How the Sun’s “seasons” affect our planet’s atmosphere

- The Sun has an impact on its immediate environment and on more distant planets, but also on the entire region of space surrounding our Solar System, which is called the heliosphere.

- There are various consequences of the interaction of this flow of solar particles with the Earth's magnetosphere; one of the most beautiful being the Northern Lights.

- A negative consequence of this permanent bombardment is it that it can prematurely age satellites and even lead to them failing because they are highly exposed to solar wind particles in orbit.

- The Sun's extremely high temperature allows for the formation of bubbles that 'burst' its atoms into a soup of nuclei and free electrons. This 'plasma' is very sensitive to electric and magnetic fields.

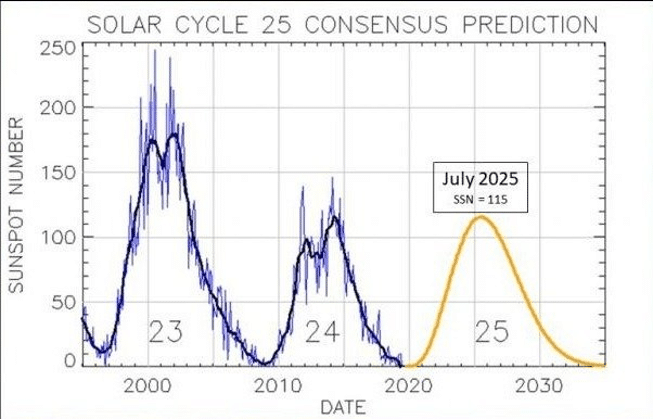

- Solar activity evolves periodically in a long cycle of about 11.5 years, passing through a maximum of activity and a minimum. These can be referred to as the Sun's 'seasons'.

Every 11.5 years, the Sun goes through a period of particularly intense activity. It is characterised by strong solar wind, leading to more frequent satellite failures due to a bombardment of particles from the Sun. But whether solar activity is high or low, life is tough for technologies in orbit. The Sun has an impact on its immediate environment, on the more distant planets, but also on the whole region of space surrounding our Solar System, which is called the heliosphere.

What are the consequences for space activities?

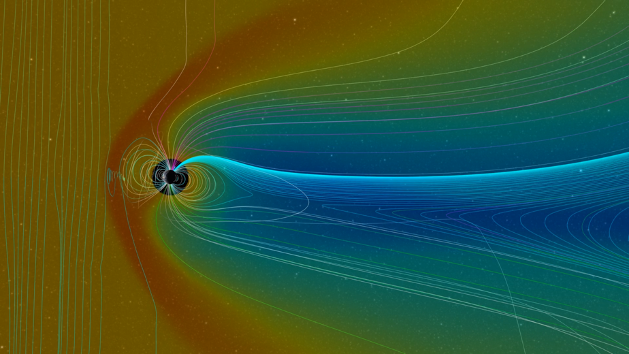

The consequences of the interaction of this flow of solar particles with the Earth’s magnetosphere – our planet’s magnetic field – are numerous and varied. One of the most beautiful is, of course, the auroras in the northern and southern hemispheres (aurora borealis and australis respectively). At the poles, a small fraction of the solar wind can cross the magnetosphere (see image of the Earth’s magnetic field below) and violently interact with the Earth’s atmosphere. This transfer of energy excites the rarefied atoms and molecules at the top of the atmosphere, which re-emits it in the form of magnificent drapes of light.

Other consequences are more problematic. Satellites in orbit around our planet are highly exposed to solar wind particles. This permanent bombardment is one of the main reasons for the ageing or possible failure of these satellites. Like the irradiation processes used in industry on Earth, the mechanical, electrical and/or optical properties of satellite components is gradually altered. Transient or permanent failures of the on-board electronics may also occur (more frequently, of course, during solar maximum periods). Therefore, they must often be shielded, and their electronics reinforced to better withstand solar radiation.

Ground technologies can also be affected by the solar cycle. While the Sun’s temperature and light intensity do not change during the solar cycle (it does not get hotter every 11.5 years), the geomagnetic storms caused by a coronal mass ejection entering the Earth’s environment can be so intense that huge induced electrical currents appear in the Earth’s power grid. In 1989, for example, a widespread power failure brought Canada to a standstill for nine hours. The entire network collapsed in just 25 seconds. This is problematic as our civilisation is becoming ever more dependent on electricity…

The Sun makes bubbles

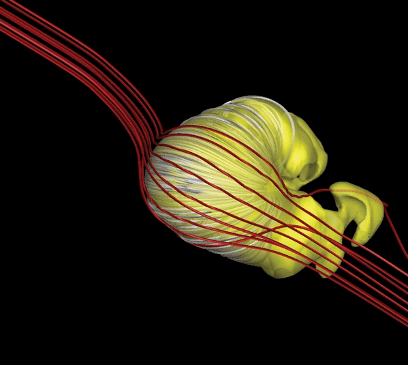

Astronomers have long sought to characterise the so-called heliosphere, which limits two zones of space: the interior, dominated by the solar wind, and the exterior, made up of particles in the interstellar medium. Since the Sun emits solar wind particles in a globally isotropic manner, its shape was initially imagined as an elongated « bubble » surrounding the solar system. However, a recent paper1 suggests, based on extensive numerical simulations and sky observations, that the heliosphere of our Solar System is shaped like… a croissant! This is due to the complex interactions between the hydrogen atoms in the interstellar medium and the charged particles emitted by the Sun.

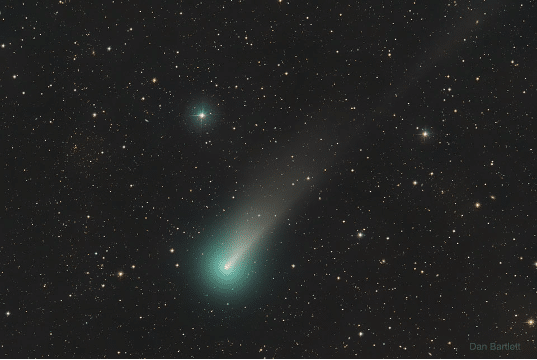

The shape of this heliosphere will obviously depend on the composition, density, and speed of the flow of particles coming from the Sun. Every second, the Sun loses about 1 million tonnes of electrons, hydrogen nuclei and helium in a ‘wind’ that spreads around it, bathing the planets and other bodies as far as the edges of the Solar System. It is, for example, this solar wind that shapes one of the two types of tails of comets by carrying the dust and gas particles ejected from the comets’ nuclei away from the Sun.

This solar wind also interacts with the planets of the Solar System, more or less directly, depending on the presence or absence of a magnetic field around them. The very high temperature of the Sun ‘explodes’ its atoms into a soup of nuclei and free electrons, called a ‘plasma’, which is very sensitive to electric and magnetic fields. So, when these particles arrive near Earth, its magnetic field will divert a significant portion of them and deflect the particle shower before it can irradiate and sterilise the Earth’s surface.

Solar cycles and space weather

What are the properties of the Sun’s ‘wind’ of particles? Is the wind constant? Regular? Or do ‘solar wind storms’ exist? Also, are there, as on Earth, ‘seasons’ when the solar wind is more intense? The answer to both of these questions is yes.

Just as the seasons on Earth reappear regularly each year, solar activity (which includes all the phenomena that occur on the surface of the Sun and around it) also evolves periodically in a long cycle of about 11.5 years.

During this cycle, the Sun goes through a maximum of activity (the solar wind will be on average denser and faster) and a minimum. This variation in activity is not limited to the amount of solar wind particles, however. The Sun also regularly produces eruptive phenomena called coronal mass ejections. These very intense bursts of solar particles are produced in very local regions on the surface of our star and are also ejected radially, at great distances from the Sun.

When the Earth finds itself in this direction, a particularly dense ‘wave’ of particles arrives two to three days after the start of the ejection. This wave of particles joins the classic solar wind for several hours. It is obviously during the years of maximum solar activity that the probability of these powerful eruptive phenomena producing ‘geomagnetic storms’ in the Earth’s environment is greatest.

It would be wrong, however, to think that space activities are quieter during solar minimum periods. The solar wind is less dense and there are fewer solar flares, but other phenomena take centre stage. For example, the Earth’s atmosphere also varies according to the ‘pressure’ of the solar wind. At solar minimum, the pressure is lower and the atmosphere extends further into space. This puts aerodynamic stresses on low-orbiting satellites and significantly reduces their life span.

To conclude, our star significantly influences the Earth’s environment. Its plasma fingers caress us night and day, and it is through understanding the complex interactions between the Sun and the Earth that humanity will be able to continue to understand space.