Space powers: how critical technologies are emerging from public-private partnerships

- In 1967, the Outer Space Treaty signed by the major powers affirmed that space is a common heritage of mankind, and then, in 1979, the Moon Agreement stipulated that there would be no ownership of resources.

- However, the example of NASA's Artemis programme shows that this framework is being reinterpreted and expanded as commercial space activities develop.

- The growth of the space economy relies on competition in critical and emerging technologies (CET), such as AI, semiconductors, quantum computing, cloud services, drones, etc.

- Above all, technological leadership depends on investment in human capital.

- Three major challenges shape the space sector: rethinking training, attracting capital to a high-risk sector, and enabling access to infrastructure through cross-sector partnerships.

The space economy is undergoing a fundamental transformation. In July 2021, private space flights by Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos demonstrated the growing commercial viability of space travel. That same year, China’s Zhurong rover joined NASA’s Perseverance on Mars, reflecting increased international participation in space exploration. These developments signal a broader shift in how governments and private enterprises approach space, with analysts projecting the space economy could reach $1.8 trillion by 2035.

This projected growth encompasses diverse activities ranging from satellite deployment and navigation systems to space tourism and planetary exploration. NASA’s planned 2028 Dragonfly mission, which will send a quadcopter-like rover to Saturn’s moon Titan using technologies demonstrated by Mars’ Ingenuity helicopter, exemplifies how public agencies and private companies are increasingly collaborating to advance space capabilities. SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy already having been booked for the launch.

Evolving Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

The legal foundation for space activities was established through the UN’s 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which designated space as a commons for all mankind, and the 1979 Moon Agreement, which prohibited resource ownership. However, these frameworks are being reinterpreted and supplemented as commercial space activity expands. The 2020 U.S. Artemis Accords represent one such evolution, creating non-binding multilateral arrangements for space cooperation. By July 2025, 56 countries had signed these accords. Meanwhile, national space programs have proliferated globally, with the European Commission’s June 2025 EU Space Act explicitly targeting leadership in the space economy. These policy initiatives have coincided with technological advances, particularly in AI and robotics, that have reduced space flight costs and accelerated innovation.

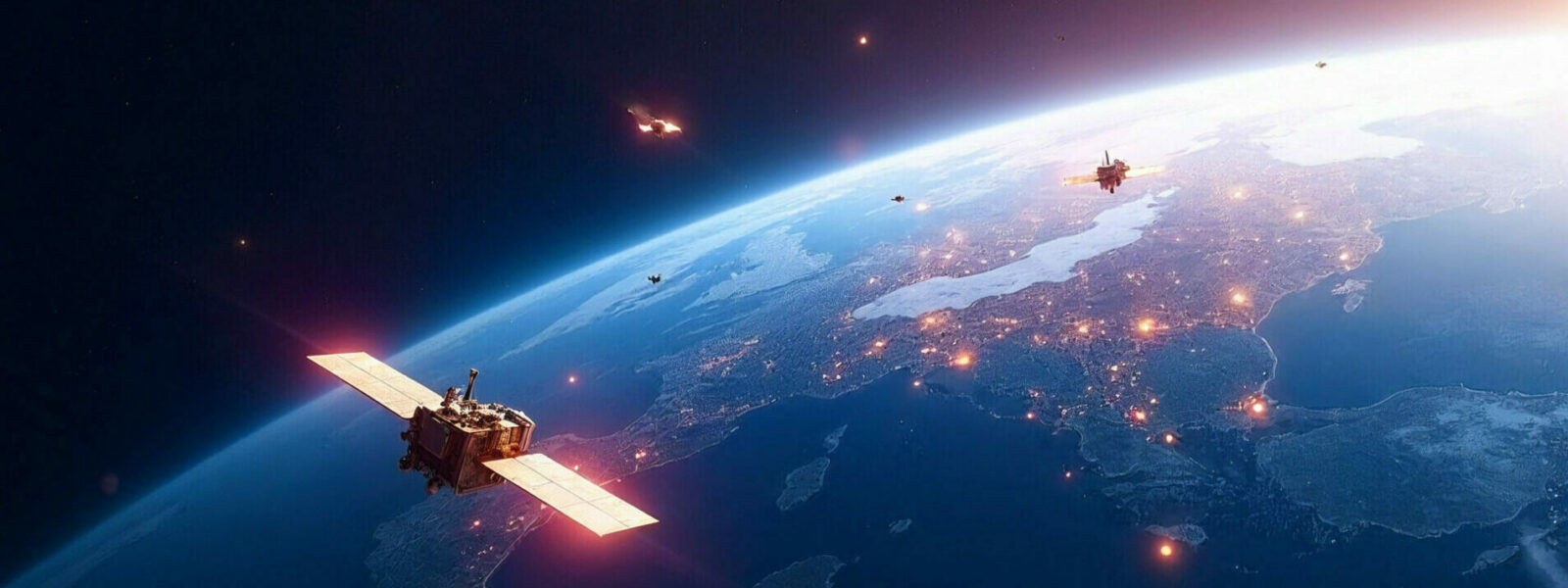

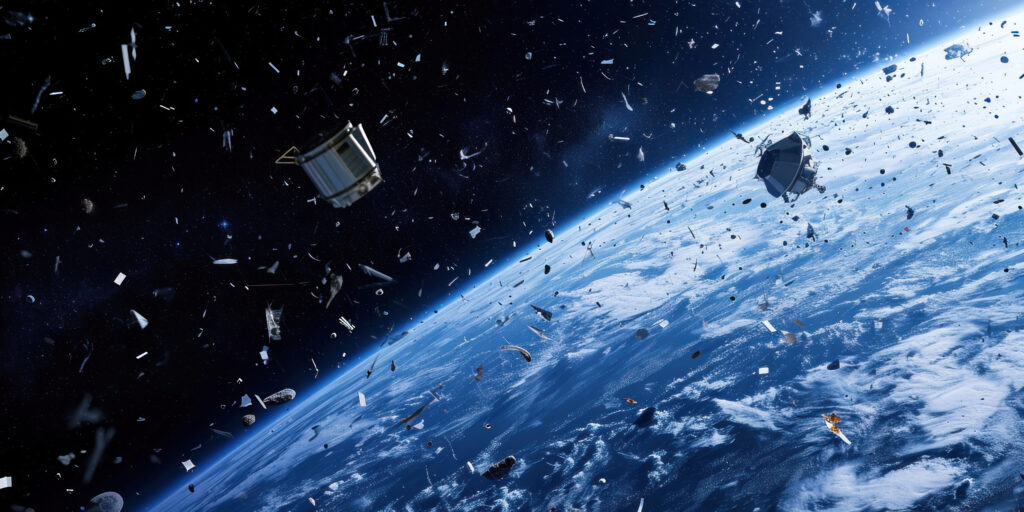

Commercial interests have also shaped the regulatory environment. The United States legislated space resource extraction for its citizens in 2015, with Luxembourg, the UAE, and Japan enacting similar provisions. More recently, August 2025 White House executive orders emphasised U.S. commercial space leadership. This policy direction reflects expectations that the space economy will deliver satellite internet, enhanced navigation, low Earth orbit commerce, space tourism, in-space manufacturing, asteroid mining, and potential settlements beyond Earth. These opportunities, however, coexist with significant challenges. Space debris in low Earth orbit poses growing risks to satellites and missions. While the U.S., Russia, and China are responsible for most orbital debris, regulatory frameworks remain underdeveloped. The absence of accepted definitions distinguishing debris from functional objects complicates risk assessment and investment decisions, creating uncertainty that could constrain future growth.

The Strategic Role of Critical and Emerging Technologies

Underlying the space economy’s expansion is a broader competition for leadership in Critical and Emerging Technologies (CETs). These technologies, often dual-purpose (civilian/economy and defence), include AI, advanced semiconductors, quantum computing, cloud services, drones, GPS, satellites, and advanced manufacturing and materials. The ‘critical’ aspect referring essentially to emerging technologies with the capacity to generate breakthroughs in key areas of national interests. CETs are characterised by their novelty, complexity, and resource requirements. They also rely on a supply chain of highly-trained professionals from diverse fields of knowledge able to collaborate globally and seamlessly and across multiple sectors.

CETs are central to Knowledge and Technology Intensive (KTI) industries, which contributed over $9tn globally in 2022, representing 11% of global GDP. Five economies—the United States, China, the EU-27, Japan, and South Korea—accounted for 80% of global KTI value, highlighting the concentration of technological capability. This concentration has prompted major policy initiatives aimed at securing or expanding technological leadership.

The EU is proposing a European competitiveness fund to support AI, semiconductors, robotics, quantum computing, space, and biotechnologies.

In the United States, the 2020 Trump administration National Strategy identified 20 Critical and Emerging technologies essential for defence and economic competitiveness, including advanced computing, AI, biotechnologies, quantum information science, and space technologies. The 2022 CHIPS and Science Act followed with $280bn in commitments over ten years to strengthen semiconductor supply chains and establish the NSF’s Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships. A March 2025 presidential executive order further tasked the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy with securing U.S. leadership through private sector investment and new research funding approaches emphasising the ‘business’ of discovery.

Other major economies have pursued parallel strategies. The EU’s 2025 Competitiveness Compass proposes a European Competitiveness Fund supporting AI, semiconductors, robotics, quantum computing, space, cleantech, and biotech. Japan’s Society 5.0 vision emphasises AI, robotics, quantum technology, and semiconductors. China’s Made in China 2025 targets manufacturing transformation, leveraging its extensive skilled workforce and dominance globally in rare earth production, which is essential for electronics and defence systems.

Deep Tech and the Innovation Pipeline

The translation of scientific advances into commercial applications increasingly occurs through deep tech enterprises—companies leveraging breakthroughs in science and engineering to address challenges in energy, food security, space exploration, and disease treatment. These ventures face distinct challenges: intensive early-stage R&D requirements, substantial capital needs before commercialisation, dedicated infrastructure demands, and dependence on specialised talent in fields like optical quantum systems engineering.

Deep tech sectors overlap significantly with CETs, encompassing AI, biotech, quantum computing, space technology, and defence technology. Recognising this connection, the European Institute of Innovation and Technology’s Deep Tech Talent Initiative aims to train one million people across 15 deep tech areas by 2025. Nearly one-third of European venture capital now flows to deep tech investments. Similarly, the U.S. government has been a major deep tech investor, though 2025 budget cuts to agencies like the NSF have raised concerns about sustained support. China has taken a strategic approach through a $138bn government-backed fund targeting quantum computing and space technology.

The 2024 Nature Index ranking of science cities highlights that half of the world’s top 20 science cities are now located in China.

The competition for technological leadership ultimately depends on human capital. China currently graduates significantly more STEM students annually than the U.S., Europe, and Japan combined, with over 40% of Chinese university degrees in STEM fields compared to 20% in the U.S. The 2024 Nature Index Science Cities ranking reinforced this shift, showing that half of the world’s top 20 science cities are now in China. The United States has historically compensated for domestic STEM production through international talent recruitment, particularly from China and India. However, this advantage is being challenged by policy changes. Budget uncertainties and grant cancellations have contributed to researcher departures from U.S. institutions. The September 2025 presidential proclamation imposing $100,000 fees for new H‑1B visa applications has particularly affected the technology sector, potentially accelerating talent flows to competing nations.

Case Study: Regional Innovation Ecosystems

While much attention focuses on major technology hubs, regional innovation ecosystems also play important roles in advancing space and Critical and Emerging technologies. New Mexico provides a useful example of how states can support technology development through infrastructure investment and research institutions. State-owned Spaceport America offers rocket testing facilities used by companies including SpaceX, providing access to specialised infrastructure that would require substantial private investment to replicate. At New Mexico Tech, researchers are applying biomimicry principles to develop drone technologies with applications ranging from planetary exploration to wildlife monitoring and aviation safety.

One project examines how monarch butterfly coloration contributes to energy conservation during their 3,000-mile migration, with findings that could inform aviation efficiency improvements. Another initiative is developing milligram-scale flying sensors inspired by dandelion seeds for Mars exploration. These sensors use piezoelectric materials to harvest solar and atmospheric energy, enabling autonomous operation in Martian lava tubes without batteries. Additional research includes nature-friendly surveillance drones using preserved taxidermy that blend with wildlife populations, providing insights into bird flight physics and flocking behaviours applicable to commercial aviation. These findings inform the development of predator bird drones designed to reduce costly bird strikes at airports. The New Mexico Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge provides an ideal observatory for this research.

Beyond research output, New Mexico Tech is developing as a regional drone technology hub through workforce development initiatives. A K‑12 drone program enables high school students to design and build drones during summer sessions, while approximately 40 graduate students from diverse disciplines have participated in drone technology, biomimicry, and planetary exploration research.

Many of these students have been awarded prestigious prizes for their contributions and these are frequently celebrated on social media. These students bond early as a team and are visible presenters at major conferences such as the 2025 AIAA Aviation and ASCEND Conference, sharing their work on drones and aerospace systems. Important local/regional community outreach generating excitement about how NMT is revolutionising drone technology is also achieved on an ongoing basis through a number of public outlets, including media interviews with e.g., New Mexico Frontiers Digital Show KRQE.

A drone major is currently being designed to connect community colleges across New Mexico to create a pathway for a future generation of students to actively contribute as part of the workforce designed for the State’s aerospace industry. As part of the core facilities available there is also a netted drone cage where any types of drones can be tested without having to worry about breaching the FAA rules.

Challenges and Opportunities

With growing demand from governments throughout the world for more ‘bang for buck’ from their scientific research investments, strategic targeting of CETs will likely intensify, with increased expectations for breakthrough results. However, realising the potential of these technologies requires addressing several interconnected challenges. First, developing interdisciplinary high-tech talent requires rethinking education and training approaches to foster collaboration across traditional disciplinary boundaries. Second, attracting investment capital that accepts high technical risk and extended development timelines remains difficult within conventional funding structures. Third, securing infrastructure access depends on cross-sector partnerships between government, academia, and industry; relationships that require sustained commitment and alignment of incentives.

The New Mexico Tech example illustrates how these challenges can be addressed through coordinated approaches combining research facilities, cross-sector partnerships, and multi-level talent development. By connecting scientific achievement with practical applications, such ecosystems can inform public-private investment decisions and accelerate technology commercialisation. Success in the emerging space economy and related technology sectors will ultimately depend on how effectively nations and regions address these fundamental challenges while fostering innovation across public and private domains. The continued expansion of space activities, combined with advances in Critical and Emerging technologies, suggests that the coming decades will see significant developments in how humanity accesses and uses space—developments that will be shaped as much by policy choices and institutional arrangements as by technological capabilities.

Dr Hassanalian acknowledges the support of: the US NSF; New Mexico Space Grant; NASA; Alpha Foundation; NIOSH-CDC; New Mexico CONSORTIUM; and SciVista.