Innovation: calling on the expertise of people with disabilities as a way to co-create

- The law of 11th February 2005 introduced accessibility and anti-discrimination measures for people with disabilities in France.

- Twenty years on, to make accessibility for all a reality, people with disabilities must be involved in the design of solutions.

- This “co-creation” approach is based on the idea that user experience can enrich and guide the design of more appropriate solutions.

- It values “experiential knowledge”, defined as knowledge derived from individuals’ everyday experiences, as a valuable source of knowledge.

- This knowledge enables companies to develop inclusive products that are better suited to a diverse range of users, thereby strengthening their competitive advantage.

In 2025, the French law of 11th February 2005 will celebrate its 20th anniversary. This landmark law recognised the rights of people with disabilities and promoted a more inclusive society by imposing obligations in terms of accessibility and combating discrimination. It marked a major step forward by establishing the principle of “access for all” in both public spaces and the world of work. However, 20 years on, the expected societal transformation has only been partially achieved1 and the international context is even raising the risk of a backlash against the goal of a more inclusive society.

One of the foundations of the transformation demanded by people with disabilities and the organisations that represent them is participation. For “access for all” to become a reality, people with disabilities must be involved in the design of solutions. Too often, inclusive innovation is still designed by experts without the participation of those most affected. Yet social science and innovation management literature shows the importance of end-user participation in the creation process2. This approach, known as “co-creation” or “co-design”, is based on the idea that user experience can enrich and guide the design of more appropriate solutions. In the field of disability, this question is particularly crucial: how can truly effective solutions be designed without incorporating the knowledge gained from the lived experiences of those concerned?

The experience of disability: an expertise in its own right

Traditionally, expertise is associated with formal, academic knowledge, transmitted for example by health professionals or researchers. However, work in sociology and management sciences has shown that personal experience can also be a valuable source of knowledge3,4. This is known as “experiential knowledge”, defined as knowledge derived directly from individuals’ everyday experiences. This knowledge is often overlooked because it is considered subjective or because it is not expressed in as structured a way as formal knowledge.

However, the recognition of experiential knowledge has begun to transform practices in the fields of urban planning5 and mental health6. As illustrated by the recent referendum asking Parisians to decide whether or not to pedestrianise 500 streets, citizens are increasingly being asked to give their opinions on urban development. In the field of mental health, the rise of “peer support”, i.e. mutual aid between people suffering from the same mental illness or addictions, has led to the recognition of experiential knowledge, repositioning the patient in the care relationship. This is described by France Inter journalist Nicolas Demorand, who recently went public about his bipolar disorder, when he talks about “co-construction” to describe his care relationship with his psychiatrist7. Nevertheless, recognition of experiential knowledge remains uneven, oscillating between complementarity and opposition to professional knowledge.

Experiential knowledge differs from mere experience. It requires awareness or formalisation of the experience. Lehrer8 proposes a progressive approach to this formalisation: we are “familiar with” (acquired knowledge) before we “know how” (practical knowledge) and then “know that” (propositional knowledge). Other researchers have worked to describe the types of experiential knowledge acquired by individuals and shared, particularly in peer-to-peer sharing9.

In the field of innovation, companies have been integrating consumers’ experiential knowledge since the 1980s, particularly through co-design practices for products and services. Management science research shows that these practices improve customer satisfaction and offer a competitive advantage10. The selection of “good” consumers for co-design has attracted particular interest, particularly around “lead users” [editor’s note: individuals or organisations that anticipate the crucial needs of the general public in advance and develop solutions to meet these needs]. However, the knowledge they draw on remains poorly characterised, as is the case with so-called “ordinary” consumers.

In our research11, we started from the observation that the experience of pain and unsuitable environments faced by consumers with disabilities gives them a unique perspective that can be useful in the product design process, not only for themselves, but also in a universal design approach, i.e. for all consumers12 . For example, for many consumers, the physical experience is not a factor when it comes to consumption; we don’t notice it because it doesn’t create any constraints. For people with disabilities, however, it takes on a more central role, leading to a different and more conscious experience of use. Based on these findings, we sought to better characterise the experiential knowledge of consumers with disabilities.

Questioning all aspects of experiential knowledge

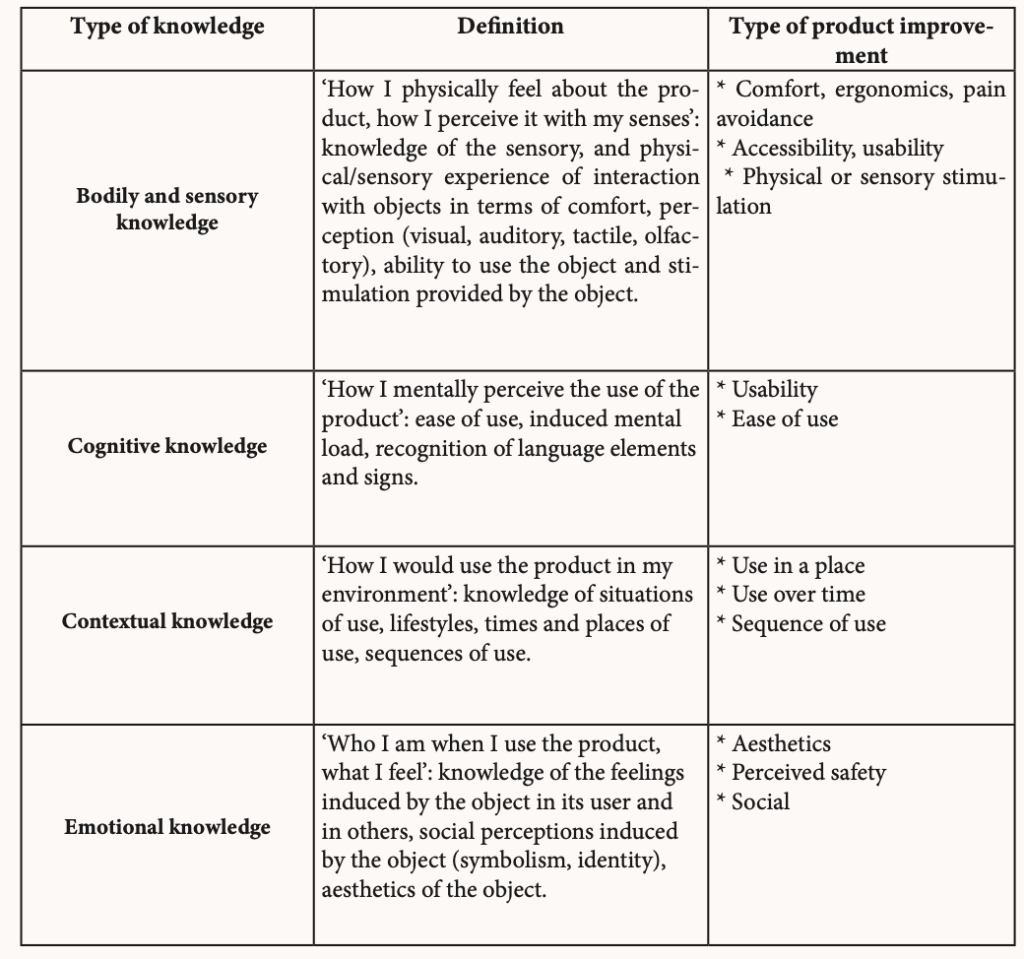

Since 2018, APF France handicap’s TechLab has been involving consumers with disabilities in the design of products and services for companies of all sizes that want to better meet their needs. Our research at the TechLab shows that experiential knowledge can be classified into four categories: physical and sensory knowledge, cognitive knowledge, contextual knowledge and emotional knowledge.

Each of these categories reveals how experiential knowledge enriches our understanding of the drivers of co-design with consumers and highlights the specific nature of the improvements they can bring.

Three principles for leveraging this knowledge

Our research has identified three characteristics of experiential knowledge that are useful for leveraging it.

- Recognise the multidimensional nature of knowledge, which makes different categories of knowledge interdependent.

- Consider its transferability: experiential knowledge can be transferred from one product to another and goes beyond the specific disability of the individual. Therefore, it is not necessary to be a user of a specific product to have a relevant opinion to express.

- Go beyond basic needs: As people with disabilities often face barriers that hinder basic needs such as mobility, they can be encouraged to explore the range of possibilities beyond immediate accessibility.

Towards more inclusive innovation and more effective co-design practices

Recognising consumers’ experiential knowledge as a legitimate form of expertise fundamentally transforms innovation processes, particularly when it comes to integrating the perspectives of traditionally marginalised populations. Organisations that adopt these participatory approaches are not only responding to an ethical imperative: they are developing products that are inherently more suited to a diverse range of users, thereby enhancing their competitive advantage. Two decades after the enactment of the 2005 law, integrating the experiential knowledge of people with disabilities into all design processes could be a key lever for a more inclusive society. This approach is now a strategic necessity for companies whose products and services will have to demonstrate accessibility from 28th June 2025, when the European Accessibility Act13 comes into force.

https://www.publicsenat.fr/actualites/societe/accessibilite-accompagnement-emploi-20-ans-apres-la-loi-handicap-le-senat-dresse-un-bilan-en-demi-teinte↑