The largest digital camera ever built will shed new light on the universe

- After 20 years of development, the LSST camera has been finalised.

- Thanks to the technology and the expertise of various laboratories, it will be able to observe the universe in unprecedented detail.

- The 3,200-megapixel camera will offer a new understanding of the universe by studying dark matter and dark energy.

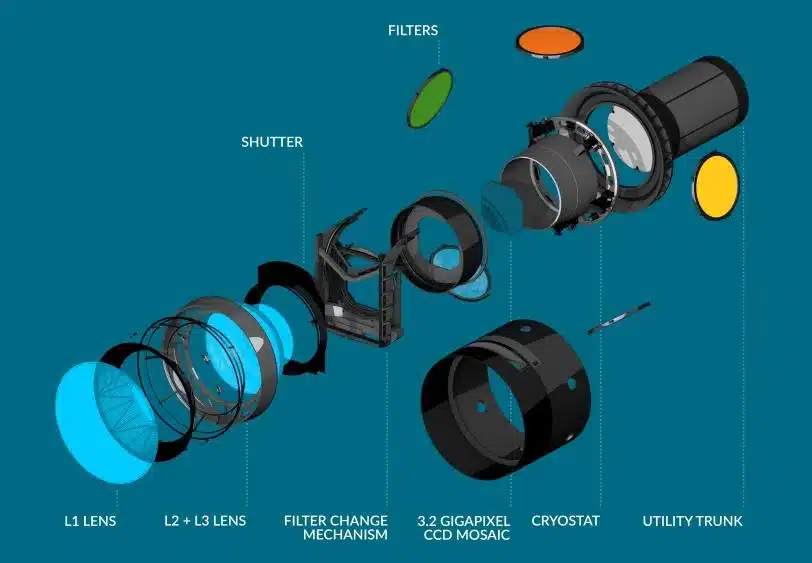

- The efficiency of LSST is guaranteed by the innovative technologies that make it up: six filters, filter changer, fast readout electronics, CCD detectors, etc.

- Optimisation of the readout electronics will enable the camera to process data efficiently, paving the way for major discoveries in astronomy.

- While certain aspects are still in the commissioning phase, the first images are expected in spring 2025.

After more than 20 years’ work, the LSST (Legacy Survey of Space and Time) camera is now complete and ready to be installed on its telescope at an altitude of 2,700 meters on the Cerro Pachón mountain in the Chilean Andes, one of the best astronomical sites in the world and already home to numerous instruments such as the VLT1 and ALMA2.

The 3200-megapixel camera will be capable of scanning the entire sky in just three days, taking 800 images per night, each covering an area 40 times the size of the Moon. It will thus be able to observe the universe in unprecedented detail, but not only: it will also help to advance our understanding of dark energy – responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe. To do this, it will look for signs of what is known as the weak gravitational lensing effect, in which very massive clusters of galaxies subtly bend the trajectories of light from background galaxies before it reaches us. This process reveals important information about how mass has been distributed in the universe over time.

The camera will also look for dark matter, the mysterious substance thought to make up 85% of all matter in the universe by observing the distribution patterns of galaxies and how they evolved over time.

The camera was developed and built by researchers and engineers at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in the US. The partner laboratories that contributed to the project are: Brookhaven National Laboratory in the United States, which built the camera’s digital sensor array; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, also in the US, which built the camera’s lenses; and National Institute of Nuclear and Particle Physics (IN2P3/CNRS)in France, which participated in the design of the sensors and electronics, and built the camera’s filter changer system. This system will enable the camera to take images in six distinct bands of light, from the ultraviolet to the infrared.

“The camera is about the size of a car,” explains Johan Bregeon from the Subatomic Physics and Cosmology Laboratory (LPSC)3 at IN2P3/CNRS, who has been working on the project since 2019. It weighs around 3,000 kg and has three lenses. The front lens measures almost 160 cm, which is thought to be the largest high-performance optical lens ever made.

A truly revolutionary camera

“The LSST camera is truly revolutionary and will do more than just take pretty pictures. It is an instrument capable of detecting light and processing it as faithfully as possible.”

The three-lens system allows the field of view to be corrected so that a larger portion of the sky can be observed without making the camera bigger. At the focal plane of these lenses are the CCD detectors, which are the components that collect the light. Another important part of the instrument is the filter changer.

“To do astronomy, and cosmology in particular, we need to observe the sky in several optical bands (or wavelengths) down to the near-infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum. To do this, we use filters, that is, pieces of glass that allow a certain band of frequencies to pass through.”

Six filters and a complex mechanical system

IN2P3/CNRS contributed to the filter changer system, which consists of a carousel containing six filters and a complex mechanical system, enabling them to be changed in less than two minutes. “The filters are 75 cm diameter discs. The lightest weighs 25 kg and the heaviest 38 kg, and we have to be able to position them with a precision of a few hundred microns. What’s also important to understand is that a filter will be changed very regularly during the observations, several times a night. So, over the 10 years that the telescope is expected to operated, the filter changer will typically have to operate over a hundred thousand cycles. From a mechanical point of view, this is difficult to implement because we obviously had to take into account wear problems.”

Associated with these filters is the filter loading system. “This system allows us to take a filter from a box and insert it into the carousel of the filtration chamber after removing the existing filter. This loader was essentially designed, tested, built and validated by the teams at the LPSC in Grenoble, where I work.”

Fast readout of CCD detector data

The challenge was not only to build the world’s largest digital camera for astronomy, but also to be able to quickly read out the data from the CCD detectors. Currently, for existing cameras that operate in more or less the same way, reading a few hundred million pixels takes around 30 seconds. “For the LSST, we wanted to be able to make more than 1,500 exposures per night, so 30 seconds was too long.”

As a result, there was much optimisation and design work on the readout electronics to ensure that they were efficient and able to read the 3 billion pixels in around just two seconds.

“As well as improving the readout electronics, we also had to learn a lot about how the CCD detectors work, to make sure that once the raw data has been output by the camera, the images produced are as faithful as possible to the portion of the sky we are observing.”

Several laboratories are working on the calibration and reduction of the raw images to obtain the best possible images. This part of the camera is still in the commissioning phase. “I’m currently analysing some of the data we took last year when the camera was at SLAC for its test runs. We have obtained data that will allow me to check the alignment of the lenses with the focal plane of the camera.” The first images are expected in spring 2025.

Interview by Isabelle Dumé

Références:

Aaron J. Roodman at al. Integration and verification testing of the LSST camera. SPIE Astronomical Telescopes + Instrumentation 2018, Jun 2018, Austin, United States. pp.107050D, 10.1117/12.2314017. https://hal.science/hal-01880806

Pierre Antilogus et al. Design, assembly and validation of the Filter Exchange System of LSSTCam. In SPIE Astronomical Telescopes + Instrumentation 2022, volume 12182, page 121823A, Montréal, Canada, July 2022. doi: 10.1117/12.2629336. https://hal.science/hal-03838583