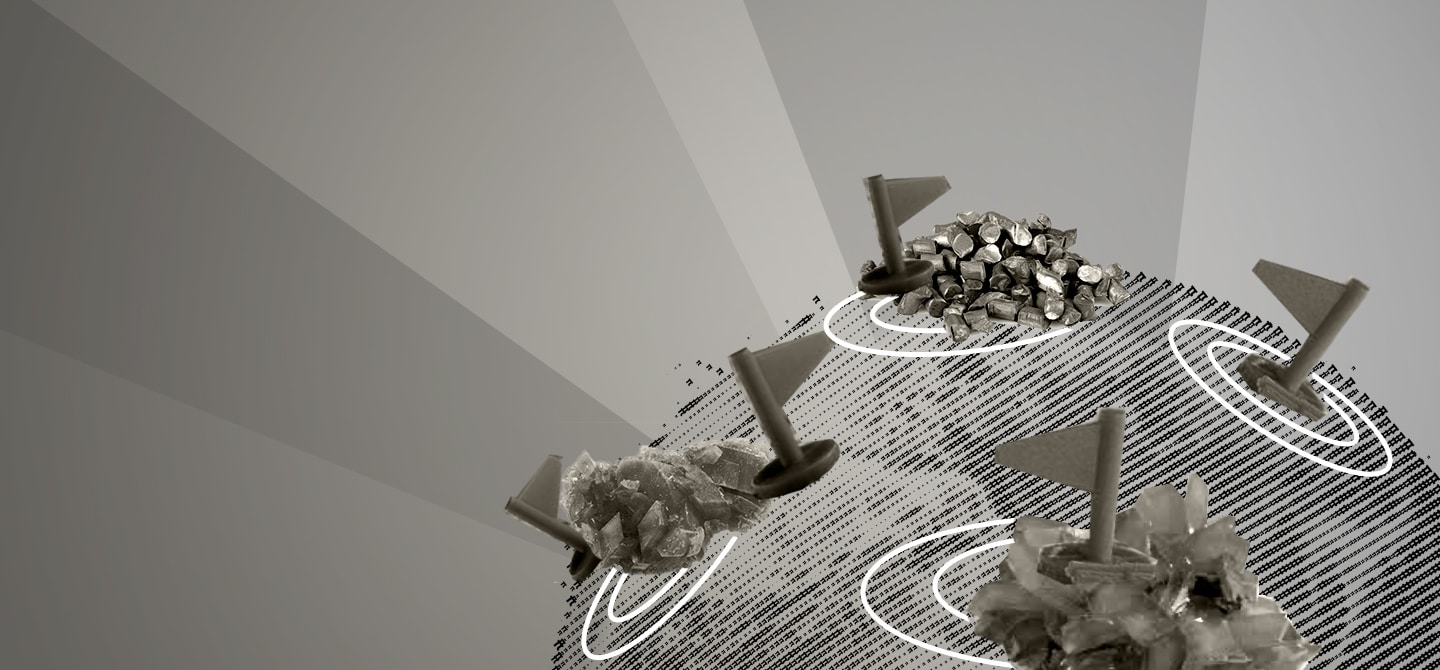

As a result, a great deal of attention is being paid to electric cars. “They say that the coming decade is the decade of batteries,” says the researcher. “But to produce these batteries, we need graphite, cobalt and, to a large extent, lithium.” If you consider the entire manufacturing process for these cars, and the raw materials required, the benefits no longer seem so obvious. From the extraction of raw materials to the final assembly of the vehicle, the move to electric vehicles raises several issues, both economic and geopolitical, not to mention ecological.

From resource extraction to electric cars

“From an economic point of view, there are three markets for raw materials,” explains Maria Eugenia Sanin. “First there’s the upstream market, then the downstream market and, in between, the midstream market.” The upstream market includes the resource extraction stage. The midstream market corresponds to the processing stage, such as refining, of these resources. Once processed, they can be used in the design of various objects, such as the assembly of batteries – this is the downstream market.

The carbon impact of an electric car is not just that of its use. The whole process, and each of the stages that make it up, emit greenhouse gases to a greater or lesser degree. What’s more, the outcome of this type of linear process depends on the stages preceding it: if the upstream market is obstructed, the downstream market cannot take place. “There is a major geopolitical issue here,” she insists, “because China dominates the upper parts of this market [the upstream and midstream markets], particularly for lithium, which is essential for battery manufacture. So, the development of other large-scale markets depends on materials that are currently dominated by a single region.”

A domination of “made in China”

There are 4 stages in the manufacture of batteries for electric cars: the first is the extraction of the various raw materials. The second is the processing (refining) of these materials. Next comes the creation of the anodes and cathodes. The fourth and final stage is the final assembly of the batteries. “When we analyse the market and take all the stages into account, we realise that we are dependent on China,” insists Olivier Perrin. “As far as ores are concerned, the global breakdown is acceptable, because we have 10 to 15 countries involved. But when it comes to processing, there’s no doubt that China is a very strong leader. As far as anodes and cathodes are concerned, China has more than 50% of the world market. When it comes to the final assembly of a battery, China has 70%.”

This geopolitical challenge is coupled with an ecological one, as China’s energy is highly carbon-intensive (over 50% comes from coal). Its industry, and therefore the electric car industry, emits a lot. “The carbon footprint from manufacture to use of an electric vehicle is quite significant,” he adds, “and the benefits compared with internal combustion cars are not so obvious. For this to be the case, the vehicle would have to be used quite extensively*.”

The tortoise and the hare

According to Maria Eugenia Sanin, “Europe has not invested sufficiently in the upper end of the market”, i.e. upstream and midstream. As a result, the supply of raw materials will not be able to keep pace with European demand. “To give an example,” she adds, “demand for lithium is projected to expand by more than 20% a year between now and 2040, while supply will not be able to expand to that level within 5 years.”

On the other hand, the European Union has recently made an effort to better equip itself for the downstream market. Projects for gigafactories – giant factories dedicated to making batteries and motors – have been launched in Europe. “Two have already opened, one in Germany and the other in France. These are still assembly plants,” insists Olivier Perrin. These plants will have to buy the components to assemble the batteries.

To break away from our dependence on China, the Deloitte consultant is pinning his hopes on recycling. “Work on the second life [recycling] of batteries is very important,” he says. “Europe absolutely must be a major player in this field.” Becoming such a player would enable the Old Continent to break away from the Chinese market. Especially given the target set for 2035 – namely that Europe will no longer produce combustion engine vehicles in its factories – Olivier Perrin maintains: “We risk seeing the end of the European automotive industry.”

The consultant believes that Europe still has a chance, provided that each of its member states acts hand in hand. “The European car industry, if it is capable of joining forces, can totally combat the Chinese, American and Japanese industries, » he asserts. If everyone goes it alone, I don’t think we stand much of a chance.”

Pablo Andres

*After publication, a factual error was corrected in this article on 1st October 2023. The original version stated that “to have an obviously lower carbon footprint than a combustion car, a vehicle would have to be used 20,000 km/year.” As this figure was incorrect, it has been deleted.