3D printing technology, which has been around for nearly 35 years, has played a major role in reinventing traditional manufacturing models. It has enabled the creation of a market estimated at €30 billion euros with a growth rate of 20% per year. However, when an invention reaches maturity, there comes a time when a new technology arrives on the market that will replace it. 4D printing, where the fourth dimension is time, represents this breakthrough technology.

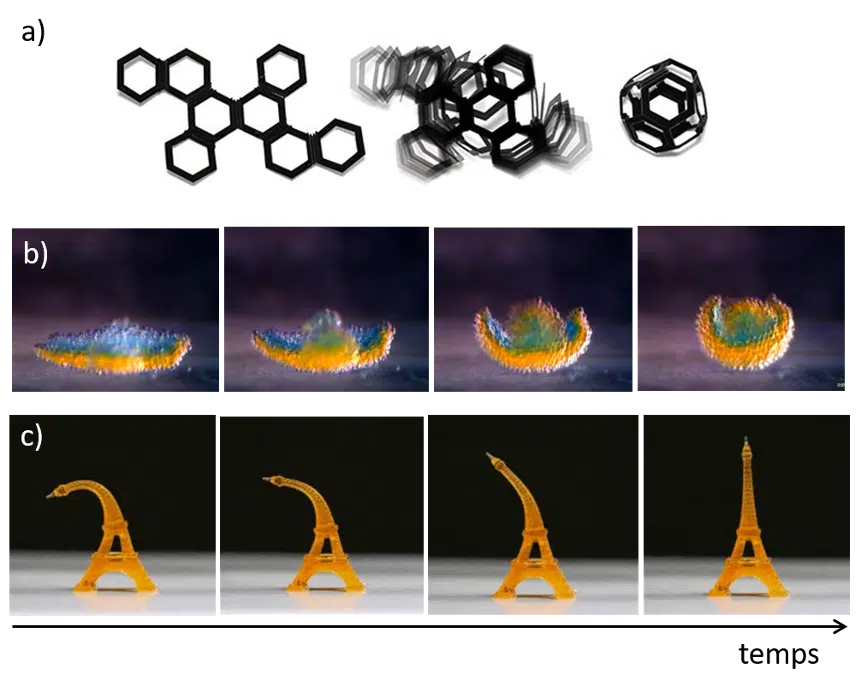

In a way, 4D printing represents a functional form of 3D printing and allows the printing of dynamic objects that actively respond to external stimuli. This possibility of programming the material so that artificial objects can behave like intelligent organisms opens new perspectives for research alongside an infinite number of potential applications.

Time, the 4th dimension

Paradoxically, the fascinating hypothesis of being able to program matter has previously been introduced in another scientific field. In 1991, Toffoli and Margolus, two computer scientists from MIT, introduced the term “programmable matter” to describe a set of computational nodes arranged in a certain space, which can communicate with each other only via first neighbours1.

This idea, by cross-fertilisation, spread to other disciplines, until in 2005 the DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) launched a multi-year project with the entitled “Realizing Programmable Matter”, focusing on modular robotics, programming assemblies and nanomaterials2. Now, the story crosses paths with that of intelligent materials; meaning materials with properties that can be activated or modified by external stimuli either physical (electric field, magnetic field, light, temperature, vibrations), chemical (PH, photochemistry) or biological (glucose, enzymes, biomolecules).

Finally, in 2013, Skylar Tibbits, founder of the Self-assembly lab at MIT, during his speech at a TedX conference, proposed using smart materials in 3D printing processes to produce programmable objects, and proposed the name “4D printing” for this new technology. The convergence of these three areas of research – 3D printing, programmable materials and smart materials – led to the 4D revolution3.

More complicated than it sounds

Clearly, at the heart of this new technology are smart materials. This is both the greatest asset and the biggest hurdle to its development, as research in this area is still in its infancy and few smart, printable materials are currently available (mostly polymers). This is why part of the research is focused on the possibility of extending the set of printable materials to ceramic and metallic materials, but also to biological and composite materials.

However, the material is not the only criterion to consider, it is also necessary to be able to design and create an object with a desired behaviour. Hence, such operations require work to correctly combine material, processes, and functionalities. As well as develop methodology based on the triad of design-modelling-simulation so that the printed object responds in an appropriate way to external stimuli.

In parallel with computer science, if a “bit” is the basic unit of programming, the voxel (a contraction of the words volume and element) is the elementary volume that stores the physical/chemical/biological information of an active material in 4D printing. Programming an object with printed behaviour in 4D therefore means modelling and simulating the optimal distribution of voxels so that the application of a stimulus corresponds to a deterministic effect. This complex problem requires ad hoc solutions where the desired behaviour is treated as an input variable, while the action (the voxel distribution) is treated as an output variable.

Finally, an object printed in 4D can be heterogeneous. That is to say: composed of one or more active materials interspersed with passive elements. This requires the development of multi-material printers and specific codes to adapt them to the materials used and the stimuli introduced.

What are the applications?

The possibility of combining complex geometries and evolving behaviours allows 4D printing to push the limits of object design and to revolutionise the world of manufacturing as it is understood today. It will foster the development of new technologies that are based, for example, on self-assembly, if the printed elements can assemble themselves autonomously at a specific time and place without human intervention. On self-adaptability if the printed structures can combine sensing and actuation within the same material. Or on self-repair, if printed objects possess the ability to detect and repair defects (wear, manufacturing) by themselves reducing the need for invasive procedures.

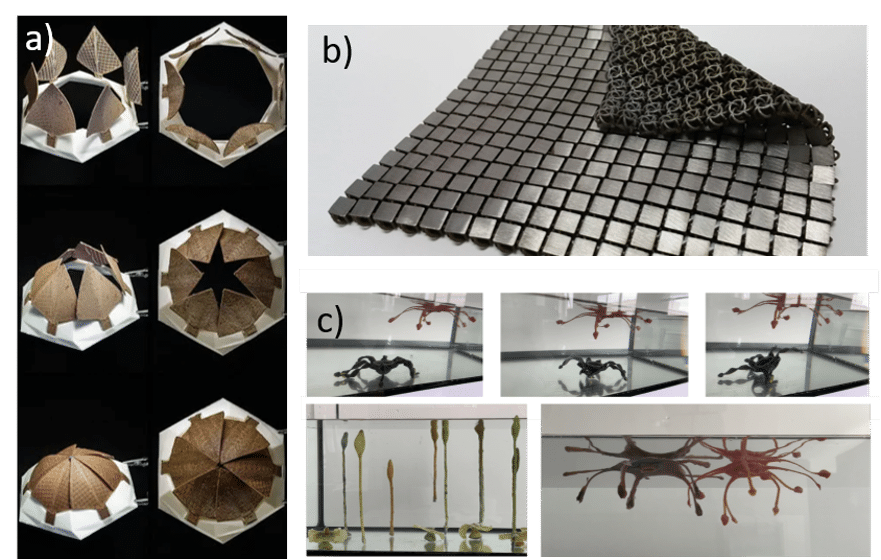

There are countless possibilities. 4D printing is already a driving force in flexible robotics for the fabrication of ever smaller robots (milli-robots, micro-robots, nano-robots) capable of working in hazardous environments or moving in confined environments, such as in the human body, to deliver a drug or to perform micro-invasive operations. In the field of biomedical applications, studies are underway to be able to bio-print stents, organs, and intelligent tissues. 4D printing will promote the development of flexible and embedded electronics as well as intelligent sensors adapted to the connected city.

In the field of energy, research is underway to maximize the efficiency of solar cells by integrating microstructures printed on flexible substrates. We can imagine consumer applications in the field of fashion and lifestyle, such as self-adapting biomimetic textiles or intelligent self-folding shoes. In architecture, 4D printing will allow the development of a new approach focused on sustainable development such as the Hygroskin project, which uses the hygrometric properties of wood to close and open a pavilion according to the humidity without any intervention or external energy. 4D printing also finds applications in research and creation practices in art and science around the notion of matter with behaviour to question the relationship between the living world and the artificial world.

The future of 4D printing

To quote Bernard de Chartres “we are like dwarfs on the shoulders of giants”. We can already affirm that 4D printing has been added to the process of profound transformation, of design and production of industrial objects, initiated by additive manufacturing. Although compared to the global market for 3D technology (€30bn/year), the market for 4D printing is still modest (€30–50m/year), its disruptive character is obvious. This is not surprising because in the life cycle of a product, 4D printing is still in its infancy. For this reason, and beyond the technical-scientific developments, 4D printing still needs to find its economic model and demonstrate the possibility of industrial production at an economic cost. Finally, in order for 4D printing to leave the research laboratories, this technology must necessarily go through the implementation of a clear and ambitious roadmap and create in parallel a “social desirability”. This will also require the willingness of investors and industrialists to support 4D printing and to push it towards economic maturity.