You co-founded ThrustMe in 2017 with Dmytro Rafalskyi. What issues did you seek to resolve?

Ane Aanesland. Our aim is to ensure that the space industry, which is undergoing major changes, becomes economically and environmentally sustainable. To that end, we want to control satellites better. We want to make sure that they can remain in position as long as possible by avoiding collisions and improving their movements in orbit, as well as their service life.

The multiplication of constellations raises several issues. To keep their cost affordable, many micro- and nanosatellites do not have engines, and therefore, are not autonomous. They are placed in low orbit, between 350 and 700 km, and at these altitudes one of two things will happen. Either they gradually undergo friction which modifies their orbit, progressively makes them descend and brings them into the atmosphere where they burn; or they remain in orbit, where they die.

The lifespan of a satellite varies exponentially depending on the distance of their orbit: 7 months at 300 km, more than 30 years at 700 km, and probably 100 years at 1 000 km. Thus, satellites would have to be equipped with a propulsion system in order to increase their lifespan in low altitudes and to descend those in high altitudes at the end of their service life. The problem is that in the current situation, propulsion systems considerably increase the cost and complexity of satellites. The ambition of ThrustMe is to solve this issue.

What solution did you come up with to reconcile economic and environmental challenges?

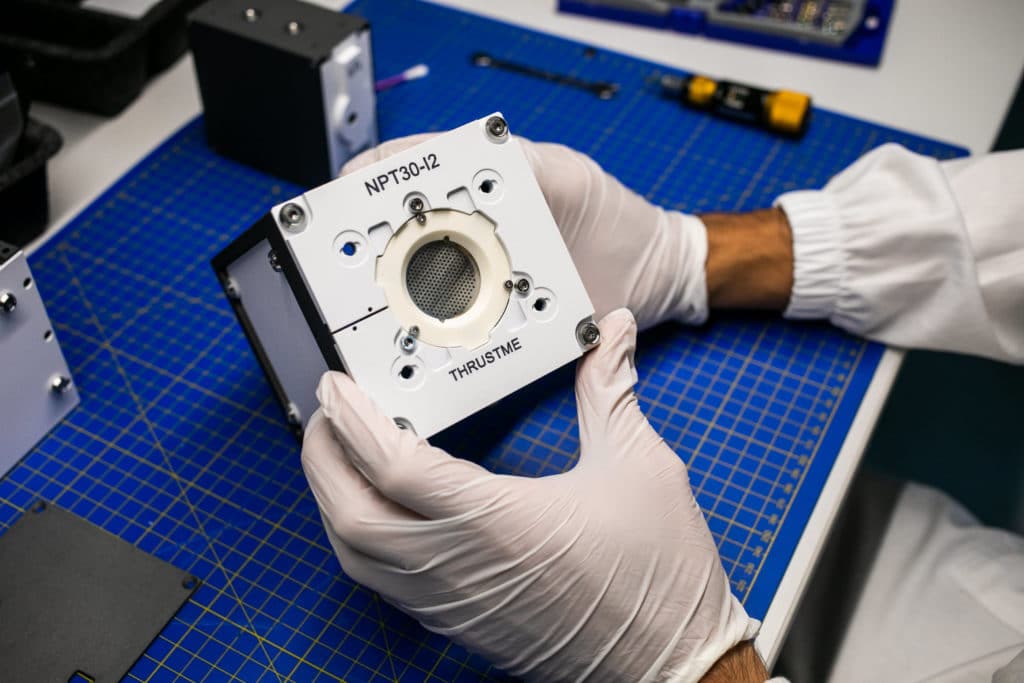

We developed a complete propulsion system, which integrates the thruster, electronics and fuel. It is an electric thruster with solid iodine developed for mini-satellites that weigh 10–100 kg/m. Three of these systems were placed in orbit at the end of 2019 and in 2020 by the Chinese company Spacety. Each were very different: the first was a 6‑unit CubeSat (approximately 12 kg), the second was a microsatellite weighing around 50 kg, and the third a small satellite of 180 kg. We tested the different features of our propulsion systems, and the results were extraordinary.

How is your propulsion technology different from those that already exist?

Currently, there are two types of propulsion: chemical or electric. The electric system is relatively new and only 20% of very big satellites are equipped with that. It is more efficient and easier to miniaturise than chemical propulsion, which makes it perfect for micro- and nanosatellites.

We chose iodine as the propellant (the “fuel” of the thruster), because it is possible to store it in solid form, and it only requires little heat to be sublimated into gas. In contrast, xenon, used by most current electric propulsion systems, must be stored under high pressure. Xenon is also a rare gas and in 5 to 10 years, the demand will be twice as high as the production capacity.

Furthermore, for a constellation of 800 to 1000 satellites, the cost of xenon is around €40M. SpaceX opted for krypton, which allowed them to divide by 3 the cost of the propellant. But iodine divides this cost by 40. In other words, only €1M are needed to propel an entire constellation. It’s a real revolution! We also demonstrated in laboratory conditions and directly in space that iodine is more efficient than xenon at equal power. This makes it possible to keep the satellite in the right orbit or deorbit it.

Do you have competitors on this technology?

In the years 2015–2018, several start-ups got involved in propulsion, because there was a real lack of solutions on this area. So, yes, there is competition. Even the NASA tried to develop a solution with manufacturers, but iodine is not an easy subject. It is corrosive. You need to know chemistry, materials science and so on. We developed a solution to transform iodine into gas then into plasma which, in addition to its originality, also makes it possible to reduce the weight and cost of the propulsion system. It is not only the work of engineers. And herein lies the strength of ThrustMe.

Could you be more specific?

We are a young and very small company compared to our competition. We only have 17 permanent staff and a few interns. But when deeptech companies develop a product, they first run a proof of concept (PoC) and then see how to manufacture the product. In our case, we considered the manufacturing of our propulsion system from the very beginning. Of course, we have scientists, but we also have aerospace engineers, engineers in electronics, etc. It was very important for us to hire engineers along with our scientists at the start of the company. We wanted to contribute to the space revolution which is currently under way. We want to change things and make the space industry more sustainable.

What is next for ThrustMe?

At the beginning of 2020, we signed a first contract with the European Space Agency (ESA), related to the ARTES program (Advanced Research in Telecommunications Systems). It aims to solve the emerging space-related challenges associated with the rise of satellite constellations. We are also making several systems designed to equip a constellation for Earth observation for a client.

Moreover, we are conducting a mission with the space agency of Norway on a satellite which will be launched at the beginning of 2022. The aim is to demonstrate collision avoidance with our electric low-thrust thruster, the NPT30. It is the first mission of this kind on a commercial satellite with an on-board high-precision GPS system.

Finally, we are also participating in a scientific project of the INSPIRE program (International Satellite Program in Research and Education) with several universities to study the upper ionosphere, from 300 to 1000 km. The aim is to control the descent of a satellite to 300 km and to maintain it at this altitude to study climate change.