Are modern uncertainties fragmenting our shared sense of reality?

- Previously, the myth of progress directed people’s focus towards the future and society as a whole, but today, the ideology of the present directs people’s focus towards themselves.

- According to an Ipsos survey conducted in 50 different countries, 62% of citizens agree with the idea that the present is better than the future.

- Today, the feeling of alienation from the world stems from an inability to act, such as repairing one’s phone or car oneself.

- The technological revolution and the rise of narratives that constantly question individual feelings cause frustrations that fuel a sense of unease.

- Different communities, such as shifters, therians, or hikikomoris, embody an extreme form of escape from others and from the world.

Science is under increasing attack. However, radical groups attacking universally accepted truths would have no audience if they were not in tune with a major trend in contemporary society: demanding that reality conform to our desires or feelings. Gérald Bronner, a sociologist specialising in beliefs and social representations, helps us to understand this trend.

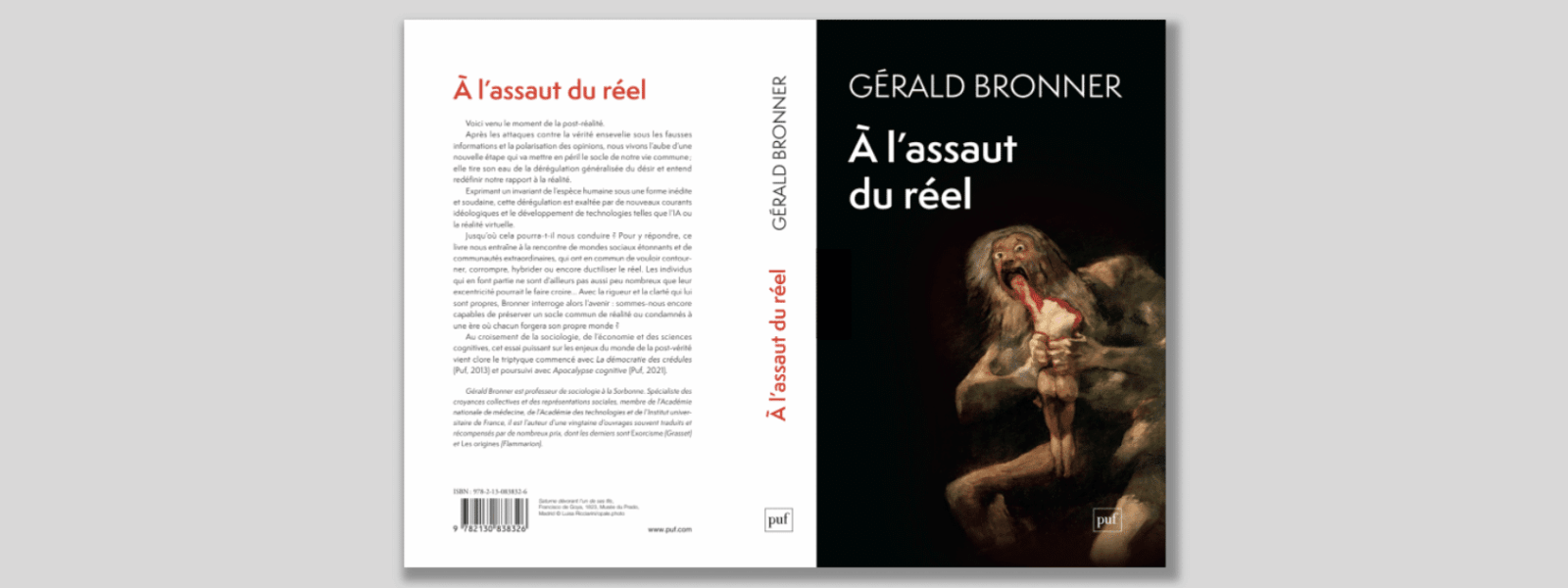

In your latest book, you write: “the present cannibalises reality”, echoing Goya’s painting “Saturn Devouring His Children” on the front cover. What are you trying to say with this?

Gérald Bronner. First, our individual perspectives – and therefore, collectively, the aggregation of these perspectives – have turned inward. In doing so, they have turned away from the distant horizon of a shared hope for the future. One of the signs of this shift is the decline in the use of the term “progress”, a decline that can be observed in all forms of literature and in many languages. Google’s linguistic application, Ngram Viewer, shows a decline starting in the 1960s, followed by an irreversible drop. Something invisible to the people of the time was happening: a departure from the myth of progress, the modern ideology that the future would be better than the present. Gradually, our personal compass refocused on the present and on observing ourselves.

Great collective adventures have been replaced by another adventure, just as exciting, but with its own pitfalls. Self-discovery, with the haunting question “who am I?” And above all, “who could I have become?” This second question responds to a vague feeling of frustration: I could have become something better, but I didn’t really optimise my potential. In this sense, why? What prevented me from doing so? Thus, alongside the decline of the myth of progress, we are seeing an obsession with personal development and the pursuit of individual happiness. This can be seen in surveys conducted by sociologists and pollsters, but also in advertising slogans and fiction. This quest is becoming increasingly important to us, and as it takes hold, the temporal dimension of our outlook seems to be shrinking.

With the exception of a past that is very close to us, when people are asked when they would like to live, they tend to answer the present

Almost no one wants to live in the future, barely 4% of our fellow citizens. And when people in 50 different countries were surveyed, as Ipsos did, 62% agreed with the idea that “the future can take care of itself, only the present matters”. There are certainly variations from one country to another, but almost everywhere, the idea that the future can take care of itself is held by the majority. Even in films and fiction, the encouragement to enjoy the present is presented as a form of wisdom. It affects our ability to be citizens who think about public interest and the common good. The present has devitalised the future. And cancel culture, this morally indignant view of our history, shows that it also devalues the past. With the exception of a past that is very close to us: when people are asked when they would like to live, they tend to answer the present and, curiously, the 1980s. The dominant feeling is what I call nowstalgia – a kind of nostalgia for the present.

Is this “nowstalgia” a nostalgia for a simpler world, as opposed to the flood of information and cognitive market disruption that you have studied in your previous works, La Démocratie des crédules [The Democracy of the Gullible] (2012) and Apocalypse cognitive [Cognitive Apocalypse] (2021)?

Certainly, with hindsight, yesterday’s world seemed more controllable, more intellectually manageable. It was not multifaceted: two blocks were pitted against each other, which allowed for a simpler moral interpretation. The camp of freedom could be placed either on the side of NATO or on the side of the Warsaw Pact, depending on one’s sensibilities. The notion of national sovereignty was also much stronger, of course. Individuals felt that political decisions were understandable and within their reach, which led to much greater confidence. There were far fewer media outlets and much less information flooding our world. There were far fewer television and radio channels, not to mention the massive deregulation associated with the rise of the Internet. Even though everyday technologies are much safer today, we can no longer directly intervene in this technological world: if my phone malfunctions, I have to replace it; I cannot repair it as I would change a light bulb or, if I were something of a handyman, the engine of my car.

All this gives a feeling of alienation from the world. And this excites a part of the democratic soul. Tocqueville already noted the tendency of democratic systems to produce frustrated individuals. This democratic melancholy is exacerbated today by two phenomena. The first is the technological revolution in the information market and in the market of cognitive objects, such as artificial intelligence, which profoundly disrupts who we are as human beings and how we view the world. The second phenomenon is the rise of these major narrative trends, which allow us to look obsessively within ourselves and constantly question our feelings.

Why is this dangerous? Quite simply because the next step is to demand that my feelings bend reality. In other words, to make others accept that the expression of my feelings is a standard of truth and reality. This affects the boundaries between our imagination and the world as it is. This is how our era attacks reality.

One of the strengths of your book is that it articulates a global vision, the one you have just outlined here, while exploring the many social groups that embody it, sometimes to the point of caricature. Can you explain this to us?

There is the face of the era, and there is its grimace. But my point is not to warn about the madness of today’s world by choosing to see only its grimace. I don’t think we’re all going to become fictosexuals (i.e., only feel desire for fictional characters) or therians (people who identify as non-human or not entirely human). Radical examples allow us to refine our exploration; they allow us to trace the perimeter of this territory, which often expresses itself in much more innocuous forms, even if they are dramatic for individuals, such as the ebb of desire.

Some of these groups, moreover, number in the millions: they are social phenomena that require our attention, or at least mine, since I am a sociologist. Take the shifters, or rather the shifterettes, as they tend to be girls: they practise “reality shifting”, a mental practice similar to lucid dreaming, through which some individuals claim to be able to project themselves mentally into imagined, alternative universes. The explosion of this practice since the early 2020s is a social phenomenon, which some experts link to the experience of lockdown during the Covid pandemic, but which is more generally part of the “assault on reality” that I describe in my book.

However, this assault takes many forms, which did not start with the pandemic. But these forms have one thing in common: a growing difficulty with otherness. Whether we project our ego everywhere in the universe, in the hyperbolic manner of the most radical transhumanists, or whether we want to absorb the entire universe into our own ego through the feelings we impose on others, what disappears? It is the other.

Among the many forms of this ‘assault on reality’, some are militant, even brutal, such as the suppression of data on climate change and the attacks on science carried out by the Trump administration. But aren’t others, such as these shifters, more akin to a desire, a disinterest in reality?

Desire seeks to impose itself on reality; this is the common thread running through all these phenomena. But this desire can ebb away. This is what Alain Ehrenberg pointed out in his book La Fatigue d’être soi (The Weariness of the Self, 1998). He showed that, in our societies, which have removed many of the prohibitions of the past, depression has replaced neurosis as the new malady of the century. Many psychiatrists agree that we are currently experiencing an epidemic of depression. However, depression is not so much about being unhappy as it is about the absence of desire and, incidentally, pleasure: anhedonia. This ebb in desire is at the heart of the experience of certain communities mentioned in my book, such as the hikikomoris, who appeared in Japan in the 1980s, young people – mostly boys in this case – who, faced with the pressure to succeed in the school system and confronted with the first major economic crisis Japan had experienced since the Second World War, gradually gave up leaving their bedrooms. These communities then spread under other names to other developed countries. What do these hikikomoris have in common? Their desire recedes to the point where they want to avoid reality and spend their entire lives in their own rooms.

This drift has an extraordinary advantage for those who abandon themselves to it: it allows them to control uncertainty. Hikikomoris have a way of ritualising their daily lives that makes them little domestic tyrants: they must eat at a certain time, etc. Their entire existence can be interpreted as a reduction of uncertainty. And what is uncertainty? It is the clear awareness of the openness of possible times. If you make tomorrow resemble today, which resembles yesterday, time becomes a line without a range of uncertainty and possibilities. life becomes an eternal present.