The phenomenon of laser filamentation occurs during the propagation of intense laser pulses of femtosecond duration. It can be exploited for many applications: revolutionary improvements in optical remote sensing for atmospheric science; supersonic laser booms to reduce the pressure of the shock wave at the front of an aircraft travelling through the atmosphere at supersonic speed; laser lightning rods to protect against lightning; or virtual plasma antennas for radio wave emission.

High peak power laser beams induce several important non-linear effects that occur as they propagate through the air. These effects cause some of the beam energy to spontaneously self-focus so that it concentrates to form intense channels of light called filaments – bands of light a few microns wide and up to several metres long. This self-focusing occurs at laser powers above a certain threshold and increases the intensity of the beam to the point where atoms in the atmosphere are ionised, generating a plasma. Filaments are typically produced when the laser beam has a peak power of more than 5 gigawatts (GW). In simple terms, laser filamentation is a special laser propagation regime obtained when very intense beams have a duration of only a few hundred femtoseconds (10-15 s).

If the beam contains only a few millijoules of energy, all its power will be self-focused into a narrow beam and produce a single filament. However, small variations in cross-sectional intensity, together with air turbulence, make beams of a few centimetres in diameter and of energies on the order of joules to self-focus into multiple filaments. The result is many filaments – up to 1,000 – distributed more or less randomly over the cross-section of the beam.

These filaments can be used for a variety of applications – to guide and control electrical discharges, for example, since they create a preferential path for these discharges. They can be channelled over a distance of up to five metres in a straight line.

Virtual plasma antennas and laser light bars

These discharges could be used to make a type of antenna that exploits the conductive properties of straight discharges for transmission in the radiofrequency domain. The idea here is to replace metallic conductors, which are quite big, with plasma conductors produced with these femtosecond filaments.

The other important application is the laser lightning rod. This device is similar to the virtual plasma antenna but extends over several hundred metres. The idea is to make a very long filament capable of guiding lightning and possibly triggering it before the storm cloud arrives near a sensitive site, such as an airport. This technique could help protect these sensitive targets by diverting the lightning to a capture point. We are working on this subject in our laboratory as part of the European “Laser Lightning Rod”.

We are trying to demonstrate this “lightning guidance” under real conditions – in the Swiss mountains. We have identified a site here where lightning is very frequent and always occurs in the same place, which is ideal for experiments. This would allow us to have more possible lightning events near our laser and to see if our technique works with real lightning.

A supersonic laser boom

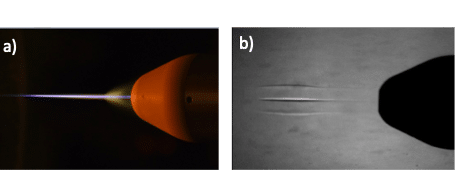

When we make the filaments – and our plasma – we heat the air, ionise the atoms and deliver laser energy locally. This heating occurs in a very uniform line thanks to the filamentation process. We have recently demonstrated, using a scale model aircraft in a wind tunnel, that such filamentation heating at the front of an aircraft travelling at supersonic speeds (Mach‑3) forms a bubble that deforms the shock wave on the nose of the aircraft. This reduces its drag by 20–50%. This heating also reduces the energy needed to move the aircraft forward, thus improving its fuel consumption.

We are working to develop this concept to find out if a long laser deposit generated at a higher rate can reduce the drag of the aircraft continuously and if it can be used to control its direction.

There are also several applications related to the fact that filaments can produce intense light with a very broad spectrum at distances of up to one kilometre. This can be interesting, for example, for a multi-frequency LiDAR (light detection and ranging) system because many light frequencies are generated in the filament. These frequencies are scattered by the air particles over a distance of 1km and can be used to analyse the composition of the air.

In the context of LiDAR and optical remote sensing, the plasma we create in the filament can emit coherent radiation and act naturally as a UV laser source. Molecules that are ionised or excited in the plasma can amplify a photon emission very strongly and the elongated shape of the filament makes this gain very directional. If the intensity is high enough, one can excite the nitrogen molecules in the air and so obtain a relatively intense directional and coherent ultraviolet emission. So far, we have demonstrated that this effect works well in the laboratory and we are working to improve its effectiveness at greater distances in air at atmospheric pressure.

Références :

- T. Produit, P. Walch, C. Herkommer, A. Mostajabi, M. Moret, U. Andral, A. Sunjerga, M. Azadifar, Y.-B. André, B. Mahieu, W. Haas, B. Esmiller, G. Fournier, P. Krötz, T. Metzger, K. Michel, A. Mysyrowicz, M. Rubinstein, F. Rachidi, J. Kasparian, J.-P. Wolf, A. Houard, The Laser Lightning Rod project, The European Physical Journal Applied Physics 93, 10504 (2021)

- P.-Q. Elias, N. Severac, J.-M. Luyssen, Y.-B. André, I. Doudet, B. Wattellier, J.-P. Tobeli, S. Albert, B. Mahieu, R. Bur, A. Mysyrowicz and A. Houard, Improving supersonic flights with femtosecond laser filamentation, Science Advances 4, eaau5239 (2018)

- A. Houard and A. Mysyrowicz, Femtosecond laser filamentation and applications, Light Filaments: Structures, challenges and applications, Institution of Engineering and Technology, pp.11–30 (2021)