BepiColombo mission: next stop, Mercury!

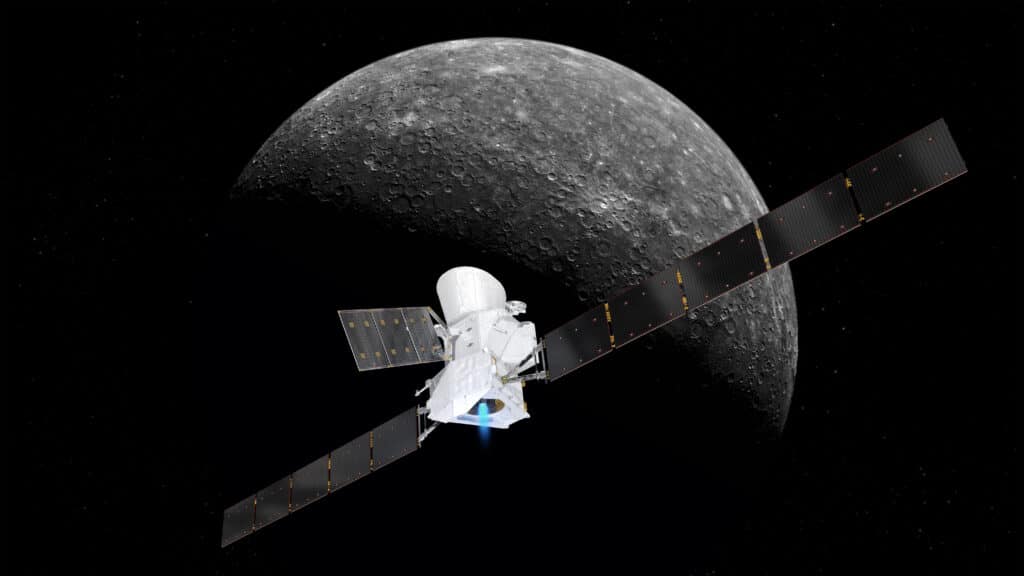

- The BepiColombo mission (2018-2028) is the third mission to explore the surface and environment of Mercury.

- BepiColombo aims to learn more about Mercury and its interactions with the Sun, to which it is so close.

- Because of the Sun’s attraction, this mission is a real space mechanics challenge: it therefore uses the gravitational assist technique.

- The Mass Spectrum Analyser (MSA) on board the spacecraft will measure Mercury's ionic composition.

- Studying Mercury will, among other things, confirm or deny the potential presence of water ice in its polar craters.

Mercury, one of the four telluric planets in our Solar System, is the smallest planet, the closest to the Sun, and the only one, along with the Earth, with a magnetic field. Yet, because of its proximity to the Sun and its speed, Mercury is also the least studied of all the planets.

After the two American NASA probes, MARINER 10 (1973–1975) and MESSENGER (2004–2015), the BepiColombo mission is the third mission to explore the surface and environment of Mercury. BepiColombo will shed new light on the structure and internal dynamics of the planet, how its magnetic field is generated and how it interacts with the Sun and the solar wind. Through comparative studies, the mission will also improve our understanding of our planet, for example, the coupling between the terrestrial environment and the interplanetary medium.

BepiColombo is named after the Italian mathematician and engineer Giuseppe (Bepi) Colombo (1920–1984). He played a major role in the success of the MARINER 10 mission, the first mission to Mercury, with his orbital mechanics calculations for the determination of the first gravitational assist by a spacecraft.

BepiColombo also aims to probe the characteristics and chemical composition of Mercury’s surface, as well as the presence of water ice in the polar craters, which are perpetually in shadow. Indeed, due to the extremely low tilt of the planet’s rotation axis, the meteorite crater floors at the poles receive no direct sunlight. Ultimately, BepiColombo’s observations will help us better understand how our solar system formed and how planets near their parent stars evolve.

BepiColombo, the first-ever mission

BepiColombo is the first European mission to Mercury. It was developed by the European Space Agency (ESA) together with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). It is also the first planetary mission with two orbiters (not including Earth-orbiting satellites): the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO), under the responsibility of ESA, is a three-axis stabilised satellite that will orbit near Mercury and study the surface, geological composition, and exosphere (thin atmosphere) of the planet. The Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO), renamed ‘Mio’ under the responsibility of JAXA, is rotating and will orbit at a greater distance in Mercury’s magnetosphere – the region of space around the planet that is dominated by its magnetic field.

Mio will make in situ measurements of the magnetic field, electric field, and particles (ions and electrons) in the hermetic environment, but also in the inner heliosphere. The different positions of the two orbiters will allow for the first time to make observations from two distinct angles and to follow both spatially and temporally the coupling between the solar wind and Mercury’s magnetosphere, the exchanges between the magnetosphere and its exosphere, and the transport processes.

When it arrives near Mercury, BepiColombo will be subjected to such an intense radiative environment that the satellite will experience temperatures of over 350°C.

BepiColombo carries two other modules: the Mercury Transfer Module (MTM), which uses the solar-electric propulsion technology needed for Earth-Mercury travel, and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter’s Sunshield and Interface Structure (MOSIF), which is installed on top of the probe to protect Mio from heat flux and infrared radiation during the cruise phase. When it arrives near Mercury, BepiColombo will be subjected to such an intense radiative environment that the satellite will experience temperatures of over 350°C – high enough to melt any of the probe’s components or instruments. To protect against these temperatures, a thermal control system has been specially designed for the mission to ensure that the materials can withstand the very intense ultraviolet radiation and the flow of charged particles from the solar wind without degradation.

A real space mechanics challenge

The BepiColombo mission was launched in October 2018 from Kourou in French Guiana and will be inserted into orbit around Mercury in December 2025. “This insertion is extremely difficult because the planet is close to the Sun and the spacecraft risks being ‘sucked in’ by its gravitational pull. The challenge is not to go there, but rather to aim at Mercury,” explains Lina Hadid, CNRS research fellow at the Plasma Physics Laboratory (LPP1). In fact, the spacecraft must be slowed down considerably in the inner heliosphere to prevent it from being attracted by the Sun. This is a real space mechanics challenge!

Despite its innovative and efficient ion-electric propulsion, it is almost impossible for a multi-ton mission to reach orbit around Mercury by braking alone. “To overcome this problem, BepiColombo performs several flybys of other planets to modify its trajectory: this is the principle of gravitational assistance and is the reason why BepiColombo’s cruise phase is very long,” adds Lina Hadid. “During this cruise phase, the probe benefits from nine ‘boosts’ provided by three planets: Earth (1x), Venus (2x) and Mercury (6x). Each flyby allows BepiColombo to tighten its trajectory, which will eventually merge with that of Mercury in December 2025.”

BepiColombo flew past Mercury for the first time in October 2021 and for the second time in June 2022, passing within 200 km of its surface (an altitude never reached by either MARINER 10 or MESSENGER). In doing so, its cameras photographed the cratered surface of the planet. Since its departure, the probe has also flown past the Earth once in April 2020, and Venus twice, in October 2020 and August 2021.

In search of the ionic composition

“During BepiColombo’s long cruise, not all the instruments are switched on, so we can’t make as many measurements as we’d like. So, we can’t make as many measurements as we would like,” says Lina Hadid. “However, among those that are operational during the flybys is an ion mass spectrometer on board Mio called Mass Spectrum Analyser (MSA), which we have developed at LPP and in which I am involved.” This spectrometer will measure the ion composition (charged particles) around Mercury. Although the FIPS instrument on board MESSENGER has done this before, it has not been able to identify heavy ions (typically, oxygen and beyond) with high mass accuracy. In addition, the field of view of this instrument was very limited.

“The MSA spectrometer will allow us to identify different ionic species such as magnesium (Mg+, atomic mass M = 24 u), silicon (Si+, 28 u), molecular oxygen (O2+, 32 u), potassium (K+, 39 u) or calcium (Ca+, 40 u) with a mass resolution unmatched on a space mission. Another instrument in which the LPP participated on board Mio is the Dual Band Magnetic Fluxmeter (DBSC) dedicated to the measurement of high frequency magnetic fields (100 mHz-640 kHz).”

The first flybys of Venus and Mercury allowed us to correct some problems with the onboard software.

The cruise phase is also an important time to check that all the instruments on board both orbiters are working properly. “It is very important for us to properly calibrate the instruments in space to make sure they work as expected! For example, for MSA, the first Venus and Mercury flybys allowed us to correct some problems with the onboard software, so we were looking forward to seeing the measurements during the second Mercury flyby in June 2022! And indeed, during this second flyby, MSA revealed the presence of energetic planetary protons and helium (He+). We also observed heavy ions, but at a lower density than previously detected by MESSENGER. We are currently analysing these data to better understand the source of these ions. At the same time, we are looking forward to the next Mercury flyby in June 2023!”

Finally, BepiColombo may even be able to confirm – or disprove – the presence of icy water on Mercury, a subject that has been intensely debated for many years. In the 1990s, researchers discovered, thanks to the Arecibo radio telescope, that there are regions in the north of the planet, at high latitudes, that exhibit abnormally high light reflectivity. Using its onboard cameras, the MESSENGER mission observed that these areas coincide with the presence of impact craters on the surface of Mercury. Since the planet’s rotation axis is practically uninclined (unlike Earth’s), these craters are perpetually in shadow.

“The high reflectivity could therefore be due to the presence of icy water at the bottom of these craters – a surprising conclusion given that Mercury is so close to the Sun and so hot,” explains Lina Hadid. “If this result is confirmed, the Sun’s rays would never have reached this water ice, which formed billions of years ago and would therefore never have melted!”

Interview by Isabelle Dumé

Key dates of the mission

- 20 October 2018 (01:45:28 UT): Launch from the Guiana Space Centre

- 13 April 2020: Earth flyby

- 16 Oct 2020: Venus flyby

- 11 Aug 2020: Venus flyby

- Oct. 1, 2021: First flyby of Mercury

- June 23, 2022: Mercury flyby

- June 20, 2023: Mercury flyby

- September 5, 2024: Mercury flyby

- December 2, 2024: Mercury flyby

- Jan 9, 2025: Mercury flyby

- Dec. 5, 2025: Insertion into Mercury orbit

- May 1, 2027: End of nominal mission phase

- May 1, 2028: End of mission extension

References