There’s a type of mayfly whose females emerge, mate, lay their eggs and die in under five minutes. At the other end of the longevity spectrum, sharks swimming in the frigid waters around Greenland have been estimated to live 400 years. The diversity of lifespans in the natural world is as incredible as the range of sizes, shapes, diets and lifestyles found in living creatures. So, what can we learn from animals about how to age well ourselves?

1. Worms

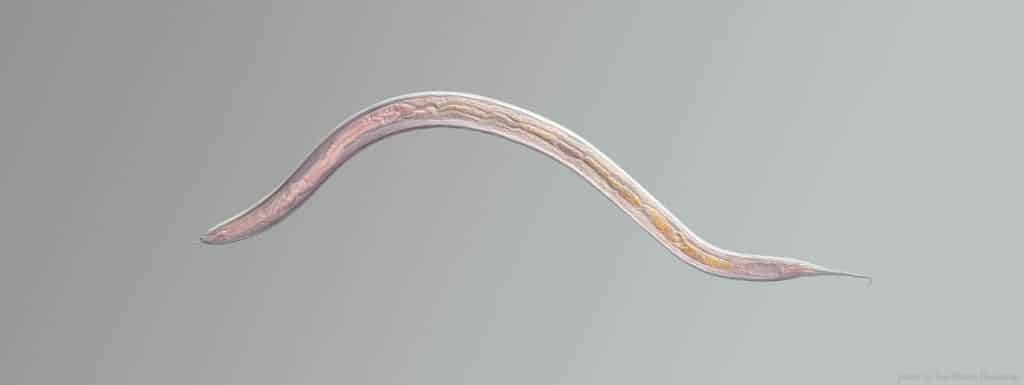

At around a millimetre long and almost transparent, you’re probably going to need a microscope and some help to spot C. elegans, the scientific name for an unassuming nematode worm that has become one of the stalwarts of ageing research. These nematodes were originally found by scientist Sydney Brenner in his compost heap1, because he was looking for a new ‘model organism’—a creature which shares enough biology with more complex animals, including humans, to learn what makes us tick, but is easier to work with in the lab.

Worms have lots of advantages when it comes to longevity research: being so tiny, you can grow hundreds of them on a tiny plate in the lab, and their natural lifespan is just two weeks, meaning detailed experiments which would take years or decades in longer-lived animals can be concluded in just a few months.

Of their many contributions to biology research, the most remarkable thing that these worms have taught us is that even changing a single gene can be enough to dramatically extend lifespan. The first worm ‘longevity gene’ was discovered in the late 1980s, and added about 50% to worm lifespan2—but the idea that a single genetic change in a creature with 20,000 genes could extend lifespan was so outlandish that the results didn’t gain much traction. A few years later, another gene was found that doubled worm life expectancy, from two weeks to four3—and this even more striking result, in a totally unrelated gene, caused scientists to sit up and take notice.

There’s now a huge back-catalogue of genes that can increase lifespan: over 600 in C. elegans, and hundreds more in other organisms4. For example, the world’s longest-lived mouse didn’t have the perfect diet and exercise regime, or some miracle drug—the ‘Laron mouse’ has a single mutation in a gene related to growth hormone, and the reigning longevity champion died just a week short of its fifth birthday, where normal mice rarely live more than three years5.

2. Opossums

Why do worms only live for 14 days and mice a few years, while Greenland sharks can live to 400? Indeed, why do creatures grow frail and die at all? Evolution is often summarised as ‘survival of the fittest’—so why does it permit us to grow old and die? Enter the opossum, an American marsupial that looks like a mouse the size of a cat, that provided a serendipitous confirmation of how this can happen in the wild.

Ecologist Steve Austad started studying these critters when they kept wandering into a colleague’s traps intended for tropical foxes. He decided not to let the unintended captives go to waste, and tagged them with radio collars. But, as he continued to study them, noticed something remarkable: the incredible speed at which they aged. Animals would turn from fully-functional adults to decrepit or deceased over a matter of months.

Why do opossums suffer such a rapid fall from fitness? The answer, unfortunately for them, is that they’re delicious. Imagine life from the perspective of one of those fast-ageing opossums: as a docile, cat-sized mouse, you’d make a great snack for a predator (like those tropical foxes Austad’s colleague was trying to catch). As a result, more than half of wild opossums meet their end in the claws or talons of another creature. Opossums, then, age so rapidly because of an evolutionary trade-off6: there’s no point staying fit and healthy until the age of 10 if you’re almost certain to be eaten in your first three or four years. Instead, evolution concentrates an opossum’s energies on having lots of babies before predators devour it, not worrying about whether its body will fall apart should it somehow dodge becoming someone’s dinner.

Thus, Austad theorised, if he could find a population of opossums somewhere without predators, evolution might take a different tack: grow up and grow old at a more leisurely pace, not rushing to literally and metaphorically outrun predators by having kids as fast as possible. He did indeed find such a place: Sapelo Island, just north of Florida, which, after separating from US mainland 4,000 years ago, lost its big carnivores. And 4,000 years may be a long time by human standards, but it’s brief enough evolutionarily that this provides an opportunity to watch natural selection in action.

What he discovered on Sapelo was a population of fearless opossums—unlike their mainland counterparts who were nervous and nocturnal, they’d walk around in plain sight during the day. And, where mainland opossums had a maximum lifespan of 2.5 years, Sapelo’s fearless versions could live for nearly four7. Over perhaps a couple of thousand opossum generations, an elegant natural experiment had shown us why we age: because thrifty evolution won’t invest the resources to keep you alive if you’re likely to be dead from another cause anyway.

3. Whales

While moving to a predator-free island and gradually breeding longer lived humans over thousands of years might sound like something from a dystopian sci-fi novel, the lesson from opossums can lead us to something more actionable. If you want to find really long-lived animals, find those at low risk from predators—and perhaps we can learn something about longevity from their biology.

A great example is the bowhead whale. At 100 tonnes, these are some of the largest animals ever to have lived and, correspondingly, very rarely eaten—a handful of reports document pods of orcas attacking bowheads, but their main threat was the barbaric whaling industry, which is thankfully now largely a thing of the past. As a result, these ocean giants evolved one of the longest lifespans in nature—the oldest whale ever recorded was estimated to be 211 years old8.

Animals so huge as to be effectively inedible also having incredible lifespans accords precisely with evolutionary expectations—but presents something of a paradox when considered on a cellular scale. The size of a cell is more or less constant whether you’re a human, a mouse, or a 100-tonne whale, which means a bowhead has approximately 1000 times as many cells as a person does, and they also live at least twice as long. The conundrum this leads to is simple: why aren’t all bowhead whales absolutely riddled with cancer?

Cancer is caused by random mistakes appearing in a cell’s genetic code. That’s one reason that cancer is a disease of ageing: the longer you’ve been alive, the more time these genetic typos have to accrue. It also means that every cell is a risk, so having 1000 times as many cells should substantially increase your chances. And yet, whales don’t seem to be giant, swimming tumours. What’s their secret? One suggestion has come from rummaging around in the bowhead whale’s genetic code: they have additional copies and subtle variations on genes responsible for DNA repair9, perhaps meaning that their cells are more vigilant to mutations that could give rise to cancer. As well as being cancer-resistant, bowheads also don’t seem to get cataracts, the clouding of the lens of the eye that affects many animals (including humans) as we age, perhaps due to antioxidant chemicals in their lenses10. And making it to such incredible ages requires that whales dodge or postpone all the major ailments that make our lives miserable long before we reach 200 years old. Whales are a tough animal to study in the lab, but their biology almost certainly harbours a few longevity tips and tricks that we’d do well to go fishing for.