BepiColombo: revelations from the Mercury mission

- The BepiColombo space mission will arrive on Mercury, the smallest planet in our solar system and the closest to the Sun, in 2026.

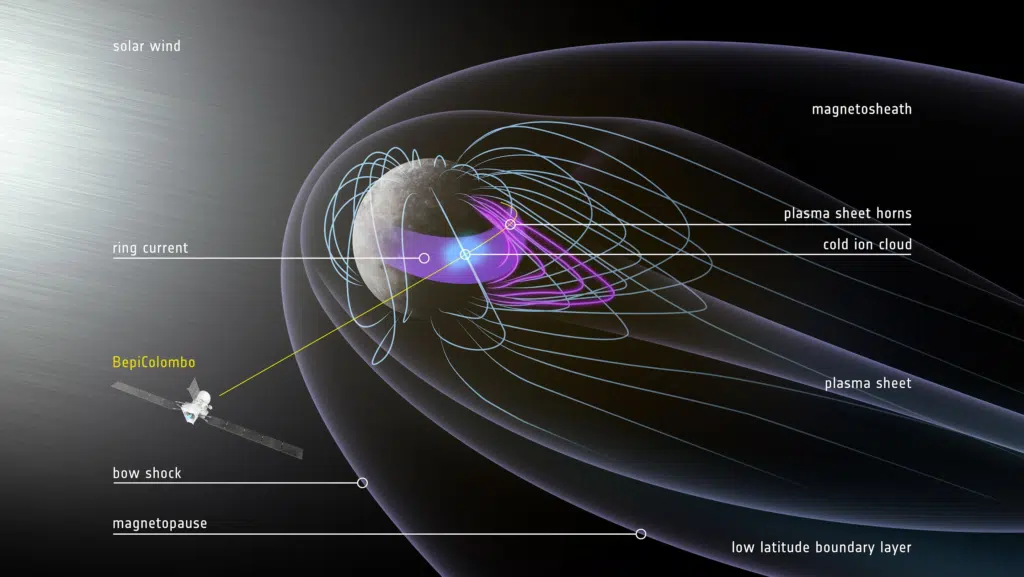

- The existence of a magnetic field around Mercury is surprising: although weak, it is powerful enough to deflect the solar winds.

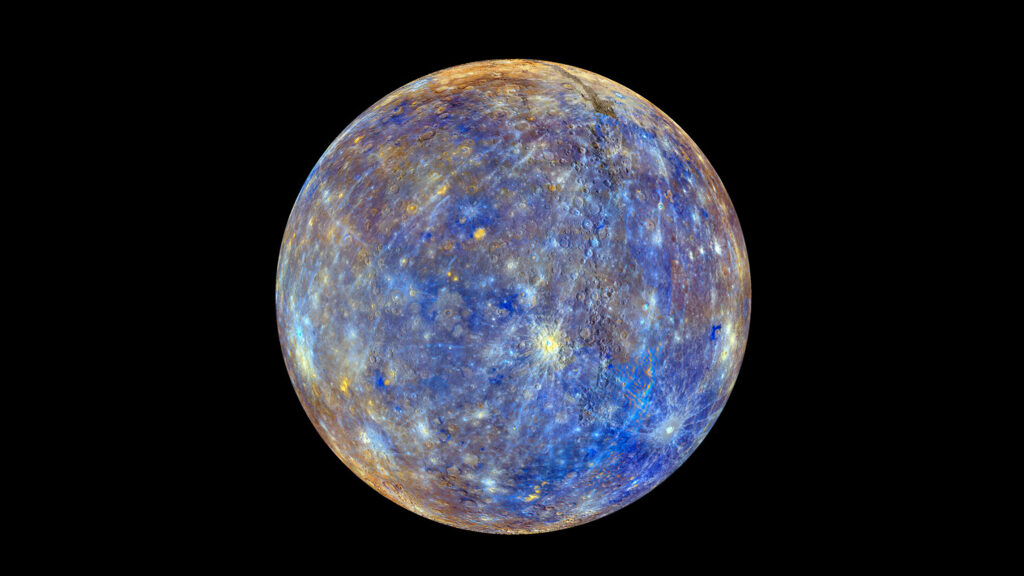

- MESSENGER 3 has greatly advanced research on Mercury but has so far mapped only 45% of its surface.

- The 3rd flyby of Mercury by BepiColombo has made it possible to characterise the nature of the particles present in the magnetosphere and their mode of displacement.

- This flyby also revealed new information that will help us better understand the interaction between the solar wind and the magnetospheres of planets.

In 2026, the BepiColombo1 space mission will arrive at its destination: Mercury, the smallest planet in our solar system and the closest neighbour of the Sun. During its 7.9‑billion-kilometre journey, it will pass close to the planet several times to adjust its speed and trajectory so that it is “trapped” in its orbit when the time comes.

Mercury’s intrinsic magnetic field is weak, with a dipole strength nearly 100 times less than that of the Earth. However, the existence of a magnetic field, even a weak one, on Mercury is surprising in itself. It is nevertheless powerful enough to deflect the solar wind – a stream of particles, mainly electrons and protons, ejected from the Sun’s upper atmosphere (in other words, its corona). This “shield”, or magnetosphere, is similar to the Earth’s magnetosphere. The difference is that the fundamental processes that release plasma and energy occur much more rapidly in Mercury’s magnetosphere.

Mercury has already been flown over several times. The first mission, Mariner 102, made three flybys and discovered traces of heavy atoms near its exosphere – a thin atmosphere composed of atoms and molecules that have been expelled from the planet’s surface. Later, land-based telescopes remotely detected a selection of ions, including sodium (Na+), potassium (K+) and calcium (Ca+), which probably also come from the planet itself.

But it was the MESSENGER mission3 that really changed our view of Mercury. In particular, it provided a great deal of important information about the ionised plasma in its magnetosphere. This plasma is a hot ionised gas containing hydrogen and helium (II) (He2+) ions from the solar wind and heavier species such as He+, O+ and Na+. However, MESSENGER has mapped only 45% of the planet’s surface and has therefore left many questions unanswered. In particular, how the planet’s magnetosphere interacts with the solar wind.

Sampling of particles from the magnetosphere

Researchers are now presenting the results of BepiColombo’s third flyby of Mercury, which took place on 19th June 2023, and in particular the results from the MPPE (Mercury Plasma Particle Experiment) instrument suite. These were active on the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (Mio), an instrument led by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). Mio is one of two scientific orbiters that will be captured in Mercury’s orbit in 2026, the other being the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO), led by the European Space Agency (ESA). Together, these two spacecraft will provide a complete picture of the environment around Mercury.

These flybys are very fast, taking about half an hour (terrestrial) to cross Mercury’s magnetosphere, passing from dusk on the planet to dawn. During the third flyby, the spacecraft was able to get as close as 235 km above Mercury’s cratered surface. During this flyby, Mio characterised the nature of the particles present in the magnetosphere and the way in which they move. “These measurements allow us to clearly trace the magnetospheric landscape during the brief gravitational assist,” explains Lina Hadid, who is currently a research fellow at the CNRS and works at the Plasma Physics Laboratory (LPP) at the École polytechnique (IP Paris). Lina Hadid is the scientific manager of one of the instruments of the MPPE consortium, the ion mass spectrometer, whose optical part was developed at the LPP. She and her colleagues have published their latest results in Nature Communications Physics.

The researchers claim to have observed ‘boundaries’ such as the ‘shock wave’ separating the solar wind and Mercury’s magnetosphere, as well as other regions such as the plasma sheet, which is a more energetic and denser region of ions located at the centre of the magnetic tail. “These two results were nevertheless expected,” explains Lina Hadid.

Discovering new surprises on Mercury

“However, there have been plenty of new surprises,” she adds. For example, a layer at low latitudes, defined by a region of turbulent plasma at the edge of the magnetosphere. This layer contains particles with an energy range of up to 40 keV/e, much broader than those ever observed before on Mercury.

Another important result is the observation of energetic hot hydrogen ions (H+) trapped at low latitude and near the equatorial plane of Mercury, with energies of around 20 keV/e and at low latitude. According to Lina Hadid and her colleagues, this result can only be explained by the presence of an annular current (an electric current carried by charged particles trapped in the magnetosphere), but further observations and analyses will be necessary to confirm or deny this. If confirmed, this ring current will be similar to that of the Earth, which is tens of thousands of kilometres from its surface and which, for its part, is well understood.

Finally, Mio also detected “cold” plasma ions of oxygen and sodium with signatures of the presence of potassium with an energy of less than 50 eV/e when it moved through the planet’s nocturnal shadow. These ions come from the planet itself and were probably ejected when micrometeorites hit its surface or during interactions with the solar wind.

According to the researchers, these new results will provide a better understanding of how the solar wind interacts with the magnetospheres of planets in general. On Earth, it is important to understand this phenomenon because the charged particles in the solar wind disrupt our planet’s magnetosphere when they collide with it. These disturbances, known as “space weather”, can damage satellites, affect communication technologies and GPS signals, and even cause power outages on the ground or at altitude.

BepiColombo successfully completed its fourth flyby in September 2024 and came as close as possible to the planet, about 165 km from its surface. On this occasion, it captured the best images of some of the largest impact craters on Mercury. It made a fifth and sixth flyby of the planet, on 1st December and 8 January 2025 respectively. The mission is scheduled to last until 2029…