Eating fewer animals reduces emissions, but by how much?

- Food production is responsible for around a quarter of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

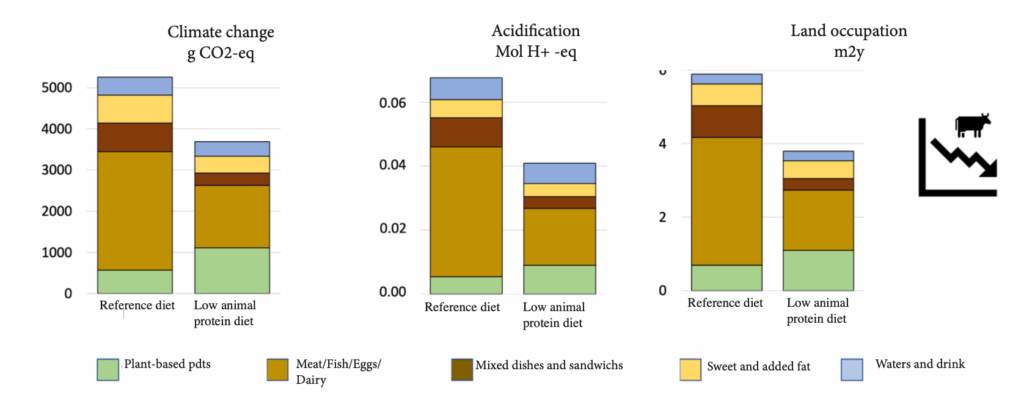

- A reduction in animal protein consumption among adults in France could lead to a decrease of the impact of food on climate change, acidification and land use.

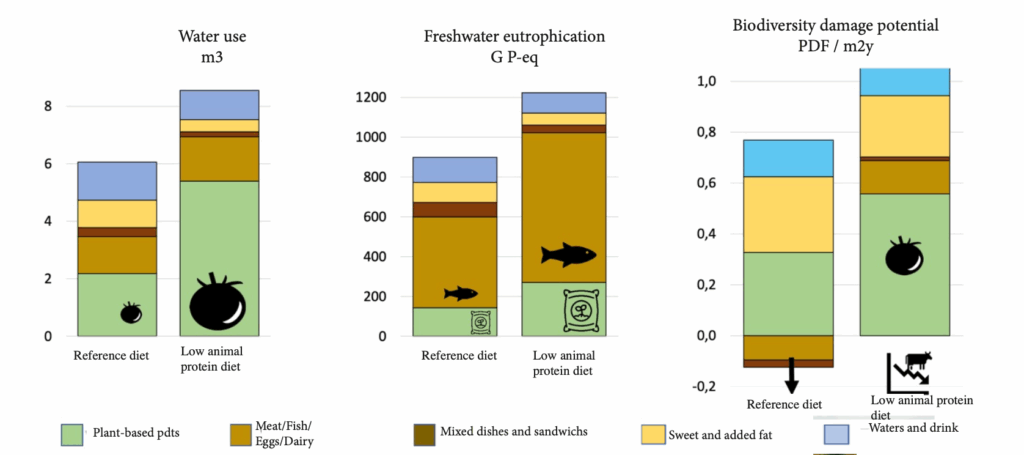

- However, this lower animal consumption could have a negative impact in terms of water use, freshwater eutrophication and biodiversity.

- This is because a diet low in animal protein contains more plant-based foods and is more dependent on water-intensive irrigated crops in our societies.

- Nevertheless, this research does not contradict the positive impact of a diet lower in animal products on the climate.

Agriculture is one of the key levers for mitigating climate change: food production is responsible for around a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions. Livestock farming and fishing are the main contributors to these emissions. As detailed in a report, it is clear that reducing emissions from agriculture requires a reduction in our consumption of animals. From a nutritional point of view, a plant-based diet is beneficial to health, often to a greater extent than suggested by health recommendations, which take into account parameters such as cultural norms and feasibility in the general population, as explained by François Mariotti. In a study published in early 2025, Joël Aubin and his colleagues looked at the other environmental benefits of reducing animal product consumption in France1.

What are the main findings of your study?

Joël Aubin. We are assessing the environmental impacts of a reduction in animal protein consumption among adults in France over their entire life cycle. This includes all emissions linked to the production, processing, transport, consumption and end-of-life of products.

Compared to an average diet, the diet considered here contains less protein overall (with a reduction from 80 to 70 g per day) but also a lower proportion of animal protein. The daily amount of animal protein is thus reduced by about 20 g. This choice is based on health recommendations but also on the desire not to increase the cost of food by more than 5%.

Our study shows that if the French adopt this low-animal-protein diet, the impact of food on climate change, acidification and land use will decrease. On the other hand, there will be an increase in the impact on water use, freshwater eutrophication and biodiversity.

How do you explain these negative impacts on the environment?

This diet, which is low in animal protein, contains much more plant matter. It is therefore more dependent on irrigated crops that consume a lot of water, at least with our current production methods. In terms of biodiversity, the proportion of beef in our low-protein diet is falling sharply. However, cattle are the species that make the most use of grasslands, which leads to a very high loss of pastureland, an important source of biodiversity. Added to this is the need to increase certain agricultural areas to meet food needs.

Can’t the land freed up by the decline in livestock farming, particularly cattle farming, be used to grow these plant products?

On a global scale, reducing livestock farming would allow almost a third of the Earth’s land area to be reclaimed. But would replacing the land used for livestock farming be enough to meet food needs? There is no scientific consensus on this issue. Finally, there are two limitations. The first is that not all grassland is suitable for cultivation, and converting it to low-yield crops would increase the environmental impact of plant production. Finally, it would be necessary to ensure that grassland is replaced by crops for human consumption, rather than urbanised areas.

This is only a partial study and did not aim to examine all the indirect consequences of this change in diet, so the repurposing of grasslands to crop production is not considered. Of course, if this were the case, the impact of a diet low in animal protein on biodiversity would be reduced.

Is it possible to limit these negative externalities?

Changing agricultural practices, particularly agroecology, is an effective mitigation solution. Replanting hedges, rotating crops, reducing pesticide use, reducing plot sizes, etc. All these practices help to limit our dependence on natural resources and restore the ecological functions of environments.

Do your findings call into question the climate benefits of a more plant-based diet?

No, our work does not contradict the positive impact of a diet lower in animal products on the climate. Our diet reduces greenhouse gas emissions by around 30%, despite a relatively small reduction in animal protein intake. Our study highlights the need to consider all the consequences of societal choices.

It is important to understand that these negative externalities do not call into question, but rather limit, the environmental benefits of reducing the proportion of animal products in our diets. However, identifying these negative impacts should make it possible to limit them.

Are there any regions of the world where a more plant-based diet has already proven its environmental benefits?

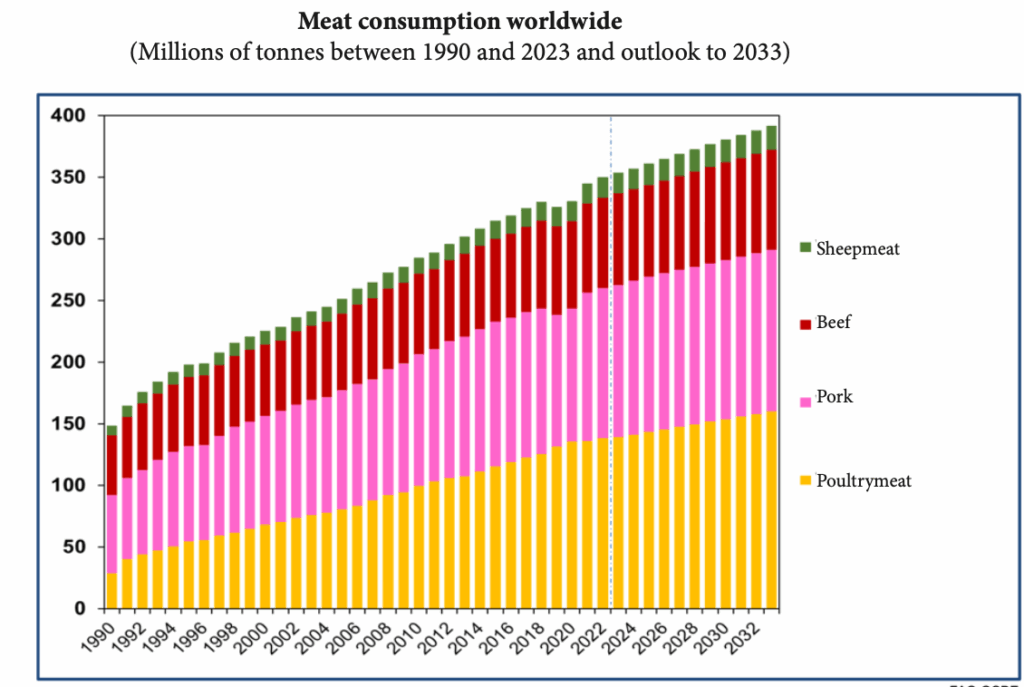

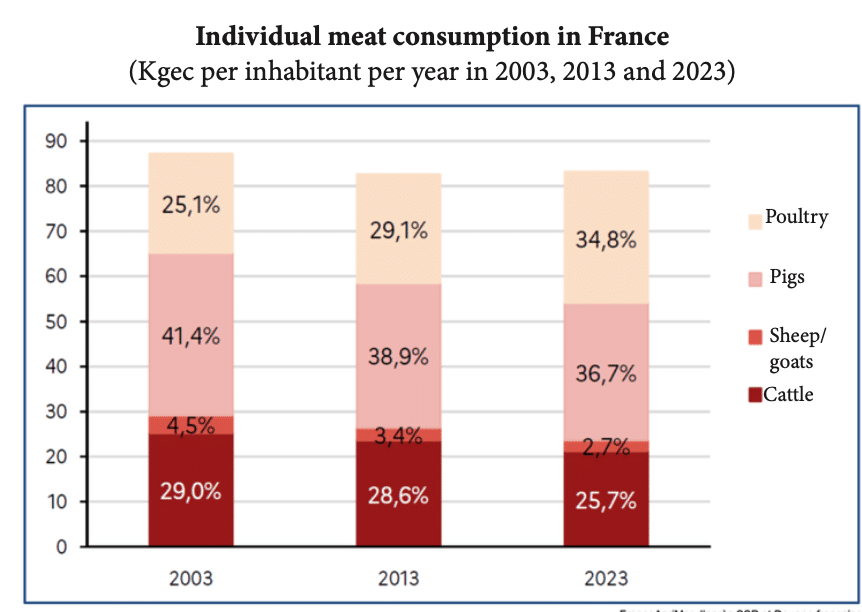

No, because despite what we may think, the consumption of animal products is not decreasing globally, nor in France. However, we are seeing a shift in consumption, with an increase in the consumption of pork and poultry and a decrease in the consumption of beef.

Are your findings applicable to other regions?

They are very specific to France, where most cattle are raised on pasture, unlike in the United States, for example.

This study was funded by GIS Avenir Élevage – a consortium of stakeholders in research, training, development and the livestock sector – and INTERBEV – the national interprofessional association for livestock and meat. Did this influence the results?

We are scientists, and we are committed to producing robust knowledge without external influence. The fact that our article was accepted for publication in a scientific journal shows that these results are reliable. However, it did give us access to databases. For example, the French diet is based on more than 250 indicators. Access to this data has enabled us to study these impacts on water and biodiversity in a way that has never been done before.