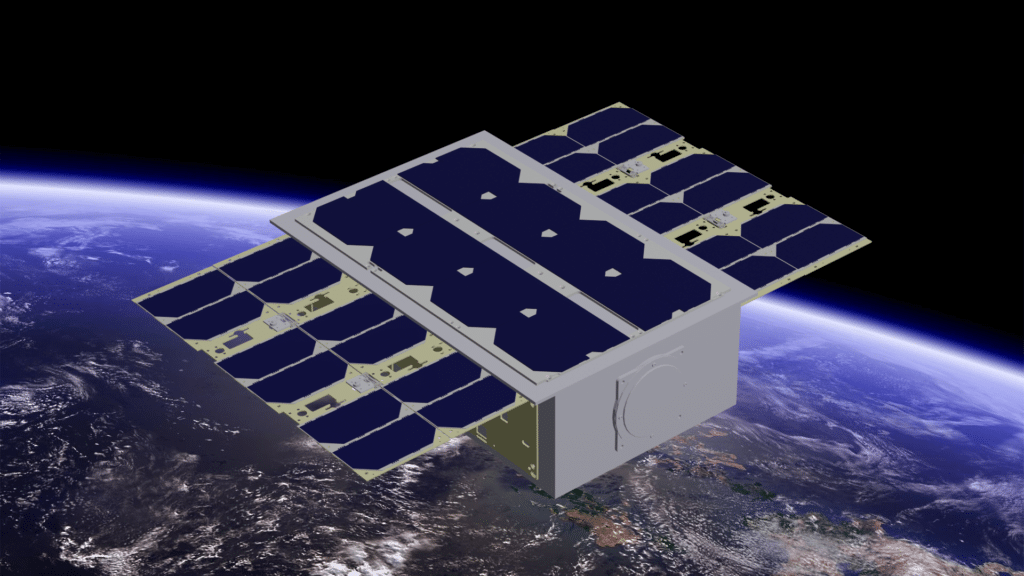

Space, hitherto an area restricted to a few governmental agencies, is now accessible to a wide range of people. As such, satellites have benefited from the miniaturisation of electronics to shrink to the size of “nanosatellites”. Even if this category is not clearly defined, it generally designates small-sized satellites: between 1 and 25 kg, while “minisatellites” weigh between 100 and 500 kg and a standard telecommunications satellite weighs nearly 6,000 kg.

Their small size, low cost and the rise of an ecosystem of suppliers have granted students, scientists, or private companies, an easier access to space. From 1998 to 2012, only 136 nanosatellites were launched. In the past seven years, this figure has been multiplied by 10 and has reached a total of 1338 nanosatellites. They have a bright future ahead of them: an estimated 630 nanosatellites are to be launched on average each year in the near future1.

The origins of nanosatellites

Introduced as a design exercise at the Stanford University in 1999, the CubeSat format is one of the precursors of nanosatellites. It is the first standard space platform which made it possible to reuse systems between different missions. It allowed many companies to offer elements based on the plug-and-play model to rapidly develop new missions. In view of the proliferation of these satellites, rideshare launch services (to allow companies to share launchers) became widespread and many launch projects emerged. More than 140 micro-launchers are now in development to meet the increasing demand and eight of them are already operational2.

Scientists and engineers very quickly used these new low-cost platforms to develop missions of technology demonstration, like the GomX series (ESA and GomSpace), as well as scientific missions like AMICal Sat, UVSQSat and Eyesat to only mention French CubeSats launched in the past two years.

Their small size does not preclude commercial missions. This has not gone unnoticed by French companies which have sent into orbit satellites such as ANGELS to locate beacons (Hemeria, 2019), or the BRO satellites for electromagnetic intelligence (UnseenLabs, 2019 and 2020).

A powerful educational tool

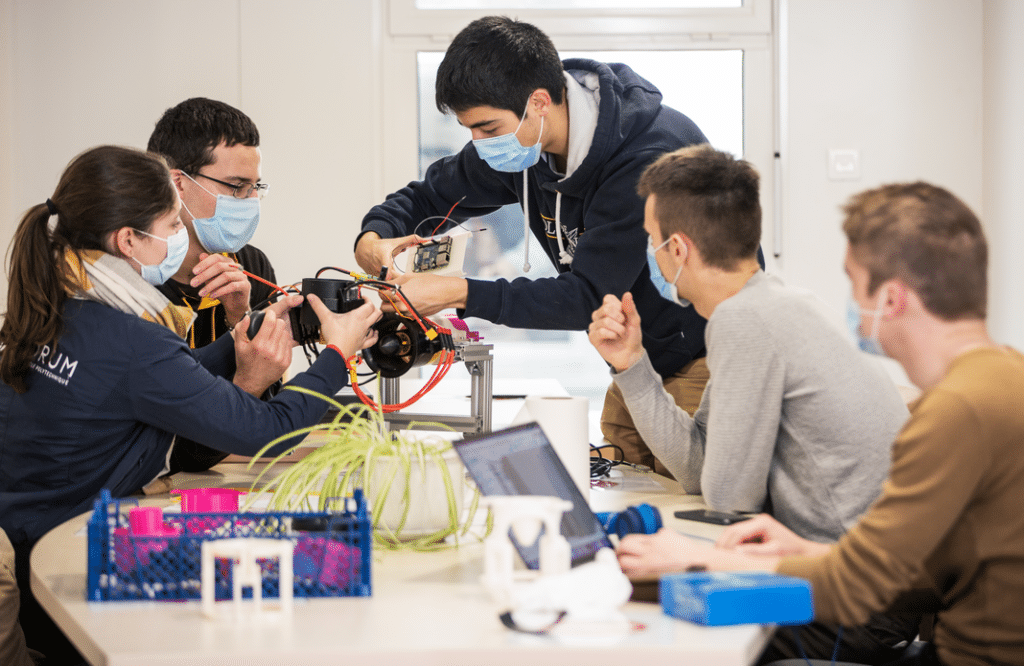

Their reduced cost usually makes nanosatellites a first-class educational tool. They answer a real need in higher education by making it possible for students to acquire concrete experience through student projects. Indeed, up until now, an engineer left his or her school with a wonderful theoretical background, but with no practical experience. This problem is even more important in the space sector because engineers, once they get a position, can spend years designing a space system without ever really seeing it.

Participating in a space project during studies thus represents a rich experience for students. All the more so since they work on various fields covering mechanical design and embarked data processing, as well as thermal analysis and flight mechanics, not to mention project management and teamwork. The experience is all the more rewarding because a nanosatellite remains a completely non-repairable autonomous system operating in a difficult, even hostile, environment: there is no second chance.

It is for these reasons that the École Polytechnique chose to mentor CubeSat student projects as early as 2011. The X‑CubeSat mission (member of the QB-50 mission launched in April 2017, and which ended in February 2019) involved more than 80 students from 7 different year groups. Following that operational and academic success, a second project, named IonSat3, was initiated by the Space Centre of the École Polytechnique in 2017, in collaboration with the ThrustMe start-up. The main mission of IonSat is keeping the nanosatellite in very low orbit thanks to an electric thruster. More than 50 students have already contributed to the preliminary design of this 6‑unit CubeSat (a volume of 30x20x10 cm). But these projects are also of interest for major stakeholders. Thus, IonSat is led in partnership with Thales Alenia Space, which is, in addition to ArianeGroup, a sponsor of the education program “Space: science and space-related challenges” of École polytechnique.

The new paradigm of constellations

The limited performance of these nanosatellites is offset by their use as satellite constellations (meaning in networks or swarms) in order to offer services which typical missions cannot achieve. The American company Planet thus launched more than 100 3‑unit CubeSats (30x10x10 cm) between 2013 and 2020 to observe all the Earth’s surface at least once a day. In 2020, 90 constellation projects were thus recorded4.

However, all the weaknesses of nanosatellites cannot be solved by launching them in great numbers. For example, there is a question of balance between the part of the satellite dedicated to the mission and the other functionalities, for instance to maintain orbit. For observation, resolution is proportional to sensor size, nanosatellites are thus limited in this respect. The format poses further limitations, especially with regard to communications: these are limited by the low agility and electrical capacity of the platform.

To face these challenges, some companies, like the Kineis company from Toulouse, produce slightly bigger satellites, but which are still small enough to belong to the “nanosatellite” category. Others, with a bigger market, have chosen to increase the performance of their satellites by taking advantage of the benefits of constellation without limiting their size to the nanosatellite format. That is why more ambitious mega-constellation projects, such as OneWeb and Starlink, focus on “SmallSats” (150 kg and 230 kg, respectively). With a big number of low-cost but powerful satellites, they have the best of both worlds.

A strong latent potential

Yet nanosatellites will not stay limited to low-cost or educational projects only. Indeed, the experience feedback from pioneer missions has shown their value in the context of scientific missions5. In addition to observing Earth, as previously mentioned, these CubeSats can be used in solar weather research thanks to mass spectrometers (SENSE in 2013) or X‑ray detectors (MinXSS in 2016); in astrophysics with the miniature telescope ASTERIA (2017) or the HaloSat mission (2018); in space exploration, as was the case for the MarCO CubeSats (Mars Cube One) which accompanied the Insight Probe to Mars in 2018, and the Lunar Flashlight which will accompany the Artemis I mission on the Moon in 2021. The applications of nanosatellites are thus limited only by our imagination!