For organisations, whether in the private or public sector, adapting to the future can seem like an impossible task. The challenge is to be agile and resilient in the face of a future that will be subject to change, and which often seems more worrying than desirable. Indeed, contemporary crises (climate, biodiversity, health, energy, access to resources) are exposing players and organisations to ever-greater tensions between, on the one hand, rapid and effective decisions rooted in the present and, on the other, the need to project into the future to avoid the solutions adopted turning into new dead-ends. The future thus appears to be a problematic temporal category for organisations: can we anticipate, guess at or predict the future? How can we think about a future that is a priori unknown and plural? Can the future be thought about and conceived within organisations? It is precisely to these questions that foresight approaches and practices attempt to provide some answers.

The emergence of foresight in France

The concept of “foresight” was developed by the French philosopher and senior civil servant Gaston Berger (1896–1960) in the 1950s. Before becoming a method or a discipline, for Gaston Berger, foresight was an attitude1, a state of mind that led to the preparation of action in the present based on reflection on possible or desirable futures. It is not a question of predicting the future, but of creating a dialogue between the present and the future to build a desirable outlook. The foresight approach is based on five principles:

- Seeing far ahead: thinking about the distant future (generally 10–50 years ahead) so as not to limit ourselves to the immediate consequences of current decisions.

- Thinking broadly: favouring multidisciplinary approaches to take account of the plurality of viewpoints and avoid reductionism.

- Think deep: identify the decisive factors so as not to succumb to extrapolation or analogy.

- Taking risks: agreeing to challenge received wisdom to gain greater freedom of thought.

- Thinking about people: paying attention to the role of people and the responsibility they bear.

Along with Gaston Berger, Bertrand de Jouvenel (1903–1987) was the other leading figure in the French school of foresight. In 1960, he founded the international association Futuribles (a contraction of “futures” and “possible”), which was initially funded by the Ford Foundation. For Jouvenel, foresight is not about making utopian projections. Foresight should be an “art” that enables realistic forecasts to be drawn up to support decision-making and the management of change.

The development of foresight in the USA

During the same period, foresight approaches also developed in the USA under the impetus of Herman Kahn, Theodore Gordon, and Olaf Helmer at the RAND Corporation. The RAND Corporation developed several formalised methods, the best known of which are the Delphi method and the scenario method2. Developed in the 1960s to deal with the uncertainty weighing on the development of weapons systems in a tense political and geopolitical context, the Delphi method involves gathering and comparing the opinions of experts on an identified problem. The aim is to reach a form of consensus through a series of iterative questionnaires, giving respondents the opportunity to revise and, if necessary, defend their judgement. The scenario method is an “imagination aid”3, the aim of which is to construct images of future situations based on the identification of a series of plausible and coherent events.

Initially, these tools were used in military or public policy contexts, but they were soon applied to the economic and social sphere, particularly within major groups such as Shell or General Electrics and international institutions (UN, UNESCO, UNITAR and the OECD, for example). The spread of French and American futures studies led to the creation of several structures, including the World Future Society in 1966, the Club of Rome in 1968 (which commissioned the famous Meadows report on the limits to growth)4, the Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies in 1969, the Swedish Secretariat for Futures Studies in 1971 and the World Futures Studies Federation in 1973.

Alternative futures in foresight

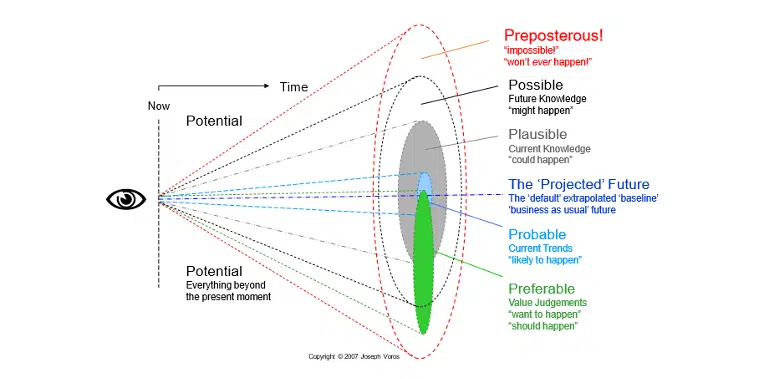

Foresight is concerned with different types of future (Figure 1)5: possible, plausible, probable, and desirable. Possible futures are distinct from absurd or impossible futures that do not respect the elementary laws of physics. Possible futures are, however, multiple, plural and may break with historical trajectories. They depend on future knowledge and characterise what could happen with a high degree of uncertainty. Plausible futures are likely futures that are consistent with the present situation. They remain uncertain but can occur given the current state of knowledge or considering known unknowns. Probable futures are a category of futures that are an extension of current trends. Finally, desirable or preferable futures characterise possible or plausible futures that are explicitly derived from value judgements. Since value systems differ greatly from one person to another and from one organisation to another, this category of future is highly dependent on the individuals involved in constructing it.

Foresight: methods and practices

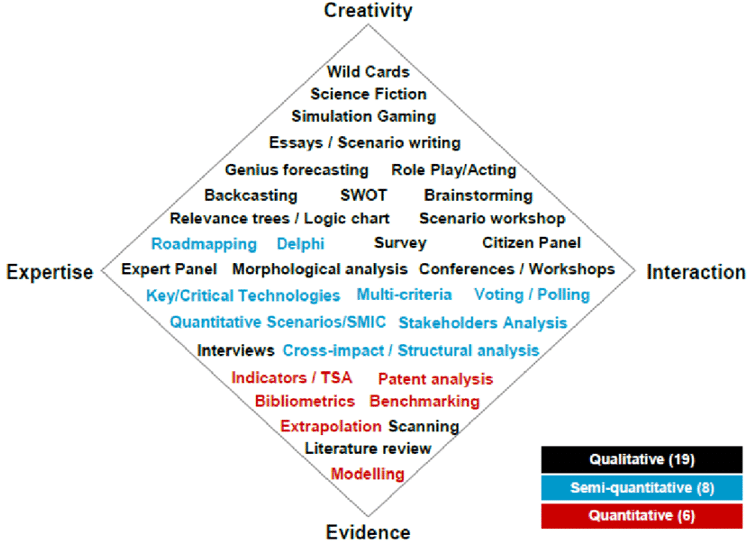

Far from being a general theory of the future, foresight has mainly developed through the gradual emergence of a multitude of heterogeneous methods and practices. The Foresight Diamond (figure 2) positions foresight methods according to four types of dimensions (creativity, interaction, expertise and evidence)6. These methods are not incompatible, but complementary, and their uses depend on the objectives and contexts in which they are used. They can be quantitative, qualitative, or even semi-quantitative. A single foresight exercise may involve between 5 and 6 different methods. The intermediate products of one method are often taken up at other stages of the scenario development process, producing important synergies and encouraging the integration of multiple perspectives7.

For example, benchmarking, patent analysis and bibliometric analysis of academic literature are quantitative approaches based on the use of data, information, and quantitative indicators. They aim to build up a state of the art on a particular issue or theme to be explored. Quantitative or semi-quantitative approaches can be described as predictive or exploratory. They are predictive when they are associated with forecasting or planning projects. They are exploratory when the aim is to identify interactions between different types of phenomena to uncover possible or plausible futures.

Qualitative approaches rely on imagination and creativity and tend to be normative in scope. The aim is to seek out and examine possible and desirable futures rather than probable ones. The results of this type of approach are then used to determine what actions need to be taken to make this desirable future a reality. For example, the backcasting method involves designing a desirable future and then imagining the various stages and decisions that would make it happen8.

Foresight differs from conventional forecasting and planning practices. It attaches particular importance to the process itself, during which areas of uncertainty are identified. These areas of uncertainty are then explored using foresight tools and methods, and it is during this exploration that participants build or acquire a shared vision of the future that supports them in their present decision-making. This shared vision of the future will then be used within the organisation to support knowledge creation, decision-making, strategic orientation and change management processe9.