CO2 capture: will technology save us?

- Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology could prove crucial in the fight against global warming.

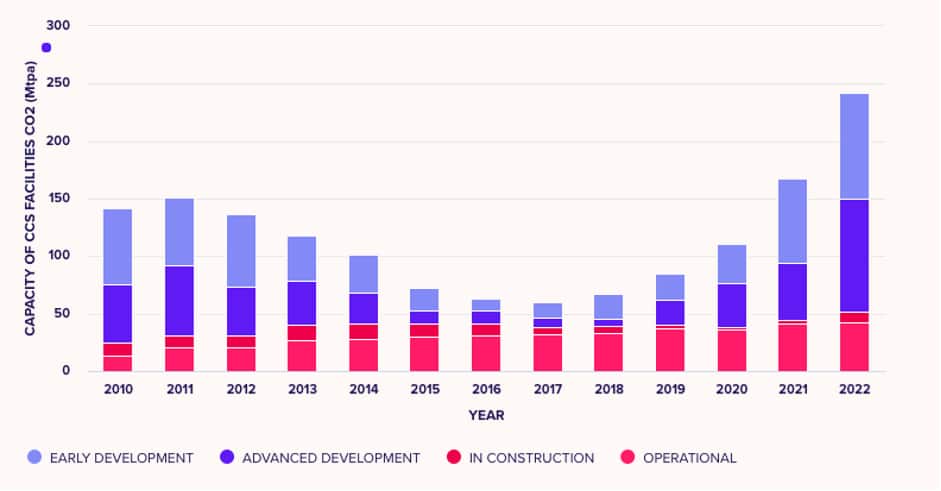

- In 2022, the total capacity of CCS projects under development was 244 million tonnes per year of CO2.

- CCS remains controversial for financial and political reasons: deployment measures are sometimes referred to as “climate inaction levers”.

- The world leaders in CCS are Canada and the United States, whose economies are based on fossil fuels.

- CCS is at the heart of international climate discussions: its development will have to be part of a comprehensive transition strategy.

Climate change is undoubtedly the most pressing issue of our time, and we are now at a pivotal moment. The effects of climate change are unprecedented in scale, from changing weather patterns that threaten food production to rising sea levels that increase the likelihood of catastrophic flooding. If we do not act now, it will be more difficult and costly to adapt to these effects in the future.

Economic benefits

From an economic point of view, we can use mitigation techniques, which, by avoiding or limiting the release of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere, reduce the severity of the effects of climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has emphasised that to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C, we need to use technologies that remove carbon from the atmosphere, in addition to stepping up our efforts to reduce emissions. One such technology, CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage), could prove crucial in the fight against global warming.

The number of CCS projects has increased by 44% since 2021.

As observers at COP27, we were able to talk to various representatives of governments and international organisations, as well as to experts in the sector. The highlight: carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology is the technological advance that is receiving the most attention. The shift from ambition to action is unequivocal, given the data on CCS investments. In 2022, the total capacity of CCS projects under development was 244 million tonnes per year of carbon dioxide. But how exactly does it work?

CCS explained

In essence, CCS involves capturing carbon dioxide produced by power plants or other industrial processes, such as steel or cement production, transporting it and then storing it underground. Saline aquifers or depleted oil and gas reserves, which are usually at least 1 km below the surface, are potential storage sites for carbon emissions. Alongside CCS is a similar idea called CCUS, which stands for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage. The concept is to recycle carbon in industrial processes by turning it into plastics, concrete, or biofuel instead of storing it.

In September 2022, the Global CCS Institute counted a total of 196 CCS projects, of which 30 were already operational and 153 were still under development. The number of CCS projects has increased by 44% since 2021, continuing the upward trend in CCS projects under construction that began in 2017. The past 20 years of experience have highlighted the diversity of applications for CCS and its key role in managing emissions from industrial processes.

Through the CCS networks, we expect to see an increase in strategic alliances and collaboration to drive implementation. With several blue hydrogen projects under development around the world, clean hydrogen and other low carbon fuels are also part of the growth of CCS. Direct Air Capture with Carbon Storage (DACCS) has also seen an increase in interest and participation this year, with billions of dollars in funding earmarked for scaling up this technology.

A solution for ecological transition at the expense of emissions reduction?

Although promising, these technologies remain controversial, notably for financial and political reasons. Indeed, the economic effort deployed for the development of these strategies is considerable, for results that are certainly promising but still uncertain. Moreover, by concentrating efforts on carbon sequestration technologies, it is possible that those involved in the ecological transition will sideline the issue of emissions reduction, so much so that policies geared towards the deployment of CCS are described by their detractors as “levers for climate inaction”.

The deployment of CCS cannot be achieved without government intervention, which makes it a highly political issue.

CCS infrastructure is expensive, which makes it difficult to attract investors, especially as the benefits are not always evident. For example, in the United States, 11 CCS projects had been undertaken by the Department of Energy by the end of the 2000s, eight of which were in the coal sector at a cost of $684 million. Of these eight projects, only one was completed and operational from 2017 to 2020. In Europe, CCS projects are also on the rise, with northern European countries (Norway, the Netherlands, and the UK) announcing more than €5bn to be invested in CCS.

According to an Ifri report, the cost of CO2 capture, transport and storage is between €40 and €200/tonne with currently available technologies – the higher end of this range corresponding to particularly polluting infrastructures such as power plants and waste incineration plants. This cost, although decreasing with the evolution of the technology, remains higher than the price of CO2 on the carbon market, undermining the incentives for private actors to invest in CCS.

Deployment of CCS cannot therefore be achieved without government intervention, which makes it an highly political issue. The question of public investment in CCS says a lot about countries’ or regions’ strategies for achieving the 1.5°C target set by the Paris Agreement, and about their vision of the ecological transition.

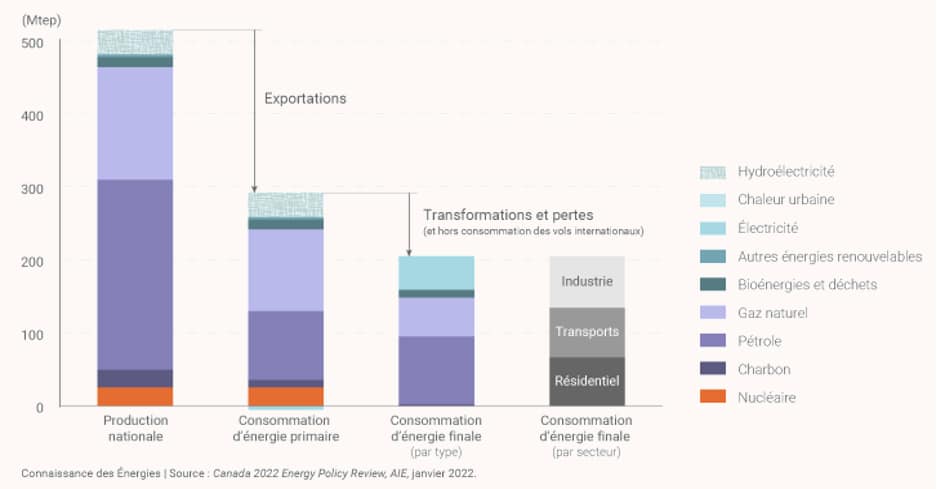

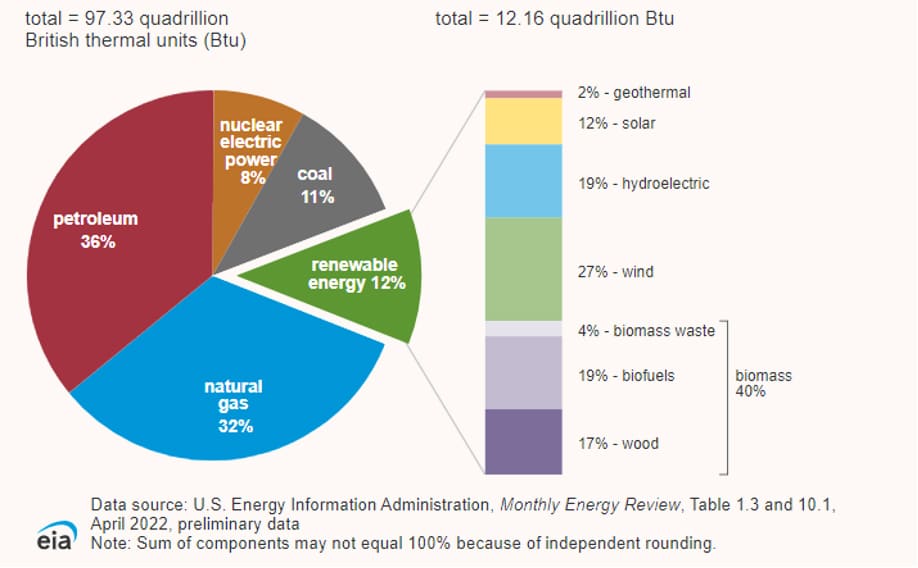

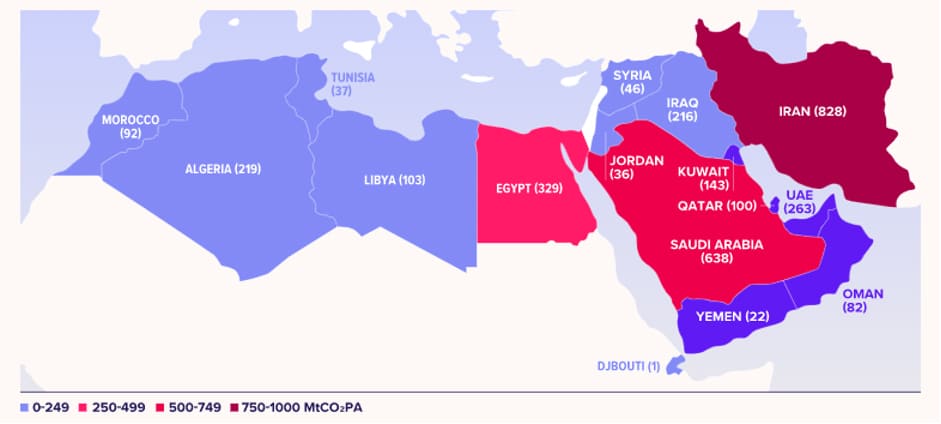

The leaders in CCS today are the states and actors whose economies are based on fossil fuels: in Europe, for example, CCS are mainly promoted by policymakers in countries whose energy mix is mainly based on oil and gas. In the world, the leading countries for these technologies are Canada and the United States, which also have a highly concentrated energy mix. During the COP27 negotiations, the Gulf States, and in particular the United Arab Emirates, also showed their enthusiasm for CCS, which was presented as one of their main levers of action for achieving the objective of Zero Net Emissions by 2030.

In the private sector, the main supporters of CCS development are also oil companies: ExxonMobil and Big Oil in the United States, TotalEnergies and Technip in France, which are suspected of using their investments in CCS as a means of diverting public attention from their oil and gas activities to preserve them. Indeed, COP27 was strongly marked by the presence of oil and gas producers, who were 25% more numerous than at the previous COP in Glasgow. The CCS was at the centre of their discourse on their strategy to decarbonise their activities.

On the road to COP28

Countries such as Qatar, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Saudi Arabia are among the top ten per capita carbon emitters. As a result, the Middle East, and North Africa (MENA) is considered one of the most greenhouse gas intensive regions.

In Sharm, discussions of our hopes for technology revolve mainly around CCS. Interestingly, one of the main players on the international scene promoting this technology is the United Arab Emirates, which will host the Conference of the Parties in 2023.

As a technology with great potential, CCS is in any case central to international discussions on the climate issue, and its development will need to be part of a comprehensive transition strategy with clear and concrete objectives.