A (very) brief history of infinity

- Infinity is a mathematical concept originating from Zeno of Elia (~450 BC) who tried to show its “physical” impossibility. This resulted in the “arrow paradox”, but which was solved later on.

- Many mathematicians and physicists went on to try understanding infinity and to explain it by various theories and experiments.

- Georg Cantor went further than anyone else by asking a simple question: can we compare two sets of infinite numbers? Can one be “bigger” than the other?

- His method consists of pairing an element of the first set with an element of the second. If each element finds its partner and none remains alone (this is called a bijection), then we can say that the two sets are equal.

- The Von Koch flake is constructed by adding a triangle on each edge of the previous figure and has an infinite perimeter.

Once considered as a sacred concept (only God is infinite) or a metaphysical one (the human mind will never be able to entirely conceive it), infinity has since entered the domain of science and technology. Today, we measure it, compare it, study it, and use it almost like a normal number.

But what is infinity? And how did we learn to tame it?

An old story

It seems that questions about infinity are almost as old as humanity. Unfortunately, the writings that attest to this are all the rarer because they are old. We know that the philosophers of the first millennium B.C. were already wondering about the amazing properties of infinity.

But is infinity only a concept? A weird idea that mathematicians play with? Or does it have a connection with the world around us? Is anything really infinite?

For Anaximander, infinity is the founding principle of reality. From it are born an infinite number of worlds that fill the volume of the Universe. For Heraclitus, on the other hand, it is time that is infinite. It has always been and will always be. It is through infinity that we perceive our own existence.

Of course, none of these statements are supported by an “experiment” or a “measurement” by current scientific standards. It is more a philosophical position that differentiates one school of thought from another.

From mathematics to physics

Of course, infinity is first and foremost a mathematical concept. And it is mathematicians who took it upon themselves to observe it a little closer. Zeno of Elia (~450 BC) tried to show the “physical” impossibility of infinity, not by measuring it but by using it to divide things into smaller and smaller elements.

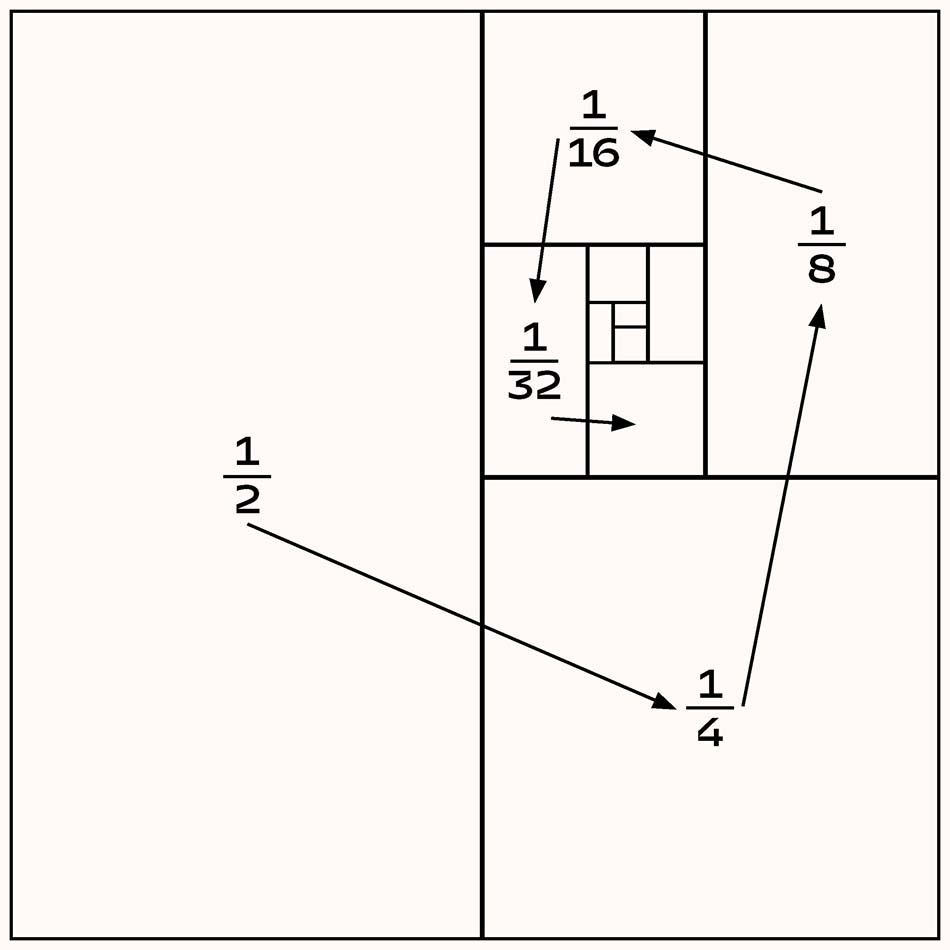

The result is his famous “arrow paradox” that, according to him, should never be able to hit its target. Indeed, one can always divide its remaining path by two and there will always remain a portion of path to cover (1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, 1/32), ad infinitum.

Since it takes an infinite number of steps to cross the distance between the bow and the target, Zeno concluded that it was impossible for the arrow to reach its destination in a finite time.

However, this paradox was solved much later by one of the branches of mathematics that studies infinite sums of numbers: the series.

Adding 1/2+ 1/4+ 1/8+ 1/16+… is like adding 1/2+ 1/22+ 1/23+ 1/24+…

This series is called a geometric series. It is written in the form:

Its resolution is very simple. When n tends to infinity, the value of this sum tends naturally to 1.

A schematic resolution is even simpler. In the figure below, we can intuitively see that, to fill a square with side 1, we must add the elements whose area corresponds exactly to the series above it.

What Zeno was missing was the counterintuitive result that the sum of an infinite number of numbers does not always give an infinite result.

In other words, it is not because the trajectory of the arrow can be decomposed into an infinite number that the time it will take to cover them will be infinite. Paradox solved. The arrows can now reach their target with complete peace of mind.

Later, Isaac Newton perfected the art of measuring arbitrarily small values by developing infinitesimal calculus. This led to the famous derivatives (and integers) which mathematics, but also modern physics, could not do without today to describe and understand the world.

Comparing infinities

There is no need to understand or visualise infinity to use it. In the end, infinity is just a tool among many others that mathematics puts at our disposal to measure, calculate and understand our environment.

But a German mathematician from the end of the 19th Century went much further than anyone else at the time to manipulate infinity, or more precisely infinite sets.

Georg Cantor asked himself a simple question: can we compare two infinite sets? Can one be “bigger” than the other?

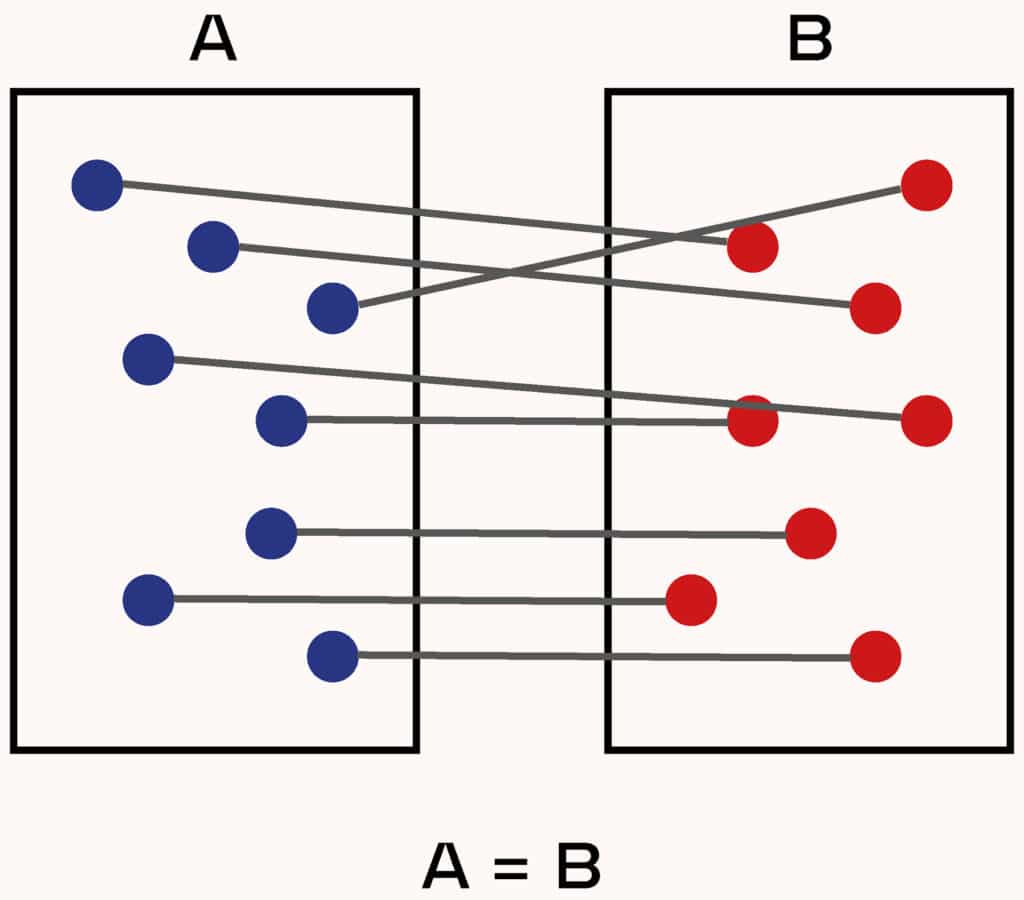

His answer lies in the way he compares two sets: instead of counting the number of elements of the latter and comparing them (which cannot be done with an infinite set), the method consists in trying to match an element of the first set with an element of the second. If each element finds its partner and none remains alone (we call this a bijection), we can then say that the two sets are equal. And this method applies to both finite and infinite sets.

This is how we can prove that the size of the (infinite) set of positive integers is strictly equal to that of the set of integers (positive and negative).

What’s more, we can also show that, although there are infinitely many fractions between two integers, the size of the set of integers is strictly equal to the size of the set of numbers that are written as fractions. However, it has also been proven that the set of real numbers (all numbers written with a decimal point and a finite or infinite number of decimal places) is strictly larger than the set of integers.

As counter-intuitive as it may seem, two different infinities can have the same size, but, conversely, not all infinities are equal.

Impossible geometries

Can we draw figures with infinite parameters?

Besides the circle (which can be considered as a polygon with an infinite number of sides), other strange figures started to emerge during the second half of the 20th Century: fractals.

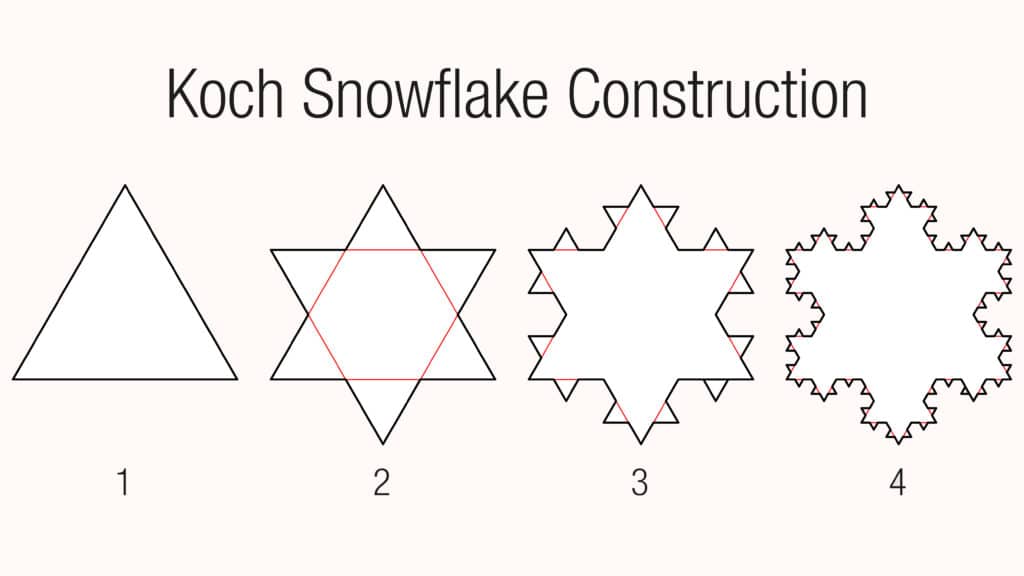

One way to create them is to build them by iteration, step by step. After an infinite number of steps, the figure is finished, and we can study its properties. The Von Koch flake, for example, is an extraordinary figure: although its surface is finite, its perimeter is infinite.

This kind of geometry has been successfully applied in the field of telecommunications. Since the end of the 80’s, fractal antennas have been developed, whose length, if not infinite, is very large, but whose volume remains small, which allows to obtain compact and efficient systems.