Archaea: why science is so interested in this ancient life form

- Archaea are a form of life that is genetically distinct from bacteria and eukaryotes: they make up a new category of life.

- However, they share common traits with both bacteria and eukaryotes, prompting researchers to study the relationship between these forms of life.

- Metagenomics reveals that archaea are present in all types of environments: volcanic, oceanic, terrestrial and even human.

- Studying archaea would make it possible to improve bioindustrial production systems or to imagine life forms found beyond Earth.

As soon as you read the name ‘archaea’ you may feel like you are talking about a specialised subject… But it is just another form of life, like bacteria. So why all the fuss? The answer is found in both the way they were discovered and because of the role they might have played in our evolutionary history.

An unusual life form

“At first, we referred to them as Archaebacteria, but this led to some confusion,” says Roxane Lestini, a professor at École Polytechnique (IP Paris). We need to go back to the discovery of this cell form to appreciate the misunderstanding.

Béatrice Clouet-d’Orval, a CNRS researcher at the Centre for Integrative Biology in Toulouse, agrees. “When they were discovered 40 years ago, we thought they were a special type of bacteria… They are the same size, have the same type of morphology and their DNA is not enclosed in a nucleus.” Like bacteria, archaea are only found in single cell form: they are not multicellular organisms.

These observations led scientists to believe that they were related to bacteria and not to the other known type of cells: eukaryotes. The latter group includes all animals and plants, which are made from cells that are compartmentalised and with DNA trapped inside a nucleus. Biologists at the time noted some peculiarities in archaea, such as the composition of their cellular membrane, which was made up of ethers and not esters like bacteria, without this calling into question its classification. At the very least, they were not ordinary bacteria: perhaps primitive bacteria?

With the study of genomes, we realised that these were not bacteria.

This hypothesis was swept away by the first analyses of genetic material, carried out by the American biologists Carl Woese and George Fox in 19771. “With the study of genomes, and in particular the one that codes for ribosomal RNA, which is an essential cellular machinery for life, we understood that these were not bacteria,” explains Béatrice Clouet-d’Orval. The differences between the sequences revealed that we need to consider not two but three areas of life: bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea.

Bacteria, eukaryotes, archaea… what connects these life forms?

How are these three life forms related? In 2015, this question is making progress. “A sampling study carried out in underwater volcanoes off the coast of Norway2 uncovered archaea with proteins that were only previously known in eukaryotes, for example molecules that go from the nucleus to the cytoplasm,” says Roxane Lestini. This is surprising for cells without a nucleus! “This was very controversial, many thought it was an anomaly,” says the researcher.

But other studies have confirmed these findings. “We now know that their cellular mechanisms – replisome, ribosome, genome maintenance systems, transcription mechanisms and so on – are very similar to those of eukaryotes. This is why it is assumed that archaea are involved in the evolution of eukaryotes,” explains Béatrice Clouet-d’Orval.

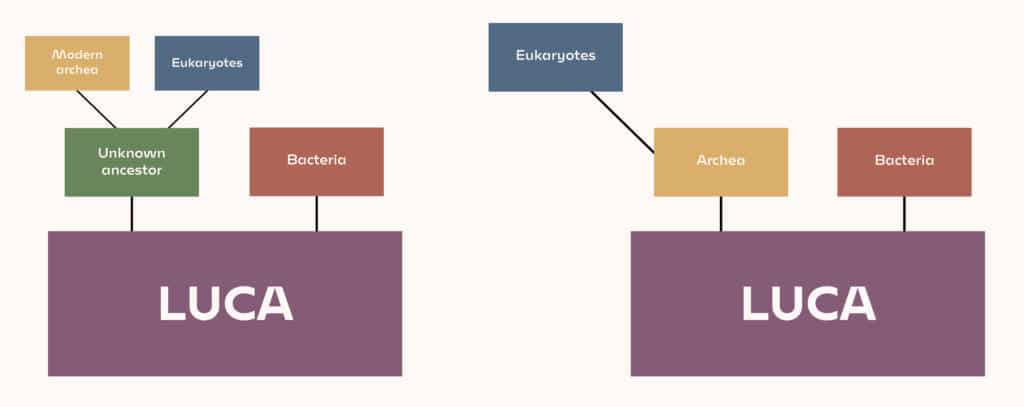

There are thus two hypotheses to describe the history of the first living cells, starting with LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor). In the first hypothesis, eukaryotes are derived from archaea. In the second, archaea and eukaryotes are derived from a common ancestor that is not known.

It is not easy to differentiate between these two hypotheses. “There are no fossils for single-cell structures,” insists Béatrice Clouet-d’Orval. “It is possible that eukaryotes are in fact archaea. What’s more, we are increasingly finding archaea that are very similar to eukaryotic cells, such as Asgards that have been discovered in the deep ocean. Their biochemistry seems to create a bridge between the first archaea discovered and modern eukaryotic cells3.”

From there, it is easy to believe that these archaea could have given rise to the first eukaryotic cell… a step quickly taken by some biologists. But Roxane Lestini points out, “nothing is certain because with unicellular organisms, horizontal gene transfers [the passage of a piece of DNA from one cell to another, from one species to another, without any relationship of descent] are frequent and confuse the evolutionary analysis of unicellular organisms”. There is still much controversy around this subject.

Archaea, everywhere

Beyond the question of origins, the molecular proximity between archaea and eukaryotes is of great interest to biologists. Roxane Lestini points out that “they are good models of eukaryotic cells, close but less complex”. But they are still quite difficult to manipulate. Béatrice Clouet-d’Orval adds, “archaea are difficult to cultivate. For a long time, this was an obstacle to their study, but today we have more and more strains adapted to the laboratory.”

It was also their natural environment that had to be revisited. “Initially, they were only found in extreme environments, such as oceanic rifts and volcanoes. But recent metagenomic tools show that they are present in all types of environments,” explains Béatrice Clouet-d’Orval. Metagenomics makes it possible to undertake a blind analysis of life forms in an environment by detecting fundamental molecules and associating them with databases of living organisms.

Recent metagenomic tools show that archaea are present in all types of environments.

This technique has also made it possible to reveal that archaea even live… in us, in our microbiota, within the microbes that populate our intestines, but also our skin, our nasal cavities and the uterus4. “There is a great phenotypic variety in archaea, and they are present in many ecological habitats,” says Béatrice Clouet-d’Orval. So, should we be concerned about these little-known microbes? “They have never been identified as pathogenic,” reassures the Toulouse researcher.

Understanding the role of these life forms in their ecosystems is another growing field of research. “We know, for example, that they play an important role in the nitrification of soils,” explains Roxanne Lestini.

As for their biological and chemical properties, they are drawing the interest of industrialists and biotechnology specialists. They are being studied to develop new PCR techniques, improve bioindustrial production systems and make sterile production safer. They are even good candidates for imagining life forms beyond Earth.