Rudolf Clausius: the scientist who helped us understand the climate

- The Clausius-Clapeyron formula is cited 36 times in the 2021 IPCC report: to understand its importance, we need to go back in time.

- The history of the climate study goes hand in hand with the study of the oceans and the atmosphere: it was in 1824 that the concept of the greenhouse effect first appeared.

- Émile Clapeyron was one of the first people to formulate the second law of thermodynamics and the formulation of the law of perfect gases (PV=nRT), among others.

- The Prussian Rudolf Clausius then took Clapeyron's formula and applied it to a liquid-vapour equilibrium.

- The result is the Clausius-Clapeyron formula: an increase in temperature of 1°C corresponds to an increase in atmospheric humidity of about 7%.

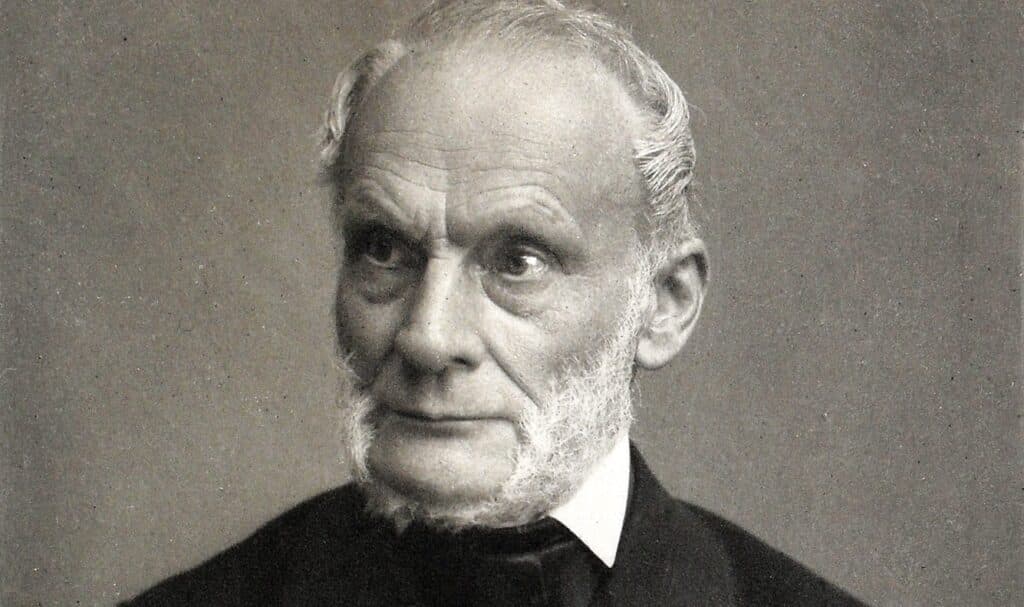

In August 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published the first part of its Sixth Assessment Report1, which focuses on the physical sciences that underpin our understanding of climate change. The purpose of the IPCC reports is to assess recent scientific publications, extract a scientific consensus and produce a text for policy makers. In this report, the name of Rudolf Clausius (1822–1888), whose bicentenary is being celebrated this year, is mentioned several times.

To understand how such a sophisticated science as climatology originated and developed, we need to go back a few centuries.

The ocean as point of origin

The history of the study of climate runs parallel to the study of the oceans, which play a central role in climate regulation. The geography of the sea, as oceanography was once called, is a very old discipline that grew out of the economic interest in bodies of water for trade, fishing, whaling and exploration. Until the 16th Century, however, knowledge was acquired through anecdotal information based on fishermen’s tales and maps, sometimes accompanied by esoteric or magical explanations.

To understand how a sophisticated science like climatology came into being, we have to go back a few centuries.

Critical to the understanding of atmospheric and marine conditions were the inventions of the thermometer and barometer, which took place between the 16th and 17th Centuries in Italy (thanks in particular to the work of Galileo and then Evangelista Torricelli).

Knowledge of the oceans, and in particular the mapping of currents, was hampered until the mid-18th Century by an inability to determine longitude at sea. The development of marine chronometers enabled current mapping to begin, initiated in particular by Benjamin Franklin.

Oceanography, as a scientific discipline, was born between 1855, the year of publication of the Physical Geography of the Sea by the American Matthew Fontaine Maury, and 1872, the date of the start of the first oceanographic campaign, the Challenger expedition by the Scot Charles Wyville Thomson.

Then the atmosphere

In France, in 1774, Abbé Louis Cotte – who worked for the Royal Societies of Medicine and Agriculture – published the Traité de météorologie2, which is now considered one of the first texts on modern climatology.

But it was at the beginning of the 19th Century that the study of the atmosphere and the gases that it is made up of became more complex. The concept of the greenhouse effect first appeared in 1824, in a publication by Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier, who was studying the mathematics of heat flows3. This great physicist and mathematician from Franche-Comté hypothesised that the atmosphere acts as an insulator, without which the Earth would be completely frozen.

More information was needed on the role of the atmospheric gases behind the greenhouse effect. In 1861, in the midst of the heated debate about the origin of the ice ages, the Irish physicist John Tyndall – Michael Faraday’s successor at the Royal Institution and a keen glaciologist – discovered that the primary gas involved was water vapour, followed by carbon dioxide (CO2)4. These gases absorb some infrared radiation, and small changes in their concentration cause climate change. Similar, though less successful, results had been obtained five years earlier by the American inventor and women’s rights activist Eunice Foote, but there was no dissemination beyond the ocean and these early results were subsequently forgotten5.

Then the direct link between the carbon cycle and the Earth’s temperature was demonstrated by Nobel Prize winner Svante Arrhenius. The Swedish chemist demonstrated that an increase in CO2 in the atmosphere results in a significant temperature increase6. He calculated that if the concentration of atmospheric CO2 were to double, the average temperature would have risen by 4°C to 6°C, which is not far from current estimates. It is a pity that the scientific community only accepted the influence of CO2 on the atmosphere in the 1950s. Arrhenius was more far-sighted: he also realised that the increase in CO2, which was already taking place in his time, was to be attributed to the industrial use of coal and other fossil fuels. Only, as far as he was concerned, this was good news: human beings in the future would not suffer because of a new ice age!

Finally, the IPCC

Finally, let’s turn to the Clausius-Clapeyron formula, which is cited 36 times in the Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC). Emile Clapeyron (1799–1864), a student at École Polytechnique from 1816 to 1818 before joining École des Mines, was a Parisian engineer and physicist who, in the early part of his career, made significant advances in bridge engineering. It was his deep interest in the nascent railway industry that led him to work on steam engines and to supervise their construction, but he was most interested in improving the efficiency of locomotives7.

He became aware of the work of Sadi Carnot, now considered the founder of thermodynamics but little known at the time (he had just died, aged only 36). Clapeyron divulged his work on the mechanics of heat, made it more readily understandable and made an enormous contribution. He was one of the first to formulate the second law of thermodynamics, the formulation of the law of perfect gases (PV=nRT) and the graphical representation of the evolution of the pressure of change of state of a body as a function of temperature (Clapeyron formula).

Clausius took Clapeyron’s formula and applied it to the special case of a liquid-vapour equilibrium.

A few years later, another founding father of thermodynamics, the Prussian physicist and mathematician Rudolf Clausius (1822–1888), reformulated the second law of thermodynamics in its present form: “Heat is always transferred from a hotter body to a colder one”. He also introduced the concept of entropy. In addition to his teaching activities at the Zurich Polytechnic and the universities of Berlin, Würzburg and Bonn, Clausius contributed to the great discoveries in physics of the 19th century and was inspired by his contemporaries Carnot, Joule, Kelvin and Clapeyron. Indeed, Clausius took Clapeyron’s formula and applied it to the particular case of a liquid-vapour equilibrium8.

And now, Clausius-Clapeyron

Finally, we arrive at the famous formula that is so useful for studying climate change. According to the Clausius-Clapeyron formula, a temperature increase of 1°C corresponds to an increase in atmospheric humidity of about 7%, i.e. about 1–3% more precipitation on a global scale. In simple words, this equation helps to understand the formation of clouds, rain, snow and is very consistent with the prediction of extreme weather events such as increases in the frequency of precipitation and its annual maximum amount, wind speed, river flooding. Moreover, the increase in humidity corresponds to an increase in the mass of water vapour and thus in the greenhouse effect, thus leading to a positive feedback loop.

The Clausius-Clapeyron formula is therefore a very good physical basis for future forecasts, at least on a global scale. Indeed, important variations on a regional scale can occur depending on local conditions, as Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) already understood when he studied the different climatic conditions of the South American landscape.